Throughout the garden season, extension professionals all across the country get to play detective when trying to diagnose plant diseases and recommend specific controls or preventative measures. We often have to put on our Sherlock Holmes-esque thinking caps and our standard issue detective’s magnifying glass (or microscope) to diagnose plant maladies.

Having a basic understanding of diseases, how they function, and what they look like is key. Gardeners who bring samples or pictures into our office often get exasperated when we play twenty questions trying to figure out if it is a fungus, bacteria, or virus (or something else) causing the issue. Knowing about placement, environment, planting, etc. can all be keys in discovering what might be causing the issue. Sometimes we can’t identify an exact disease at a glance and have to send things to the diagnostic lab on campus, but by looking at signs and symptoms and identifying factors about the plant we can often figure out the type of pathogen causing the issue, or whether it might be environmental, abiotic, or insect related.

What leads to plant diseases?

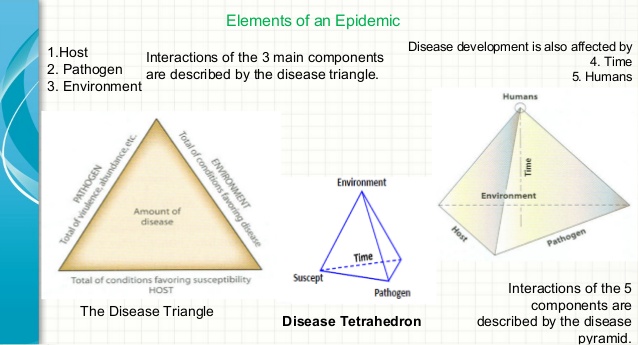

Of course, the thing that causes the disease is a pathogen or a causal agent such as a fungus, bacteria, or virus (or a few other odds and ends like phytoplasmas). But there are other factors at play to get a disease infection started and sustained. You need all of the factors in place for infection. This is often represented as a triangle, where a causal agent (pathogen) must be present with the right environmental conditions and a host plant that can actually be infected by the pathogen. I’ve also seen a plant disease “pyramid” where time is added as another factor (as in, the correct conditions must be present at the same time and for a long enough period for infection to start). And still yet in researching this article I found the PLANT DISEASE TETRAHEDRON, which adds human activity as another factor. What’s next, the plant disease fractal?

But I digress. When a sample comes in to our office, we play twenty questions with the gardener asking about these different factors. Like is it irrigated (many diseases need water to be spread or to develop), does it get shade or full sun, have you seen any insect activity, when do you usually work in the garden, etc. These questions can help us identify parts of the disease triangle/pyramid/tetrahedron that could inform the diagnosis.

Keeping these factors in mind can also help gardeners reduce the likelihood of disease through IPM. For example, viruses require a vector – usually an insect, animal, or human to spread the disease. Many viruses are spread through leafhoppers, bacterial wilt in cucurbits is spread through cucumber beetles, and mosaic viruses like tobacco mosaic virus has many vectors including humans and garden tools (which is why many green industry businesses have strict sanitation rules, including rules for tobacco users and hand sanitation). Knowing that fungi and bacteria can be airborne with spores or splashed by “wind splashed rain” or irrigation water can lead to improved practices like mulching, pruning for good air flow, and plant spacing.

How can you tell which diseases are which?

Let’s face it, many plant diseases look very similar. There are usually what we call spots and rots that can be very similar. But there are some identifying characteristics that help us at least determine what type of pathogen or causal agent is causing the issue.

The first thing to keep in mind is that plant diseases have both signs and symptoms. Signs are the presence of the actual disease causing organism, visible to the eye. Fungal diseases often have mycelia, or fungal threads, and reproductive structures like pycnidia present. You may also see the causal agent itself, such as leaf rust or powdery mildew. Bacteria will often have exudates that ooze out of plant parts, water soaked lesions, and bacteria that stream out of cut stems parts. You can actually diagnose some bacterial infections by suspending a cut stem in water and watching bacteria stream/ooze out of the cut. Viruses are not visible to the human eye, therefore do not have signs.

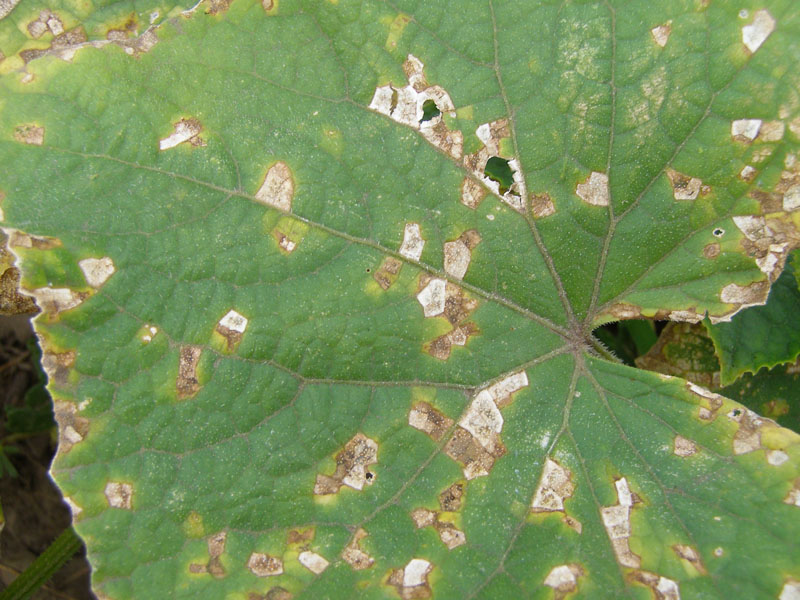

Symptoms, on the other hand, are the effects of the pathogen on the plant. Common symptoms of fungal infections are leaf spots, spots or rots of fruits, chlorosis, and damping off in new seedlings. Bacterial symptoms include leaf spots (often with a yellow halo around them), crown gall, stem/trunk cankers, wilting, shepherd’s crook (like fire blight), and fruit rots. And since bacteria usually depend on streaming through liquids, they often leave definitive patterns for leaf spots that align with vein structures. For example, leaf spots will often be angular because they are “trapped” in between veins on the leaf. The most common symptom of viruses is a mosaic pattern on leaves and fruit, but also crinkling and yellowing of leaves, necrosis, and stunting.

Special mention- phytoplasma: Phytoplasmas are single-celled organisms that aren’t really bacteria, but are descended from them. They don’t have cell walls and are transmitted to plants through an insect vector like leaf hoppers. The most common type of phytoplasma diseases is called yellows (aster yellows, ash yellows, etc.) because plants often turn yellow. The symptoms are often interesting. Witches brooming, which is irregular growth that makes branches look like brooms is common. Aster yellows is a common disease affecting many plants in the aster family. Most commonly, flowers of these plants look distorted and may grow leafy structures instead of flower structures.

To wrap it up

It can be difficult to figure out what diseases are affecting plants, if it is a disease at all. Getting help in determining what disease might be affecting plants can help you treat or prevent the problem in the future. In my next installment of this series, I’ll talk about common diseases, their signs and symptoms, and treatments and preventative measures.

Sources:

https://www.canr.msu.edu/news/signs_and_symptoms_of_plant_disease_is_it_fungal_viral_or_bacterial

https://lms.su.edu.pk/lesson/1660/elements-of-an-epidemic

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/58423213/Screen_Shot_2017_12_14_at_4.58.18_PM.0.png)