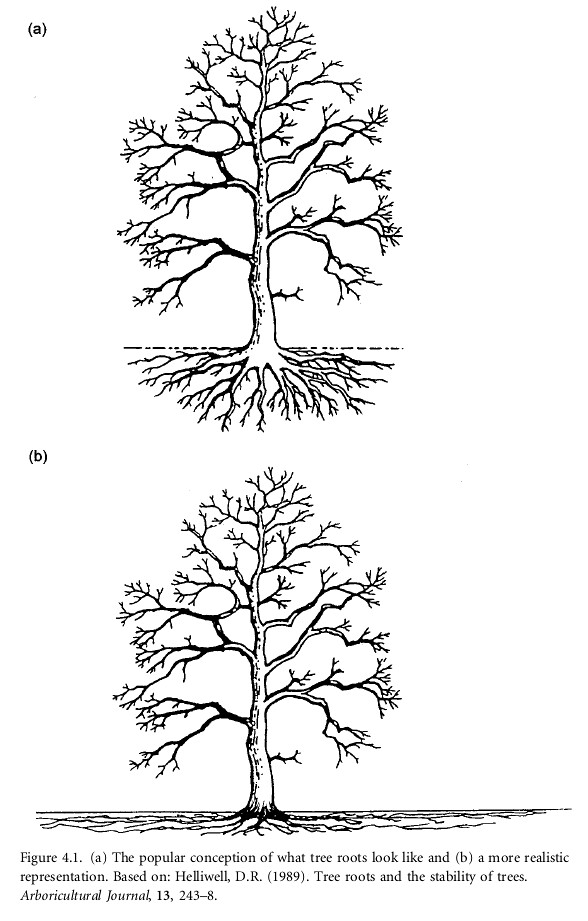

Most of us have witnessed dicot seed germination at some point in our lives – watching the coytledons transform from seed halves to green, photosynthetic structures, while the radicle developed into the seedling root system. This seedling root – or taproot – is important to seedling survival as it buries itself in the soil to provide structural support and to give rise to fine roots for water and nutrient absorption. But that’s where much of our visual experience ends – because we don’t see what’s happening underground. Without additional visual information we imagine the taproot to continue growing deep into the soil. And while this perception is borne out when we pull up carrots, dandelions, and other plants without woody root systems, the fact is that woody plants do not have persistent taproots – they are strictly juvenile structures. Understanding the reality of woody root systems is critical in learning how to protect and encourage their growth and establishment.

Trees, shrubs, and other woody perennials all have juvenile taproots just like their herbaceous counterparts. But these long-lived plants develop different morphologies over time, which are primarily determined by their soil environment. Water, nutrients, and oxygen are all requirements for sustained root growth. Gardeners always remember the first two of these needs, but often forget the third. And it’s oxygen availability that often has the biggest effect on how deeply root systems can grow.

Whole-plant physiologists have known for a long time that “roots grow where they can” (Plant Physiology, Salisbury and Ross, 1992). But this knowledge has become less shared over time, as whole-plant physiologists at universities have been largely replaced by those who focus on cellular, molecular, and genetic influences (and can bring in large grants to support their institution). Sadly, many of these researchers seem to have little understanding about how whole plants function. Simply looking at the current standard plant physiology textbook (Plant Physiology and Development, Taiz et al., 2014) reveals as much. (To be fair, there is now a stripped-down version of this text called Fundamentals of Plant Physiology, [Taiz et al., 2018] but even this text has little to do with whole plants in their natural environment.) If academics don’t understand how plants function in their environment, their students won’t learn either.

Well. Time to move on from my soapbox moment on the state of higher education.

Let’s look at what happens with a young tree as it develops. The taproot grows as deeply as it can, but eventually runs out of oxygen so vertical growth stops. At the same time, lateral root growth increases, because the levels of oxygen closer to the soil surface are higher. These lateral roots, and their associated fine roots, develop into the adult root system, continuing to grow outwards like spokes on a wheel. When pockets of oxygen are found, roots dive down to exploit resources. These are called sinker roots and they can help stabilize trees as well as contribute to water and nutrient uptake.

