I’m just starting to think about getting my containers planted for the summer and happened to get an email on the topic from a blog reader. John was frustrated with a local columnist’s advice on using gravel in the bottom of the containers for drainage. When challenged, the columnist refuted John’s accurate comments with “logical thinking.” (You can find the posting and comments here.)

Here’s part of the post: “I like to cover the hole with a layer of gravel to improve drainage. Plants need to have their roots exposed to air in the soil to survive and thrive. If the container has no holes for drainage, it will fill with water and drown the plants very quickly. It is better to keep your plants on the drier side than to keep them constantly moist or wet. The big danger in using pots is drowning plants.” Later, he goes on to explain “The potting soil plugs up the drain hole and the water is trapped behind the plug. The layer of gravel creates an area for the water to drain through to escape. The creation of drainage commonly involves a layer of gravel.” This reasoning is part of what he calls “Logical thinking 101.”

As my husband pointed out, this isn’t logical thinking: it’s intuitive. It’s what we think is going to happen in the absence of any evidence. And in this case, it’s wildly inaccurate.

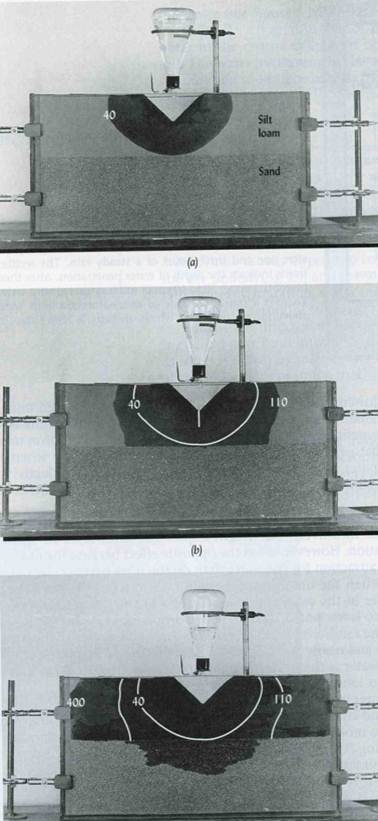

Jeff and I have both discussed the phenomenon of perched water tables in containers as well as the landscape in previous posts and on our Facebook page. The fact is, when water moving through a soil reaches a horizontal or vertical interface between different soil types, it stops moving. Here’s a photo from a very old research paper on the topic:

A layer of silt loam sits above a layer of sand, and water from an Erlenmeyer flask drips in. Intuition says that when the water reaches the sand, it will move more quickly through the sand because the pore spaces are larger than those in the silt loam. But intuition is wrong, as this series of photographs clearly demonstrate. Water is finally forced into the sand layer by gravitational pressure, after, of course, saturating the silt loam.

Intuition has its uses (I am quite proud of my own intuitive powers), but it doesn’t trump reality.

**This is an older post, so I’ve added this link to a peer-reviewed publication on the topic by Dr. Jim Downer and myself.**