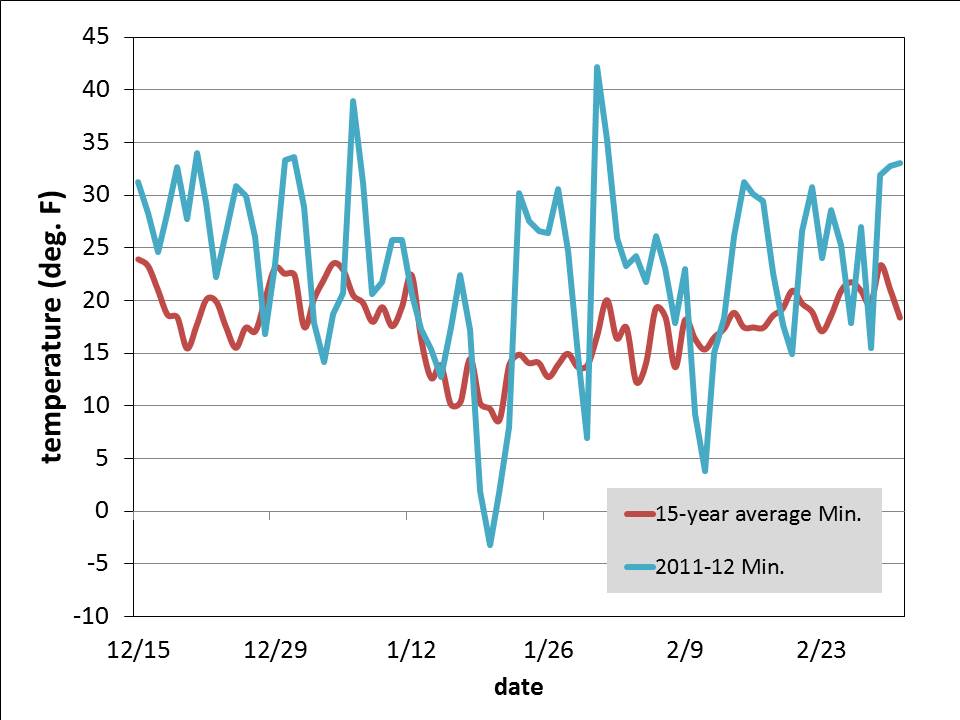

Ok, ‘Hot’ might not be exactly the right word, but winter in the Midwest has certainly been warmer than average this year. I did a little trolling around on Michigan State University’s Automated Weather Network website, which has been logging temperatures and other weather variables around the state for the past 15 years and compared our current winter here in East Lansing to recent years. Since the middle of December our average daily temperatures are 5.2 deg. F above the previous 15-year mean. The departure from the 15-year mean is even greater (+5.6 deg. F) when we look at minimum temperatures.

15-year average Minimum daily temperature and Current-winter daily minimum for East Lansing, MI.

Minimum temperatures are especially important when discussing winter injury to landscape plants since extreme low temps (and the conditions immediately preceding them) are often responsible for many of our winter injury problems. With a generally mild winter and only a few, brief temperature dips below average, one might expect that we will see few winter-related plant problems this spring. However, prolonged exposure to temperatures above average means that plants are beginning to deharden early. We see several signs of this already; such as witch-hazels blooming in protected locations and sap in maple trees running 2-3 weeks ahead of normal http://www.michiganradio.org/post/michigan-maple-syrup-producers-say-season-extra-early-year

February 28, 2012. Witch-hazel in bloom on MSU campus.

While other trees and shrubs may not provide the same outward signs, they are progressively becoming less cold-hardy by the day. Unfortunately, temperatures, like the stock market, rarely move in a straight line. Here in mid-Michigan, temperatures in the single digits are possible throughout the month of March. Given the preceding mild conditions, a sudden, severe cold snap still holds the potential to cause considerable damage to developing buds on trees and shrubs. This type of late from damage may be evidenced by shoot die-back, bud-kill or death of newly-emerging shoots. As always with winter injury, the final result won’t be known until late May or early June.

We had a similar problem on Easter in 2006. The month prior was very warm, even pushing crapemyrtles out much earlier than normal. We woke up to 2.5 inchs of snow, which is no big deal, but that night we hit 21 degrees. It hit crapes, figs, and Jap. maples very hard. IIRC, parts of TN, near McMinnville had temps in the teens that night.

This is precisely why the new cold hardiness zone map is a bunch of hooey! Absolute minimum cold temps are only a (small) part of the story with regard to how well plants perform in a given location, and we’re doing/have done the gardening public a great disservice by focusing so much attention over the past couple of months on the map’s release.

My issue with the maps is the fact that they are changed. If the past 30 years are warmer than your historical average (in KRIC’s case, since the late 1800s), what happens if you enter a period cooler than your historical average? There’s a lot of things, such as PDO and AMO, that affect our long-term climate and what phases those are in match up surprisingly well with historic

620

al averages. These natural cycles coupled with solar weather make a case for a cooler than normal period ahead.