Gardeners and others who work with trees and other woody species would do well to remember that woody root systems, by and large, resemble pancakes rather than carrots. These pancakes can extend far beyond the diameter of the crown – so this means protecting the soils outside as well as inside the dripline.

Thank you for this very useful post. I’ve learned a lot from your writings as well as from your amazing Great Courses lectures. I’m a small person who relies on hired help to plant trees. I’m happy to say that based on your advice I made sure the burlap around the roots of 4 new trees in my yard were removed before planting last week. Unfortunately, this was not done for another 14 arborvitae that were planted with burlap 3-4 years ago. I’m pretty convinced that the burlap is stunting the growth of these poor trees. Do you have any advice? Should I just stay patient at this point and hope the burlap material rots sooner rather than later? Thank you!

If your trees are not thriving it would be worth getting some help in lifting them out and root washing and replanting. If they are planted densely I’d also increase the distance between them and move the extras elsewhere. Or you can cross your fingers but I’ve seen way too many dead arborvitae hedges to have much faith that they will recover.

Too true! Dead arborvitae all around my neighborhood. Very sad. I’ll have to ask some friends to roll up their sleeves for me. Thank you!

Lack of sufficient water is also leading to the demise of ‘cedar’ hedges where I live on Vancouver Island.

Actually, it’s all due to lack of sufficient water. The question is whether that lack is from (1) lack of summer irrigation, (2) overplanting leading to competition for water or (3) improper planting and root preparation, so roots can’t take up sufficient water.

Because of cold temperatures where I live, I like to start corn on the window sill. Corn grows quite a long initial tap root that reaches the bottom of the seedling starter tray within a few days and then starts to circle. I was wondering whether this will affect growth and yield later on, even if pulled apart. Am I better off using very deep seedling trays that allow for uninhibited initial root growth?

When you transplant just unwind that taproot. It’s flexible.

Roots are so cool!!

I wish I could submit two pictures here, one of a root with signs of double pancaking, first is a sparse ‘pancake’, then 2 feet of more taproot, then next sparse ‘pancake’, and then it looks like more taproot but was broken off.

Then I have another photo of two trees with some roots united into one (harder to see).

Thanks again for yet another informative posting!

Hi Sonia –

What you have is a tree that was planted too deeply – so the lower (original) set of roots suffered from lack of oxygen, and the higher set of roots are adventitious roots. If you go to this post you’ll see what happens to these types of trees over timne.

If you want to become part of the Facebook Garden Professors blog group (https://www.facebook.com/groups/GardenProfessors) you can post your photos there. I’d love to see them.

How do mycorrhizal fungi factor in to the development of tree roots?

I’ve written a peer-reviewed fact sheet on the importance of mycorrhizae for healthy root systems.

This is an excellent overview of the importance of mycorrhizal fungi, especially for those like me who do not have much of a scientific background. Quite a few years ago, I attended a lecture by Dr. Shannon Berch (a research scientist with the BC Ministry of Environment) on MF and have since been trying to understand it better. The focus of her talk was on how MF benefit rhododendrons and she, like you, encouraged people to avoid phosphate fertilizers – including manures.

I’d like to share your peer-reviewed fact sheet with the UBC Forums I participate in but need a shorter URL if that is possible.

Thanks! You are more than welcome to share it with others. You can download (under the “save” button) and send directly to your forum. You can probably also create a shorter link in any message you create by plugging the URL into https://bitly.com/

Thanks so much – I’ll try both.

Our neighbor had a mature paper mulberry in the center front of his house on the roadside. I found the roots of this tree running along the foundations of our house well over 50 feet away from the culprit’s trunk and about 30ft beyond the “drip line”. I wonder whether we should not be advising people to irrigate beyond the drip line.

No, what we need to do is educate people about tree roots. Roots grow where they can find water, oxygen and nutrients. They are not normally going to be a problem to the foundation of a house – otherwise, no houses would have trees anywhere nearby. Reducing water to a growing tree imposes a chronic stress on that tree, which can lead to it failing and/or becoming a hazard to property or people.

Radicle is the correct spelling.

Oops thanks I’ll get that changed. Darned autocorrect.