As gardeners, we often assign human characteristics to our plants as a way of feeling more connected to them. We talk about their preferences and dislikes for certain environmental conditions and even for each other. The idea that plants have feelings has caused many to believe that plants are sentient and capable of making deliberate choices. (We’ve discussed plant sentience in previous posts that you can see here, here, here, and here.)

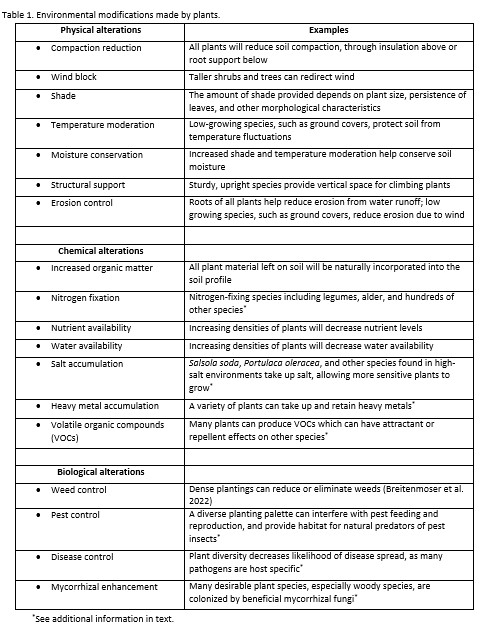

I could spend my time debunking all the books, websites, and social media accounts that promote the pseudoscientific side of companion planting. But this popularized version is a horticultural zombie: it never dies. Instead, I’d rather discuss the ways that plants can change their environment physically, chemically, and biologically – which can influence the survival of other plants. The table below summarizes these methods.

I encourage you to download and read my recently published Extension manual – it’s free and peer-reviewed. In addition to providing solid scientific advice, it will help you understand why the classic example of companion planting – The Three Sisters – may be of historic and cultural interest but is unlikely to benefit plant productivity or soil quality.

Below are some evidence-based companion planting strategies for your gardens and landscapes. More are also available in the Extension manual linked above.

- Perennial companion plants will take a year or two to establish. Annual companion plants should be used if immediate benefits are desired.

- If you are growing perennial crops, avoid using annual companion plants that require yearly soil disruption. Crop growth and yield can be negatively affected.

- Use living mulches on pathways, between rows in vegetable gardens and orchards, and other locations that are not densely planted to reduce competition. Living mulches play a crucial role in protecting soil from erosion as well as biological and chemical degradation, and this improvement may outweigh any drawbacks from competition.

- To reduce competition among desirable plants, choose species whose roots are less likely to interfere with one another. Intersperse large taproot vegetables like carrots and radishes with those whose root systems are shallow and widespread, like corn, onions, and lettuces.

- Avoid invasive species and aggressive native plants. They will be overly competitive for resources like sunlight, resulting in reduced growth and vigor of other species.

- A well-chosen organic mulch will improve plant growth and productivity. A woody organic mulch, such as arborist wood chips, will enhance mycorrhizal populations, improve overall soil health, and control weeds. Arborist wood chip mulches also house predatory spiders and insects, such as ground beetles.

- In vegetable gardens, try to intercrop different species so that individuals of the same species are as far apart as possible from each other. This will reduce the ability of pest insects to infest an entire crop.