I like catchy memes as much as the next person. They’re easily memorized and passed on. But “Save the planet, plant a tree” has always bugged me for two reasons. First, and probably most importantly, this simplistic mantra absolves people of doing MORE to improve our environment. It’s a “one and done” approach: “Hey, I planted a tree today, so I’ve done my part.” That’s hardly a responsible way to live in a world where climate change is a reality, not a theory. Planting trees (and other woody plants) needs to become part of a personal ethic dedicated to improving our shared environment, and that includes reducing our carbon footprint in MANY ways.

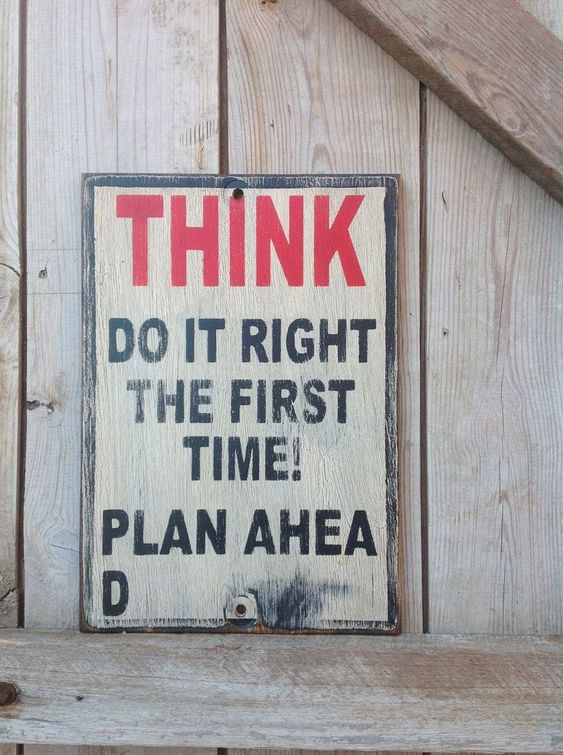

Second, and more germane to this blog, is that most people don’t know how to plant trees (and that includes an awful lot of professionals who should know better). Planting trees properly requires an understanding of woody plant physiology and applied soil sciences. Otherwise, newly planted trees are likely to die due to one or more problems:

- Poor plant species selection

- Mature size too large for site.

- Species not adapted to urbanized conditions. This includes insistence on using native species whether or not they tolerate environmental conditions far different from their natural habitat.

- Poor/improper soil preparation

- Working amendments into the soil before, during, or after planting. Your goal is to keep a texturally uniform soil environment.

- Digging a hole before seeing what the roots look like. It’s like buying a pair of shoes without regard to their size.

- Poor quality roots

- Most roots found in containerized or B&B trees are flawed through poor production practices. If you are using bare root stock, you don’t have to worry about this problem.

- Can’t see the roots? Well, that leads to the next problem.

- Improper root preparation

- No removal of burlap, clay, soilless media, or whatever else will isolate the roots from its future soil environment. Take it all off.

- No correction of root flaws. Woody roots don’t miraculously grow the right direction when they are circling inward. They are woody; it’s like trying to straighten a bentwood chair.

- Improper planting

- Planting at the wrong time of year. It’s best to plant trees in the fall, when mild temperatures and adequate rainfall will support root establishment and not stress the crown.

- Not digging the hole to mirror the root system, especially digging too deep.

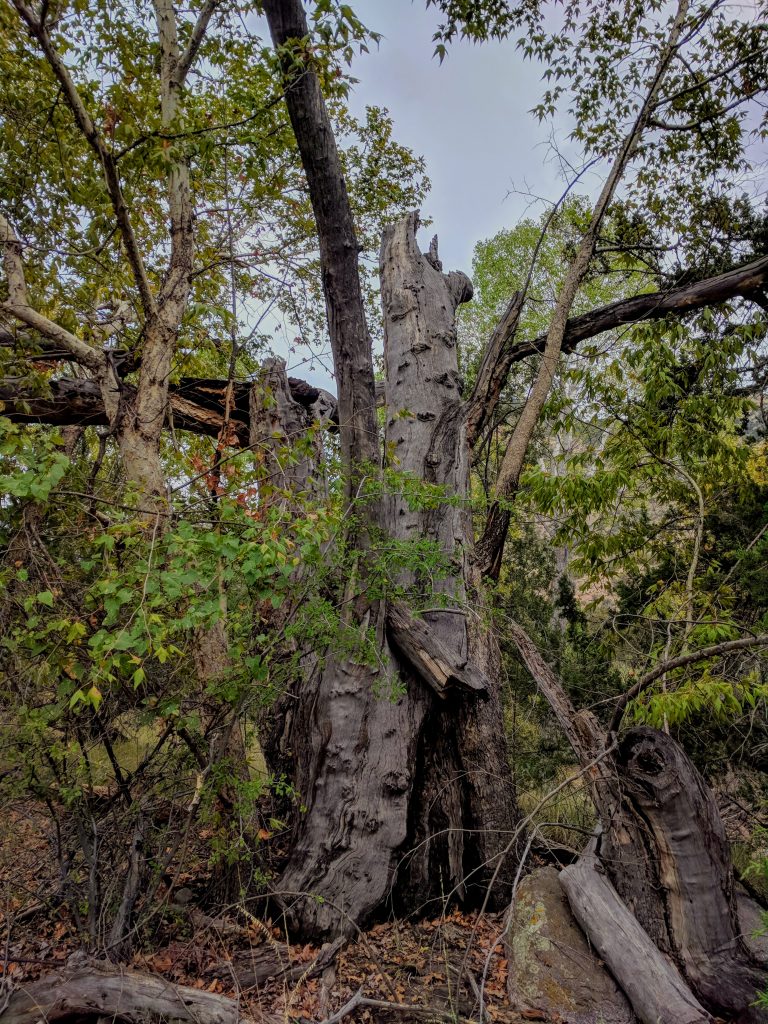

- Failing to place the root crown at grade (which means the top of the root crown should be visible at soil level). Look at forest trees if you are not familiar with what a root crown looks like.

- Stomping or pressing the soil around the roots. That just eliminates the air space in soil pores.

- Adding “stuff” like transplant fertilizers, biostimulants, etc. They are not needed and you risk creating nutrient imbalances when you add “stuff.”

- Poor aftercare and long-term management

- Failing to add arborist wood chips as a mulch on top of the planting area. Regardless of where you live, natural woody material as a mulch is critical for root, soil, and mycorrhizal health.

- Failing to irrigate throughout the establishment period and seasonally as needed. Trees will continue to grow above and below ground, and without a similar increase in irrigation the trees will suffer chronic drought stress during hot and dry summers.

- Adding fertilizers of any sort without a soil test to guide additions. Trees recycle most of their nutrients; don’t add anything unless you have a documented reason for doing so.

That’s a lot to think about when you are planting a tree – but when you understand the science behind WHY these actions should be avoided, then you can devise a better plan for planting. And if it all seems to be too much, I have created a twelve-step planting plan that might be useful. Please feel free to share it widely!