Some odds and ends today that I either #1 was asked to post or #2 couldn’t resist posting. First for the picture that I was asked to post.

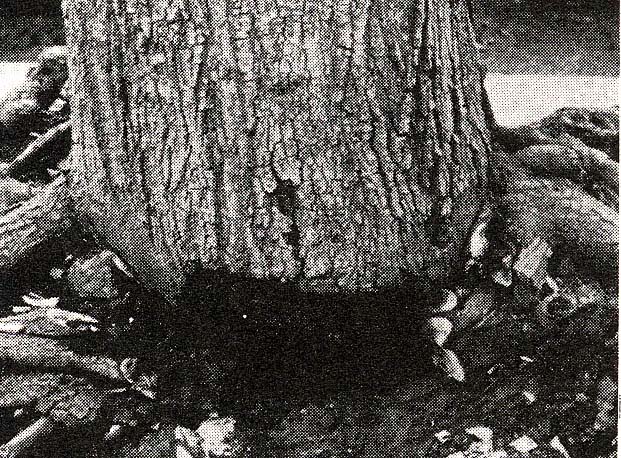

This, as far as we can tell (we being myself, my technician, and our grounds department), is the American elm tree that was being planted in that picture from 1909 which I posted on January 21. Dutch elm disease was devastating here in the mid 1900s as it was everywhere, but this region of the world was lucky and there were a number of escapes — and resistant trees (that’s an ongoing project of mine — working with DED resistant elms — I’ll probably post more about it this spring). Anyway, the tree is a little smaller than I would normally expect for an elm of this age, but the proximity of the road and sidewalk could easily have stunted its growth.

