For years I subscribed to Consumer Reports. I appreciated their objective approach to product testing and lack of advertising. In their own words, their policy is to “maintain our independence and impartiality… [so that] CU has no agenda other than the interests of consumers.” But recently they’ve veered off the science-based trail – at least the one running through our gardens. Their approach to plant and soil sciences is more pseudo than science. And last year, after 30+ years of loyal membership, I quit my subscription when Consumer Reports began partnering with Dr. Oz (see here for instance ).

So until today I’ve been blissfully unaware of whatever CR has published on gardening and garden products. Then this post appeared on our Garden Professors blog group page ). I’ve included some of the article below along with my italicized comments in brackets.

“Lawn care without the chemicals: rid your yard of weeds and pests with these mostly organic solutions”

“…Here are 10 common weeds and pests that plague homeowners nationwide, along with chemical-free measures [“chemical-free?” Well, we shall see.] that should be effective in bringing them under control. For more information, go to the websites of Beyond Pesticides and the Great Healthy Yard Project. [Neither of these two sites is remotely scientific or objective.]

“Dandelion – what is it? A perennial weed whose common yellow flowers turn to windblown seed. Telltale signs. Though a handful of dandelions is no big deal, a lawn that’s ablaze in yellow has underlying problems that need to be addressed. How to treat. Like many broadleaf weeds, dandelions prefer compacted soil, so going over the lawn with a core aerator (available for rent at home centers) might eradicate them. [Like many broadleaf weeds, dandelions will grow anywhere. That’s why they’re called weeds.] It also helps to correct soil imbalances, especially low calcium.” [I’m curious how CR determined a “soil imbalance.” And did they test their hypothesis experimentally?]

Dandelions obviously suffering in a calcium rich soil

“Barberry – what is it? An invasive shrub with green leaves and yellow flowers, often found in yards near wooded areas. Telltale signs. Left unchecked, the shrub’s dense thickets will start to choke off native trees and plants. How to treat. Cut back the stems and paint their tips with horticultural vinegar or clove oil (repeated -applications may be needed). Burning the tips with a weed torch might also work.” [Yes! Chemical free vinegar and clove oil! By the way, clove oil has NO demonstrated efficacy for this application. And I’m sorry, but “burning the tips” of barberry is just going to stimulate lots of new growth below the damage. Just out of curiosity, how many people have problems with barberry in their lawn?]

I think you’d notice this in your lawn…

“Crabgrass – what is it? An annual weed with a spreading growth habit. It’s common in the Northeast, in lawns with poor soil conditions. Telltale signs. Lots of bald spots, especially after the first freeze, when crabgrass dies off. How to treat. Have your soil tested. Lime or sulfur may be needed to adjust the pH. Aeration is also recommended. Corn-gluten meal, applied in early spring, can be an effective natural pre-emergent herbicide. [Corn gluten meal, applied in early spring in climates where it rains, is an effective fertilizer for crab grass.]

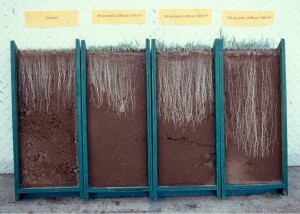

Crabgrass with increasing levels of corn gluten meal.

Courtesy of Tom Cook, Oregon State University.

“Kudzu – what is it? An aggressive climbing vine that’s common in parts of the Southeast and the Midwest. Telltale signs. The thick vine forms a canopy over trees and shrubs, killing them by blocking out sunlight. How to treat. Pull out the vine and, if possible, its taproot. Be sure to bag and destroy the plant or its vines will regerminate. If the root is too thick, paint the stump with horticultural vinegar or clove oil repeatedly, or burn it with a weed torch.” [Ditto the comments for barberry.]

Have fun painting stumps. (Wikimedia)

“Canadian Thistle – what is it? An aggressive creeping perennial weed that’s found throughout the U.S. Telltale signs. Look for outbreaks in vegetable gardens, particularly those with peas and beans. [I have no idea where this little nugget of nonsense came from. It’s a weed! It will grow ANYWHERE! It doesn’t need peas and beans!] How to treat. Repeated hand weeding and tilling of the soil will weaken its extensive root system. [Because tilling the soil is such a great way of suppressing weed seed germination. And it’s really good for your lawn, too.] Planting competitive crops, such as alfalfa and forage grasses, will keep it from returning.” [Yes, do replace your lawn with alfalfa and forage grasses.]

Your new, improved lawn (Wikimedia)

“Fig Buttercup – what is it? A perennial weed with yellow flowers and shiny, dark green leaves. It’s common in many parts of the East, Midwest, and Pacific Northwest. Telltale signs. The weed will start to crowd out other spring-flowering plants. It can also spread rapidly over a lawn, forming a solid blanket in place of your turfgrass. How to treat. Remove small infestations by hand, taking up the entire plant and tubers. For larger outbreaks, apply lemongrass oil or horticultural vinegar once per week when the weeds first emerge. It might take up to six weeks to eradicate.” [Now in addition to pouring vinegar on your lawn, we’ll try lemongrass oil instead of clove oil. Another unsubstantiated application – maybe lemongrass because buttercups are yellow? Makes about as much sense as anything else. It smells nice though.]

Color coordinated weed control

“Phragmites – what is it? An invasive grass species found nationwide, especially in coastal wetlands [where so many of us have lawns]. Telltale signs. Dense weeds can crowd out other plant species without providing value to wildlife. How to treat. Cut back the stalks and cover the area with clear plastic tarps, a process known as solarizing. Then replant the area with native grasses.” [Solarizing pretty much nukes everything that’s covered – not just the weeds. In fact, the rhizomes of this weed are so pernicious I’m not sure that solarization would work. Am still waiting for CR to test their hypothesis in an objective and scientific manner.]

Phragmites rhizome (Wikimedia)

So, Consumer Reports, I’d love to come back to you. But until you start applying your own standard of objective rigor to everything you cover, I’ll have to pass.