Terry:

Thanks for the comment. To me, the issue with hardiness zones is interpretation (or over-interpretation). If you look at the environmental factors that determine where a plant will or won’t grow, minimum winter temperature is the single biggest limiting factor. Not the only factor, clearly, but if a plant can’t survive the average minimum temperature at a given location, it’s a non-starter. There is nothing you can do, short of growing it indoors that will enable you to grow that plant except as an annual. Think of it another way, if you were going to construct a decision-tree or dichotomous key to determine if a new plant is suitable for your area, what would be your first criteria if it’s not minimum winter temp? Low rainfall? Summer maximum temp? These are limiting but could be overcome with irrigation (assume it’s feasible and you really want that plant). After that, things become site specific; shade, poor drainage, alkaline soils, etc.

What people need to recognize is that hardiness zone is important but it’s just a starting point. If a plant is hardy for your zone it means is that your average minimum winter temperature won’t kill it. Nothing more, nothing less. After that we need to consider all the rest (site factors, pest pressure, design intent) to determine what makes a good selection. Invariably that means

19e0

local knowledge and experience.

CP, it’s very unlikely we’ll enter a “cooler than normal” period any time soon. While natural cycles like the PDO do have a short-term effect, the underlying long term trend is a warming one (meaning the “warm” phase is more significant than the “cool” phase). Besides, the PDO cycle is often irregular and switches states unpredictably.

Bert, can you explain a little how trees become less cold hardy as the weather warms without showing any outward signs? I always thought as long as the buds haven’t opened yet, a tree can still be considered “winterized” for all practical purposes.

Michael:

Good question – and more than I can cover completely in a quick post. The thing to remember is that winter hardiness is not static. Hardiness (the coldest temperature a plant can withstand without damage) changes throughout the winter. Hardiness goes through phases; acclimation, mid-winter (or maximum) hardiness, and de-acclimation. In fact, if you were willing to invest the effort to measure hardiness (I’ll post on how this done next week), you’d find it changes week to week and, to a very small extent, day to day, as environmental conditions fluctuate during the winter. Until we see visible budswell, almost all of these changes are biochemical (inter-conversions of sugars and starches, accumulation or breakdown of organic acids, etc.). In fact, a lot of our typical winter injury to existing trees and shrubs occurs during the de-acclimation phase, rather than in middle of winter during maximum hardiness. This relates to Terry’s comment about the limitation of Hardiness maps. Even though a plant may be able to survive -30 deg. F in Jan., they could still be damaged by -5 deg. in March when they are de-hardening.

There is a good discussion of this on this U. of Minn. website (no, Jeff did not provide a kick-back!) http://www.extension.umn.edu/distribution/horticulture/components/6594-04.html

Bert, thanks for the information. It makes me wonder then if in our high desert climate of Northern Nevada, where we typically get mild winter days well above freezing and hard freeze overnight, if plants ever reach their mid-winter acclimation. So far I’ve had very little dieback, only occasionally at the tips of certain shrubs. But then again, I take great care of my plants, including using plenty of mulch and not letting the soil dry out in the winter. I’ve heard lots of stories about my fellow Nevadans losing their trees to the environment which is easy to do if you don’t spend much time maintaining them.

thanks for the information. I was happy in one aspect of the mild winter in Wisconsin to avoid rabbit damage. On the other hand it was odd seeing a farmer spread manure on a snowless field in February. But a question I thought winter injury could be caused not only buy low temperatures but by wind or a windchill temperature that drops to lower than the hardiness zone of a plant?

Gail, I don’t think trees are affected by wind chill since they have no internal body heat. Wind chill only affects how quickly something cools down. It can’t cool down below the actual outside temperature.

Actually, wind chill can cause a great deal of damage. Cold damage is actually due to dehydration rather than freezing, and wind chill can exacerbate water loss.

I didn’t know that. Thanks for pointing that out, Linda. Still, wind chill is merely how cold it feels to humans and I’m not sure how it would translate to plant hardiness.

Michael, I gave an incomplete (ok, sloppy) answer. The dehydration is caused by ice formation in the nonliving spaces in between the cells. Ice is tolerated here, but causes water to be drawn out of the cell. When enough water is lost, the cells die. The temperatures at which this happens vary among species and is directly responsible for whatever cold hardiness they might possess.

Yes, I remember reading something like that elsewhere. But that sounds more temperature related than wind or humidity related, in which case the wind chill would play a minor role. Or is it that the wind chill exacerbates the situation by freezing the soil deeper (which is usually warmer than air in winter), and thus making it harder for a tree to re-hydrate itself?

Wind strips away moisture from the leaves, which is where the damage will be. Woody tissue and mulched and/or deeper roots aren’t affected much.

What I was thinking about is I have for instance, a tree that is marginally hardy in my zone (despite the new cold hardiness zones). In this case I am not worried about the root hardiness but that the buds would not survive a low temperature combined with high winds producing a windchill 10-20 degrees colder than the hardiness zone for the plant. Or I suppose I could ask if there is a difference between bud or root hardiness?

Gail, roots are the least hardy part of the plant. Since they’re buried in the soil, which is insulated, this makes sense. Dormant buds and woody tissues are the most cold hardy. Newly expanding tissues (leaves, flowers, etc.) have virtually no cold hardiness.

Generally, the cold hardiness that you’ll see on nursery tags is the cold hardiness of the woody part of the plant. But even then, many times this is just an estimate, based on research on related species.