“Can I use manure to fertilize my garden?” That’s a common question we get in Extension and on the Garden Professors page. The answer is absolutely, but there’s a “but” that should follow that answer that not everyone shares. And that is…but for fruits and vegetable gardens the manure you apply could be a potential source of human pathogens that could make you or your family sick. There are procedures and waiting periods you should follow to reduce the potential risk to human health from pathogens in manure and other animal products.”

Why manure?

First, application of manures to garden and farm production spaces is a good use of nutrients and provides a way to manage those nutrients to the benefit of growers and the environment. Using the concentrated nutrients in the manures to grow crops reduces what washed downstream in the form of pollution. In addition to adding nutrients to the soil, application of manure and other animal byproducts (bone meal and blood meal, for example) add organic matter to the soil, which improves soil texture, nutrient retention and release, and supports beneficial microorganisms.

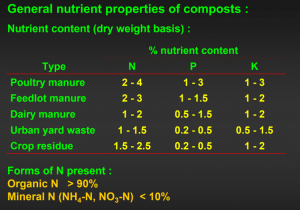

For organic production, both in home gardens and on farms (certified organic or not), manure and animal products are an important input for fertility. For the most part, manures offer a more concentrated (higher percentage) of nutrients by weight than composts composed only of plant residues, so less is usually needed (by weight) than plant composts to apply the same amount of nutrients.

While the nutrient levels of manures and composts can be highly variable, there are some general ranges that you can use to plan your application based on the needs you find in your soil test. (And you should be doing a soil test, rather than just applying manure or compost willy-nilly. Just because the nutrient concentrations are lower than a bag of 10-10-10, you can still over-apply nutrients with composts and manures).

So what are the hazards?

As you’ve probably realized from bathroom signs and handwashing campaigns, fecal material can carry a number of different human pathogens such as E. coli and Salmonella. The major risk around application of manures to edible crops is the possible cross-contamination of the crop with those pathogens. The number one hazard leading to foodborne illness from fresh produce is the application of organic fertilizers – mainly manure, but also those other byproducts like blood meal and bone meal. Add in the fact that the consumption of raw fruits and vegetables has increased over the last decade or more, and you’ll soon understand why Farmers who grow edible crops must follow certain guidelines outlined in the Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA, which you’ll hear pronounced to as fizz-mah) to reduce the potential risk that these pathogens pose to people who eat the crops. Right now, only farms with a large volume of sales are required to follow the guidelines, but smaller producers are encouraged to follow them as best practice to reduce risk and liability. And while there isn’t a requirement for home gardeners to follow the guidelines, it is a good idea to understand the risks and incorporate the guidelines as best practice. It is especially a good idea if the produce is being eaten by individuals who are at higher risk of foodborne illness – young children, the elderly, or those who are immunocomprimised.

The recommendations are also suggested when there’s contamination from unexpected or unknown sources like when vegetable gardens are flooded (click here for a recent article I wrote to distribute after the flooding in Nebraska and other midwestern states).

Recommendations to reduce risk

As previously stated, while these recommendations have been developed for produce farmers, research showing the potential hazards of applying manures means that it is a good idea for home gardeners to understand and reduce risks from their own home gardens.

The set of guidelines outlined by FSMA cover what are called Biological Soil Amendments of Animal Origin (BSAAO – since we government types love our acronyms). Here’s the “official definitions” used in the rules for produce farming:

A Biological Soil Amendment is “any soil amendment containing biological materials such as stabilized compost, manure, non-fecal animal byproducts, peat moss, pre-consumer vegetative waste, sewage sludge biosolids, table waste, agricultural tea, or yard trimmings, alone or in combination”.

A Biological Soil Amendment of Animal Origin is “untreated: cattle manure; poultry litter; swine slurry; or horse manure.”

For BSAAO (we’ll call it raw manure), manure should only be applied to the soil and care should be taken not to get it on the plants. There’s also a waiting period between applying the manure and when you should harvest the crop. The length of the waiting period depends on whether the edible part of the crop comes in direct contact with the soil. Right now the USDA is still researching the appropriate waiting period between application and harvest, so the general recommendation until then is to follow the standards laid out in the National Organic Program (NOP) standards. Research shows that while pathogens may break down when exposed to the elements like sun and rain, they can persist for a long time especially in the soil.

For now, here are the recommendations:

For crops that contact the soil, like leafy greens (ex: lettuce, spinach, squash, cucumbers, strawberries) the suggested minimum waiting period between manure application and harvest is 120 days.

For crops that do not contact the soil (ex: staked tomatoes, eggplant, corn) the suggested minimum waiting period between manure application and harvest is 90 days.

For farmers following FSMA, the waiting periods could change when the final rule is released – some early thoughts are that it could increase to 9 – 12 months if the research shows a longer period is needed.

What about composted manure? Is it safe? The guidelines indicate that there isn’t a waiting period between application of manure that has been “processed to completion to adequately reduce microorganisms of public health significance.” But what does that mean? The guidelines lay out that for open pile or windrow composting the compost must be maintained between 131°F and 170°F for a minimum of 15 days, must be turned at least 5 times in that period, must be cured for a minimum of 45 days, and must be kept in a location where it can’t be contaminated with pathogens again (animal droppings, etc). Farmers have the added step of monitoring and thoroughly documenting all of the steps and temperatures. Now we know that that’s a bit of overkill for home gardeners, but suffice it to say that the cow manure that’s been piled up to age for a few years that you got from the farm down the road doesn’t meet that standard.

“Aged” manure ≠ “processed to completion to adequately reduce microorganisms of public health significance.” So unless you know for sure that you’ve reached and sustained the appropriate temperatures in your compost, you should assume that it would be considered a BSAAO subject to the 90/120 waiting period. Bagged manure you buy at the garden center is likely to be composted “to completion” or may even have other steps to reduce pathogens like pasteurization. Sometimes the label will indicate what steps have been taken to reduce pathogens, or even state that it has been tested for pathogens.

The recommendations also specifically mention compost teas and leachates (a topic we handle with much frequency and derision here at the GPs, since there’s not much science to back up their use and I mention here with much trepidation). For the sake of food safety, any tea or leachate should only be applied to the soil, not the plant. And for home compost that doesn’t even contain animal manure the 90/120 day waiting period should still be observed in most cases since some of what goes into home compost is post-consumer. Since we put pieces of produce in there that we’ve bitten from or chewed on (post-consumer), plus some animal origin items (eggshells) there’s the potential that we could contaminate the compost with our own pathogens – and the environment is perfect for them to multiply.

The Bottom Line

While these guidelines and rules for farmers may just be best practice recommendations that we can pass on to home gardeners, common sense tells us that taking precautions when applying potential pathogens to our edible gardens. An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure, especially when were talking about poop.

Sources/Resources:

- Produce Safety Alliance producer training materials

- National Good Agricultural Practices Program: Soil Amendments (Cornell)

- Biological Soil Amendments of Animal Origin (FDA Fact Sheet)

- FSMA Final Rule on Produce Safety (FDA)

- Manure in Organic Production Systems (ATTRA)