As my colleague Fred Hoffman says, the horticultural silly season is upon us. This week I heard from one of our European readers, questioning the use of cornmeal as a fungicide. He referenced an online article entitled “Cornmeal has powerful fungicidal properties in the garden.” He hadn’t been able to find any reliable information and thought it might make a good topic for our blog. So Johannes, this rant’s for you!

If you’ve followed the link to column in question, you’ll see that the original “research” is attributed to one of Texas A&M’s research stations in Stephenville, TX. But it’s not really research – it’s just an observation on what happens when you don’t plant the same crop two years in a row; in this case, rotating corn and peanuts reduces peanut pathogens. This is hardly news – it’s one of the reasons agricultural scientists recommend crop rotation as part of an IPM program. And have for decades.

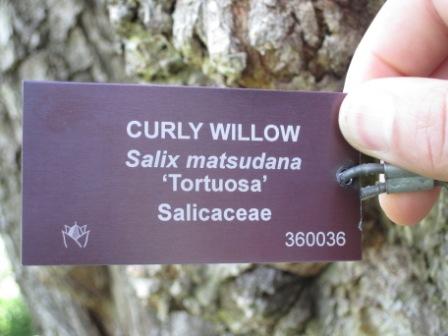

Then we’re referred to “further research” (at an undisclosed location) where cornmeal was shown to contain “beneficial organisms.” Well, no, cornmeal doesn’t contain organisms, beneficial or otherwise. Microbes can grow on cornmeal, and in fact cornmeal agar is commonly used in labs as a growth medium for many species of fungi. And has been for decades.

Nevertheless, we’re informed that a gardening personality has “continued the study and finds cornmeal effective on most everything from turf grass to black spot on roses.” This is directly refuted by Dr. Jerry Parsons, who by happy coincidence is an extension faculty specialist at Texas A&M. His informative (and hilarious) column on brown spots in lawns states “Lately there have been claims made that corn meal and a garlic extract is effective. This is absolutely false! Everyone trying to do the “environmentally friendly-to-a-fault” thing have been wasting their money. They would have been better off making corn bread and using their garlic for cooking purposes!”

Dr. Parsons continues: “Let me explain how these University tests and recommendations have been misrepresented in a desperate attempt to find an organic fungicide. The corn meal was investigated by a Texas A&M pathologist as a way to produce parasitic fungi used to control a fungus which occurs on peanuts.” (This directly relates to my earlier point that cornmeal agar has a long history of use in fungal culture.)

It boils down to this: if you have a healthy soil, it will probably contain diverse populations of beneficial microbes, including those that control pathogenic fungi. You don’t need to add cornmeal – it’s simply an expensive form of organic material. So you can ignore the directions in the article on how to incorporate cornmeal into the soil, or make “cornmeal juice” to spray on “susceptible plants.” Just nurture your soil with (repeat after me) a thick layer of coarse organic mulch.

(As a footnote, let me say how annoying it is when gardening personalities grant themselves advanced degrees or certifications in their titles. C’mon folks – if your information is so great, do you really need to pretend you’re someone else?)

(Another footnote: I discussed this myth more in 2012. Be sure to check this link out too.)

UPDATE: Since this is a myth that refuses to die, I’ve published a peer-reviewed fact sheet on the topic. Feel free to pass on to others.