“Put rocks in the bottom of pots for drainage” is one of the most pervasive gardening myths, because it makes intuitive sense (as discussed in this earlier post). Understanding the science behind capillary barriers (what gardeners call perched water tables) is not only more mentally satisfying than the faulty belief but it can help you avoid other gardening practices and products that inhibit water movement within the soil (see earlier posts here, here, here, and here).

Science is not static however, and new research can change our understanding of soil-water relations. A new article was recently published in PLOS One that contradicts the well-established science about layered soils and other media impeding drainage. It’s important to give these contradictory viewpoints careful scrutiny before any deciding whether they represent a true paradigm shift or if they are fundamentally flawed. This article falls into the second category, primarily due to flawed experimental design.

The methods sections of scientific articles are, unfortunately, the least exciting. My approach to reading scientific articles is to read the abstract first and then the conclusion. (Kind of like having dessert before the salad course.) Then I read the introduction and discussion and finally the methods and results. Getting the big picture first prepares me for the nitty gritty details of how the work was done.

Red flags appeared as I read the introductory section: the author compared research on textural barriers between different soil types with their research, which was organic potting media overlaying drainage material. Differences in adjacent soil textures cause perched water tables, or as soil engineers like to call them, capillary barriers. Their presence is a well-established fact. But even given the faulty comparison there is substantial research showing that organic matter can also create capillary breaks with the underlying soil. This means there is a very large body of literature that supports the presence of capillary barriers between soils of different textures and between soils and other materials.

Eventually I got into the methods section. While reading about how to dissect methodology is not the most exciting thing in the world, learning how to do it is exciting – you never know what you will find. Ideally, methodological errors are found during peer review but sadly peer-review is not always of the highest quality. In any case, a careful reading of the methods section of this article generates more questions than it answers.

Without going into excruciating detail about experimental design (there are textbooks written on this), it’s important to understand what you will find in a rigorously designed experiment. There will be an underlying hypothesis (or research question) to explore, a well-designed experimental methodology with sufficient replicates and controls, and appropriate and objective statistical analyses. Paramount to all of this is that variability must be controlled, which means all replicates must be treated identically except for the variables being studied (in this case different drainage materials and their overlying potting media).

Below are many of the problems I identified, along with a brief explanation of why.

- “For trials with sand, a piece of fibreglass mesh (16 x 18 mesh count, approximately 1 mm spacing) was placed over the drainage hole to prevent the sand escaping.” Mesh should have been placed in ALL treatments, regardless if they were needed or not. The presence or absence of mesh has now become an uncontrolled variable (an unforced error to use sports terminology).

- “For each potting medium, trials were conducted with a layer of each drainage substrate to depths of 30 mm and 60 mm…” Weights of the materials (drainage as well as media) should have been made for each treatment replicate so that there are no differences in material weights among the replicates for each treatment. Each drainage substrate should then be shaken to eliminate any large gaps before adding the media on top. Differences in weights of the drainage material is another uncontrolled variable.

- “For each of the three potting media, a baseline moisture level was defined according to the mass of a fixed volume of medium.” These baseline moisture levels need to be reported in the methods. Furthermore, it would have been better to use fully hydrated media, as the wetting time for the different media were likely different.

- “Each filled container was irrigated from above using a watering can with a rose until the water level reached the top of the pot.” There should have been a fixed volume of water added to each container. Differences in how much water was added is another uncontrolled variable.

- “The containers were monitored until water was no longer visibly draining, which took between one minute and three hours.” The differences in time is another uncontrolled variable, as they do not appear to have been used in any of the data analysis. Among the questions one could ask is if there were differences in drainage times within the same treatment?

- “The saturating and draining process caused all the potting media to compact.” Given that the media compacted to different levels, this introduces another uncontrolled variable. A fully hydrated media could have been compacted uniformly. Furthermore, adding water to a dry medium results in an unknown amount of water running down the inside of the plastic containers (which do not bind water), which is a loss unrelated to the experimental goal. Media hydration time varies among media. Unintended water loss is another uncontrolled variable.

- “The compacted depth was measured from one representative sample for each medium with each depth of drainage substrate…” This is a fatal methodological flaw. The depth should have been measured for each container and the average should have been calculated statistically. Furthermore, how was the “representative sample” chosen?

I did read the supplemental files (linked at the end of the article) which I hoped would contain much of the missing information I noted above. They did not – and again I had more questions arise than were answered.

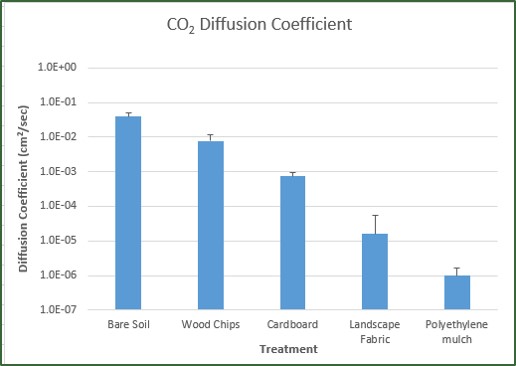

The article was supposedly about drainage – and I expected there to be data generated that looked at drainage times and water loss. If a fixed volume of water was added to each container of fully hydrated substrate, it would have been easy to measure water loss over time. (You can do this at home using university extension information, such as this website from Iowa State University). Instead, the article focuses on water holding capacity -which really doesn’t look at whether or not a perched water table exists -and on developing models.

If you’ve made it this far through my post, congratulations! Here are the takeaways:

- There were numerous design flaws and methodological errors, which introduced uncontrolled variables and created high levels of uncertainty. The data cannot be analyzed statistically and any discussion of the results is pointless.

- This is a good example of insufficient peer review. Had this been submitted to discipline-specific journal (like a journal in the soil or compost sciences), many of the problems I found would have been flagged. But the journal is a general interest journal, meaning that peer reviewers may have had little to no expertise with the science.

The cautionary tale here is don’t be a victim of SSS – single study syndrome. One contradictory article does not dismiss decades of peer-reviewed research and publications unless it meets a very high bar, which this one does not.