Last month I discussed the forecast for the Atlantic tropical season and pointed out that it is likely to be an active one. As I write this, there has already been one named storm (Alberto, which went into Mexico but dropped a lot of rain in southern Texas) and two more areas of potential development are moving their way through the Atlantic (note TS Beryl formed on Friday, June 28 at 11 pm after this was written). Hurricane season has begun! This month I will discuss what a tropical storm is and how they form into hurricanes. I will end by discussing how tropical storms and hurricanes impact gardens and what you can do to prepare for them.

Where do tropical storms and hurricanes form?

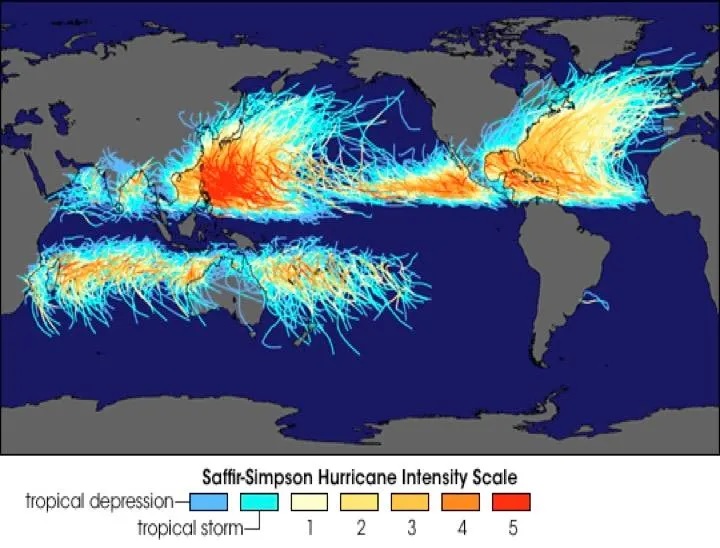

While we think of hurricanes as hitting the southeastern part of the United States, they are actually much more widespread than that. The map below shows that tropical storms can form in both hemispheres and affect every continent except for Antarctica. Here in the United States we see them most often over the Atlantic Ocean but can experience storms on the west coast from time to time as well. The storms are not always called hurricanes, they can be called typhoons in the Western Pacific and cyclones in the Indian Ocean and Australia. To be considered a hurricane or one of these other storms they have to record a sustained wind speed of 74 mph or higher. Storms in the United States that are stronger than that are classified by the Saffir-Simpson scale into categories 1 through 5 depending on how strong the winds are. And of course the wind gusts in the storms can be quite a bit higher than the sustained winds, they are just more localized and last for only short periods.

What ingredients are needed for a tropical storm or hurricane to form?

The prerequisite conditions for hurricanes are: warm, deep ocean waters (greater than 80°F / 27°C), an atmosphere cooling rapidly with altitude, moist middle layers of the atmosphere, low wind shear, and a pre-existing near surface region of low pressure in the surface environment. But you might have noticed from the map that even if these conditions are in place a tropical cyclone is not likely to form if it is not at least 300 or so miles from the equator. This is because of the Coriolis force which acts on moving air on a rotating planet to push air to the right of the original direction of movement in the Northern Hemisphere and to the left in the Southern Hemisphere. Low pressure draws air into the circulation, but the Coriolis force helps it to spin up into a storm with a defined circulation.

The seeds of low pressure where storms form can come from atmospheric waves moving east to west off of Africa, sometimes from stalled fronts over the Gulf of Mexico or along the East Coast of the United States. These usually provide the initial trigger of storm development. But not all waves or fronts can develop into cyclones if the other conditions are not right. The location of typical development depends on the time of year, with early and late storms developing closer to the United States and most storms in the peak period from mid-August to mid-October forming from waves coming off the west coast of Africa.

You might wonder why there are almost no tropical storms in the southeastern Pacific or in the southern Atlantic Ocean. That is because the water is normally too cold to sustain storm development. Since ocean temperatures are warming over time we could see more storms there in the future, especially in the South Atlantic where temperatures are already warmer than the SE Pacific. The tropical season could also become longer as the ocean warms up to 80 F earlier in the year in the future.

Tropical storms and hurricanes move under the influence of winds midway up in the atmosphere which push along the core of the storm as it is growing or weakening. The stronger the core of the storm, the closer the link between the large-scale atmospheric pattern and the storm movement. In the map above you can see that most storms move in a curving pattern that begins in the east near the equator and moves west over time before recurving to the northeast in a clockwise manner. This pattern is caused by subtropical high pressure, called the “Bermuda High”, over the Atlantic but by other names in other parts of the world. The path of each storm is unique due to the weather pattern present at the time of the storm, and sometimes they can take some crazy paths if the weather pattern is unusual.

How do tropical storms become hurricanes?

Usually, a wave of low pressure over the ocean pulls in air towards the center to reduce the pressure gradient. As the air moves in, the Coriolis force causes it to start spinning. In the Northern Hemisphere this spin is counterclockwise. The air above the surface circulation starts to flow out of the storm and drops the pressure at the surface causing the storm to intensify as air rises near the center of the storm. This continues as long as there is a source of energy (warm water) below it and there is no jet stream high up in the atmosphere to disrupt the development of the circulation. When the sustained wind speed reaches 74 mph its designation is changed from Tropical Storm to Hurricane and it stays that way until the wind speed drops as the storm weakens over land or colder water.

What impacts do tropical cyclones have on gardens and what can you do to prepare?

