If you follow current weather news, you have likely read the astounding story of the recent lake effect snowfall in Buffalo, New York, and other areas downwind of the Great Lakes, where over 6 feet of snow fell in just a day or two in some locations. My mom, who still lives in Grand Rapids, Michigan where I grew up, reported that in her city some areas got up to 30 inches during the same time frame. So this month I want to discuss lake effect snows and how heavy snows can affect your trees and gardens.

What is lake effect snow?

Lake effect snow is snow that is caused or enhanced by differences in the temperature of warm water in the lakes and the cold Arctic air that blows over it. Calling it “lake effect” is a bit of a misnomer, since cold, dry air blowing over a warmer ocean can cause the same effect. In the United States, it most often occurs downwind of the Great Lakes, especially in fall when the lakes are still warm and the air blowing in from the north is much colder and drier than the lake surface. It can even sometimes occur downwind of smaller lakes or reservoirs if the conditions are just right.

As the cold dry air crosses the warm water, copious amounts of water vapor evaporate into the air mass and once that warmer, moister air blows onshore again clouds drop huge amounts of snow in the areas downwind of the lakes. The snow usually falls in heavy bands that drop snow in areas that are highly dependent on the direction of the wind. Often the bands are just a few miles wide but if you drive through one your visibility can drop to near zero in just a short distance. When I lived in Valparaiso, IN, near the south end of Lake Michigan, winds blew straight from the north for much of the month of December 2000 dropping 32.0 inches of snow when Decembers there usually get just a few inches, thanks to the lake effect snow that occurred. (I moved to Georgia the next month, although it was not because of the snow—mostly.) As winter progresses and the lakes get colder with more ice cover, lake effect snow is reduced because of the decrease in available water vapor so fall and early winter are the prime times of year for the heaviest lake effect snow.

In this case, weather forecasters were well aware of the potential for record-breaking snow because of their knowledge of the lake temperatures plus the computer-generated forecasts of wind direction and persistence over time. Winter storm warnings and maps of predicted snowfall were produced well ahead of time. Even so, the amount of snow that was produced from this historic event is still amazing.

Source: Carolyn Thompson / AP Photo

Why did Buffalo experience such extreme snowfall amounts?

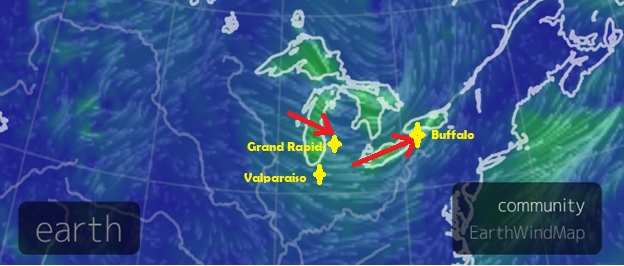

Buffalo is known for its incredible snowfalls due to its position downwind of Lake Erie, a long and shallow lake that is usually warm well into fall. The long distance of the wind blowing over the lake (called the “fetch”) allows the air to pick up tremendous amounts of water that becomes snow as it hits the land NE of the lake; the exact location of heaviest snow depends on the direction of the wind over the lake (see my poorly drawn map annotated on a screen capture of the Earth Nullschool streamline map for the day of the heaviest snowfall below). In this month’s case, the lake had temperatures well above the long-term average, and the wind across the lake was very consistent over a few days, allowing the snow to pile up dramatically. In some locations snow was falling at the rate of several inches an hour and the extended period of snowfall allowed it to build up to over six feet in some locations in just a day or two, while other areas not along the direct path of the wind received much less. The area of heaviest snowfall shifted as the winds changed direction over time.

The result of this weather event was the nearly complete shutdown of Buffalo and other areas affected by the heavy snow. Even a city that experiences as much annual snow as Buffalo does can be stopped in its tracks for a while by the sheer volume of snow that has to be removed. The weight of the snow also caused problems for a number of building roofs and caused some power outages as well. Even the professional football game between the Buffalo Bills and the Detroit Lions had to be moved from Buffalo to Detroit because of the impossibility of clearing out the open-air stadium and the roads around it for fans to get there safely (or at all).

Does climate change affect lake effect snow?

A warming climate does have some impact on the conditions that make lake effect snowfalls most likely. The lakes are generally staying warmer later into the fall, so when cold continental air does develop over Canada and move across the lakes there is more potential for large amounts of water vapor to be evaporated, increasing the chance of heavy snow. It is likely that there may be some reduction in the production of the coldest, driest air in polar regions, but it will still occur often enough for lake effect snow to continue to be a climate factor downwind of the lakes. It is more difficult to say how or if the weather patterns that determine the direction of wind flow will change as the climate gets warmer.

Source: Dan Taylor-Watt, Commons Wikimedia

How does heavy snow affect trees and gardens?

Lake effect snow is often very wet and heavy which makes damage to trees and power lines more likely. An average snowfall may have about one inch of water equivalent in ten inches of snow, but in a lake effect snow it is often more like six inches of snow to one inch of water equivalent which means it is very dense stuff to shovel. Wet snow may weigh up to four times as much as newly fallen regular snow per square foot. No wonder most heart attacks from clearing snow occur when this very wet and heavy snow has fallen.

The weight of this much snow can easily collapse the roofs of buildings. It can also do a lot of damage to tree limbs and shrubs, especially when the wet snow sticks and freezes to either needles or leaves adding to the weight on the limbs. Trees and bush varieties that are brittle or have poor branching structure are especially vulnerable to damage from heavy snow. Snow on the ground can help insulate the plants from very cold weather, but the moisture that is left after the snow melts can cause saturated soils that can negatively impact roots. Salt added to help melt the snow from paved surfaces can also harm plants and the deep snow cover in some lake effect storms can also provide cover for voles and other critters that like to nibble on bark.

For me, lake effect snow in my Michigan winter when I was growing up was the ultimate fluffy Christmas snow, with big fat flakes drifting down like a picture postcard. But when the flakes come down fast and heavy the holiday snow becomes a problem that can affect travelers, home owners, and gardeners too. I hope that as you travel over the holidays this winter, the snow that you see, whether you stay or go, is a delight and not an obstacle to spending time with your friends and family.