Ah, summer – vacations (pre-COVID), swimming pools (pre-COVID), ice cream, vegetable gardens, and, in many places, really high temperatures. These things all go hand-in-hand (or at least they did before the pandemic). Many gardeners feel that the heat of mid-summer goes hand in hand with garden production; those high temps driving production on those fruiting plants like tomatoes and peppers. But…..could they be wrong?

We’ve had lots of extra hot days this summer in Nebraska, so it stands to reason that we should have really great production on those garden favorites like tomatoes, right? Then tell me why our extension office has received numerous questions this year about why tomatoes aren’t setting on or ripening. Heck, we even had a Facebook post about tomatoes not ripening in the heat go viral (well, for our standards – 300,000 views/2,000 shares). Could it be a disease? Nope – it’s the heat. High daytime temperatures can have a big effect, but the effects are compounded when nighttime temperatures are high as well.

It turns out that high heat does two things in many of those fruiting vegetables (and of course fruits) that we grow. First, it inhibits pollen production, which in turns reduces fruit set. Second, heat inhibits gene expression for proteins that aid in ripening/maturation of the fruit. Heat stress also reduces photosynthesis (Sharkey, 2005) in many different plants, which would slow down plant processes (such as fruit development and ripening) as it reduces the availability of sugars to fuel these processes. So high heat can not only reduce the number of fruits developing on the plant, but also slow down the ripening process for fruits that have already set. And if you think that these effects only happen at super extreme temps, most of the research studying temperature effects of this nature use a common “high ambient temperature” of 32°C/26°C for daytime/nighttime temperatures. For us U.S. Fahrenheit-ers, that’s 89.6°F/78.8°F, which isn’t really all that hot for most of us.

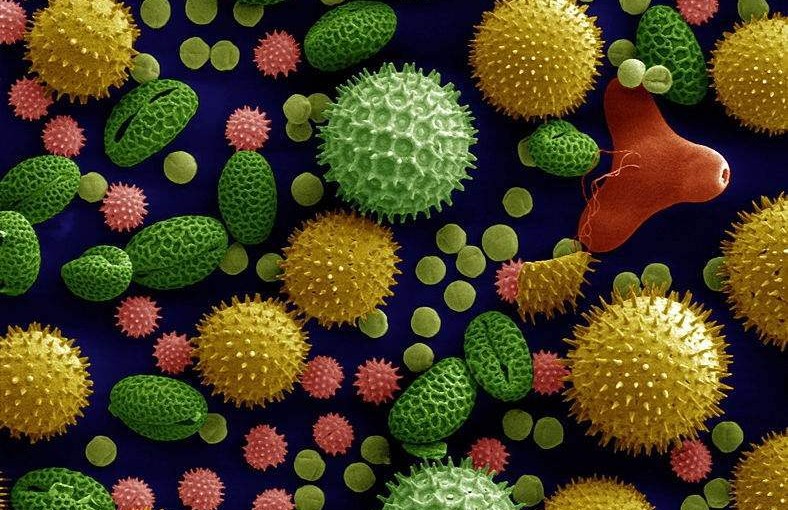

Many studies show that application of this “high ambient temperature” to crops such as tomatoes, beans, and corn during the pre-fertilization phases of reproduction (ie – flower/pollen development) can negatively effect fruit set. The introduction of Porch and Jahn (2001) gives a pretty good overview of literature detailing the effect in beans (Phaseolus vulgaris). I’ll sum it up here: heat stress while the pollen is forming (called sporogenesis) led to pollen sterility and failure of pollen to release from the anthers (dehiscence). It also led to flower abscission (basically the plant aborts the flower) and reduce pollen tube formation (how the pollen nucleus gets through the stigma to the ovule for pollination) when applied during the period of pollen sac and ovary development. And application during flower opening (anthesis) resulted in pollen injury (sterility) and reproductive organ abscission. All of these effects lead to reduced fruit/seed set in beans. (Interestingly, heat stress at the ovary development phase also led to parthenocarpy – basically the pods developed, sans seeds, without fertilization).

However, we get the most calls about tomatoes (they’re the top crop for most home gardeners). Is it the same issue? Yep. Numerous studies (Sato, et al., 2000; Pressman, et al., 2002; Abdul-BAki, 1992) show the same effect in tomatoes. Pressman, et al. (2002) linked the effects on pollen to changes in carbohydrates in the anthers (reduced starch storage and carbohydrate metabolism).

To add insult to injury, high temperatures also slow down or stop ripening of crops like tomatoes. Picton and Grierson (1988) found that 35°C (95°F) temperatures altered the gene expression in tomato fruits – inhibiting the expression of polygalacturonase, which softens cells walls, allowing the fruit to ripen. Reduced photosynthesis would also reduce the availability of sugars for fruit development and ripening.

But there’s hope, both this season and in the long term! The effect on the plants is not permanent. When temperatures drop below that “high ambient temperature” threshold pollen production, and therefore fruit set, will return to normal (as long as the plant is healthy). Sato, et al. (2000) found that pollen release and fruit set resumed within a few days after heat stressed plants were “relieved” and temperatures dropped back into the optimal range of 26-28°C/22°C (78.8-82.4°F/71.6°F). So many of those plants will become productive again (good news for my own tomatoes and beans, which had an initial flurry of production then went on vacation), especially as we head into fall. And efforts are under way to develop and test heat stress resistant cultivars.

This last point may be more important than you realized. These production problems plague many areas around he world at current climactic norms. Many fear that increasing temperatures will limit the productive capacity of many areas of the world that are already struggling. It is easy to see how the difference in just of just a few degrees can take your veggie production from prolific to paltry.

You can also try to reduce the heat a bit yourself for an immediate fix. Shade cloth can help reduce temperatures a little bit, which may make all the difference in your garden if you’re just slightly over the “high ambient temperature” threshold.

But in the meantime, if your vegetable garden has taken a summer siesta it will get around to producing again one day. You’ll just have to take good care of the plants in the meantime. And perhaps it’s a blessing in disguise – when its that hot I don’t want to be out working in the garden much, either.

Sources

- Abdul-Baki, A. A. (1992). Determination of pollen viability in tomatoes. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science, 117(3), 473-476.Porch, T.G. and Jahn, M. (2001), Effects of high‐temperature stress on microsporogenesis in heat‐sensitive and heat‐tolerant genotypes of Phaseolus vulgaris . Plant, Cell & Environment, 24: 723-731. doi:10.1046/j.1365-3040.2001.00716.x

- Pressman, E., Peet, M. M., & Pharr, D. M. (2002). The effect of heat stress on tomato pollen characteristics is associated with changes in carbohydrate concentration in the developing anthers. Annals of Botany, 90(5), 631-636.

- Sato, S., Peet, M. M., & Thomas, J. F. (2000). Physiological factors limit fruit set of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) under chronic, mild heat stress. Plant, Cell & Environment, 23(7), 719-726.

- Sharkey, T. D. (2005). Effects of moderate heat stress on photosynthesis: importance of thylakoid reactions, rubisco deactivation, reactive oxygen species, and thermotolerance provided by isoprene. Plant, Cell & Environment, 28(3), 269-277.