Tropical systems have a variety of impacts depending on where they are and how strong they are. Thoughtful gardeners will consider all the risks that severe weather can have on their gardens and get ready long before the storms hit. The strong and gusty winds are the most apparent impact; they can cause damage to trees, buildings, and plants and can cause significant damage to gardens. It’s a good idea to walk through your property periodically to look for dead or diseased limbs that could become airborne missiles in strong winds (whether or not they are from a hurricane). Decorative items and furniture left outside can damage tree trunks as well as houses and gardens when they become wind-borne. So if a storm is imminent, scout your property to remove anything that could be potentially hazardous.

Another important impact is flooding rain. The amount of rain that falls from a hurricane depends in part on how fast it is moving, since a slow-moving storm can drop more rain on a particular spot than one that is moving through quickly. The storm does not have to be strong to produce a lot of rain either—some of the weaker storms have been great rain-makers. And it does not even need to be an organized storm. Wet tropical systems that are not fully organized into storms have the potential to produce flooding rain, as we saw in southern Florida just a couple of weeks ago with over 20 inches of rain in some locations. The remains of hurricanes can also cause floods far inland, especially if there are mountains to help the air rise. Hurricane Agnes in 1972 had damage from the Caribbean all the way to Canada because of the torrential rains that fell along the Appalachian Mountains as it moved north. Gardeners who live in areas where flooding is likely should plan ahead to divert rain into rain gardens away from their planting beds to reduce erosion and keep soil from becoming saturated.

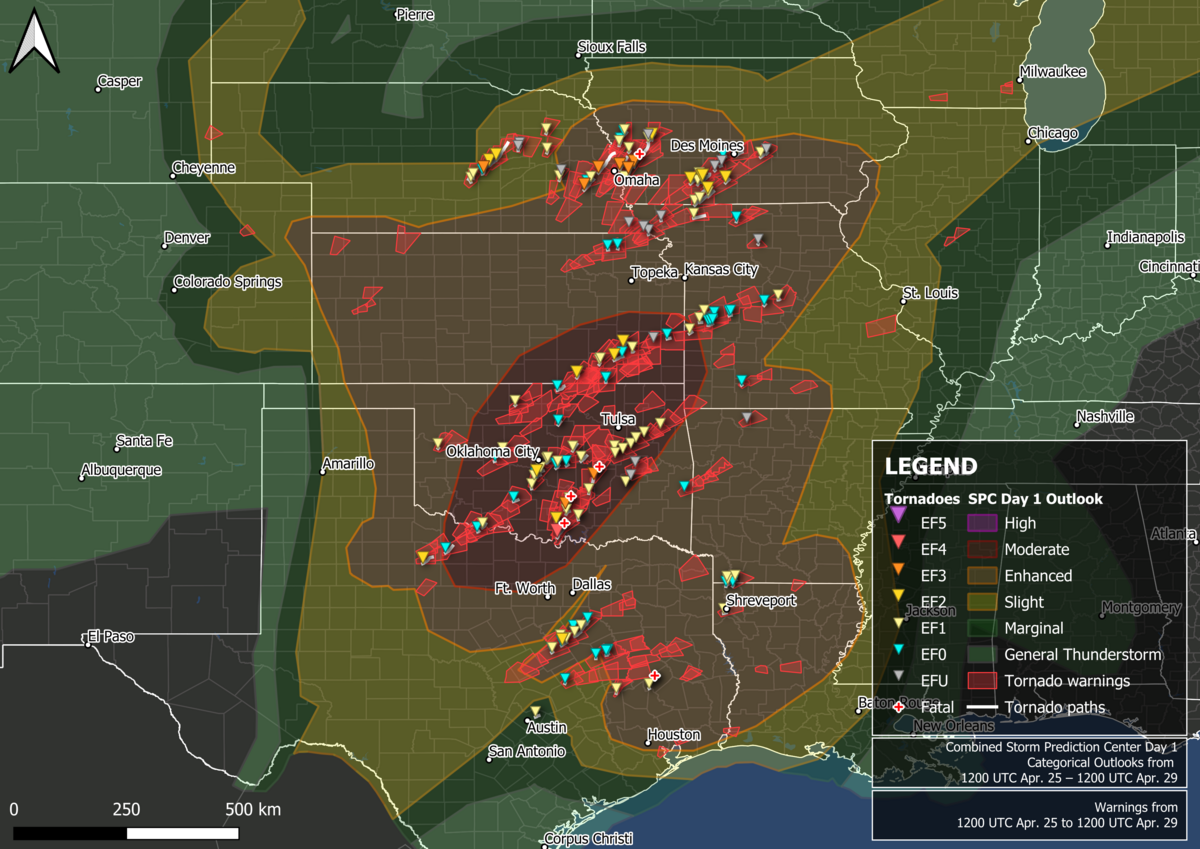

Hurricanes can also cause other impacts too, especially if you are near the coast. Storm surge can drive sea levels up to 25 feet above mean sea level as the water builds a dome under the area of lowest pressure that moves along with the storm until it makes landfall. If you are in a coastal area, you need to consider what the elevations of your land and house are so you know how much the water might rise in a strong storm. Another impact is the strong storms that can occur in the spiral bands outside the main circulation. These storms can hold weak tornadoes as well as heavy rain and gusty winds. In Hurricane Ivan in 2004, we had a tornado in Athens GA at the same time that the main storm was making landfall along the coast several hundred miles away.

As gardeners, it is important to keep in mind that tropical storms and hurricanes are not all bad. The rain that comes from these storms may include 30-40 percent of the summer rain that is expected to fall in a tropical area, and if few storms come, drought is more likely. But the damage is also like to stress your gardens (not to mention the gardeners!), so learning more about these storms and planning ahead to prepare for the damage they might bring is a good thing for every home owner in an area prone to tropical activity to do now, before the storms come.