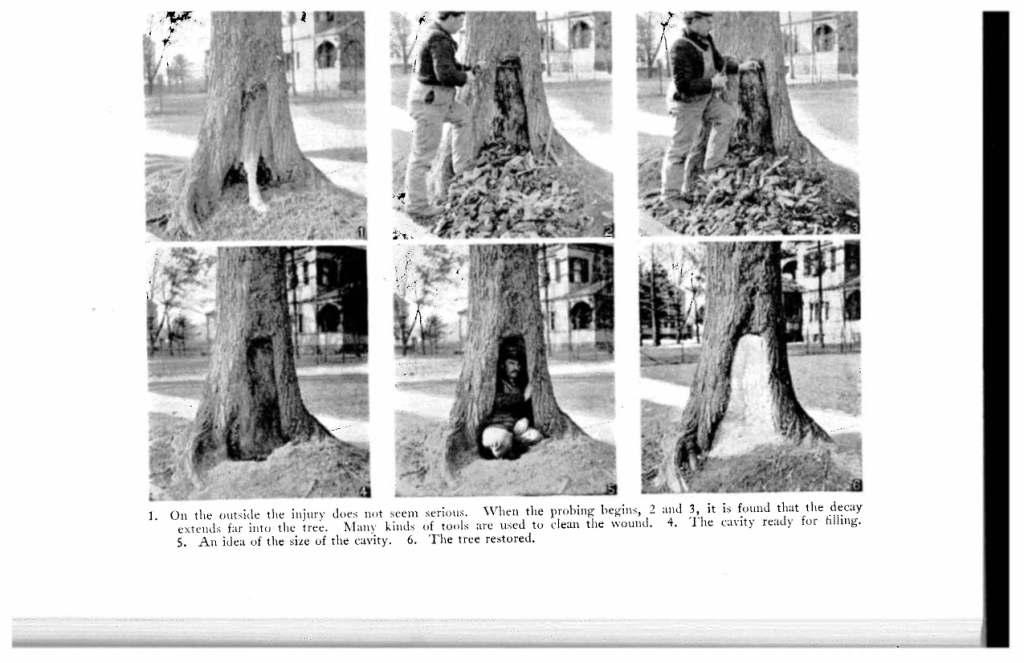

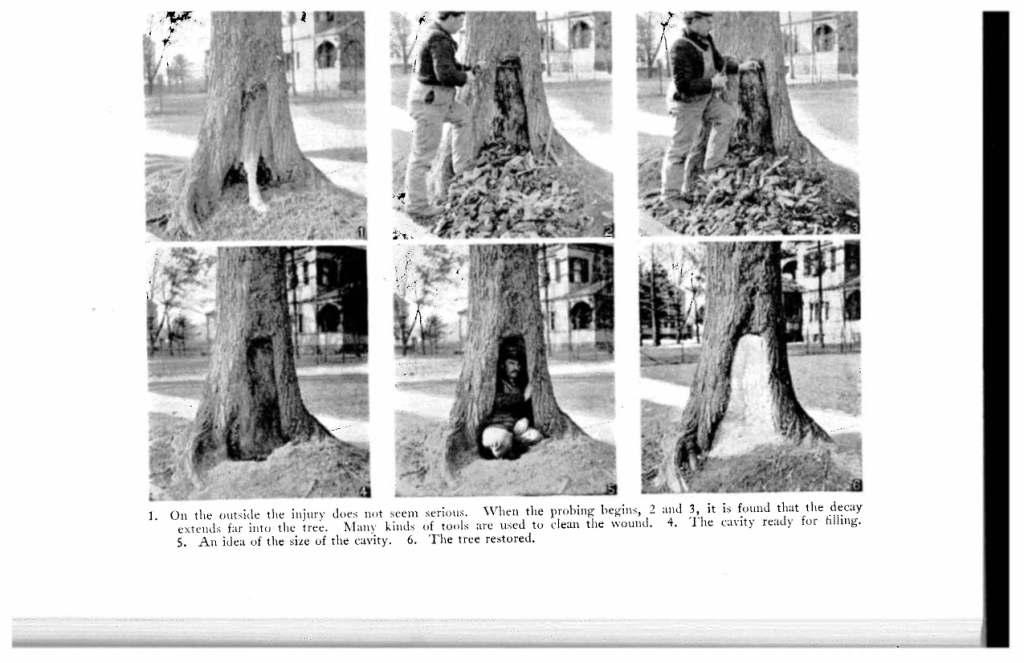

Now for the stuff that I can’t resist posting — mostly having to do with Bert’s post on January 25. Chad (my technician — if you follow the blog you’ll remember him, 6’4″ — etc.) was showing me a book titled Shade-Trees in Towns and Cites by William Solotaroff published in 1911 and it had this great shot of filling a tree cavity. So here it is:

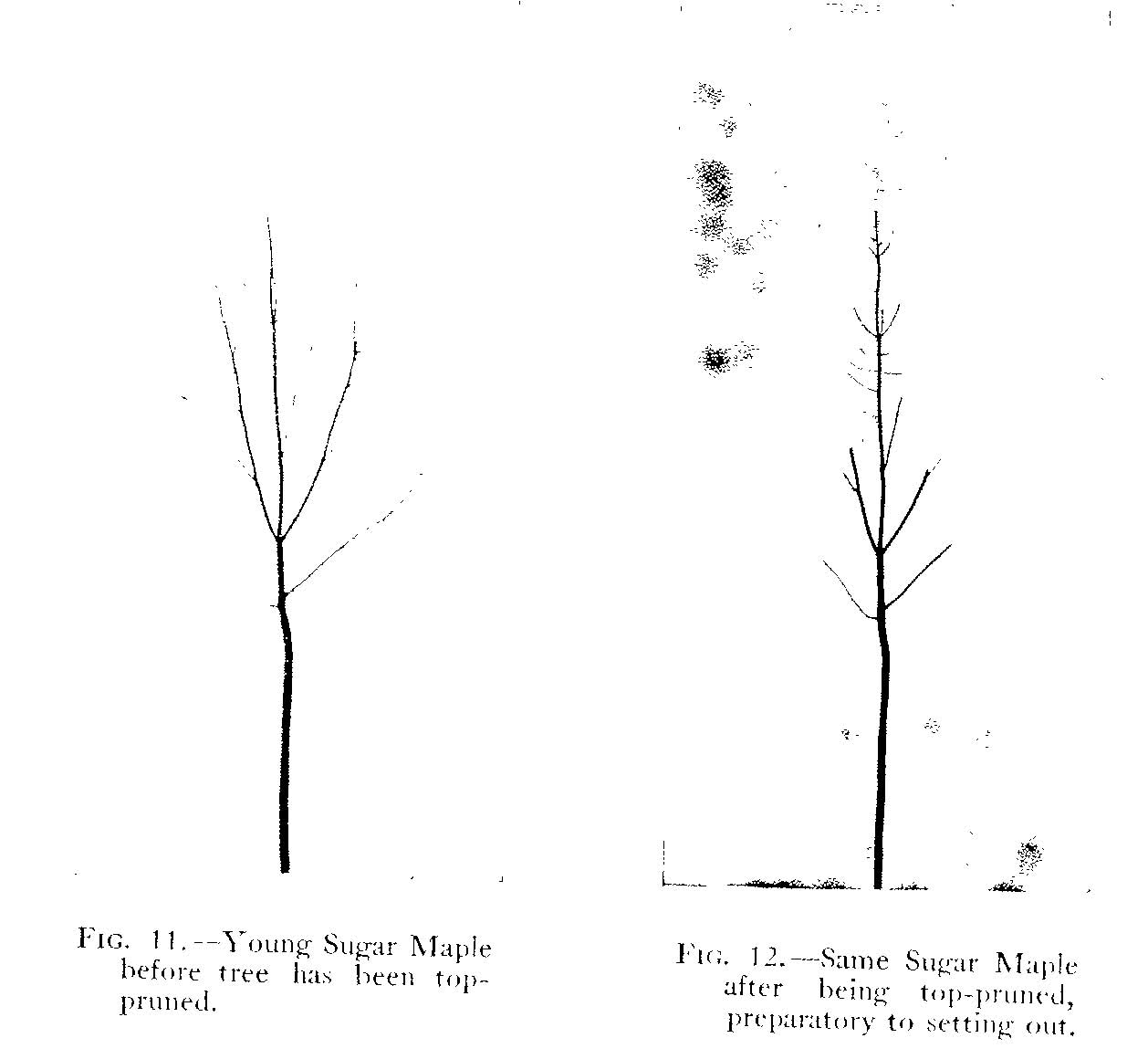

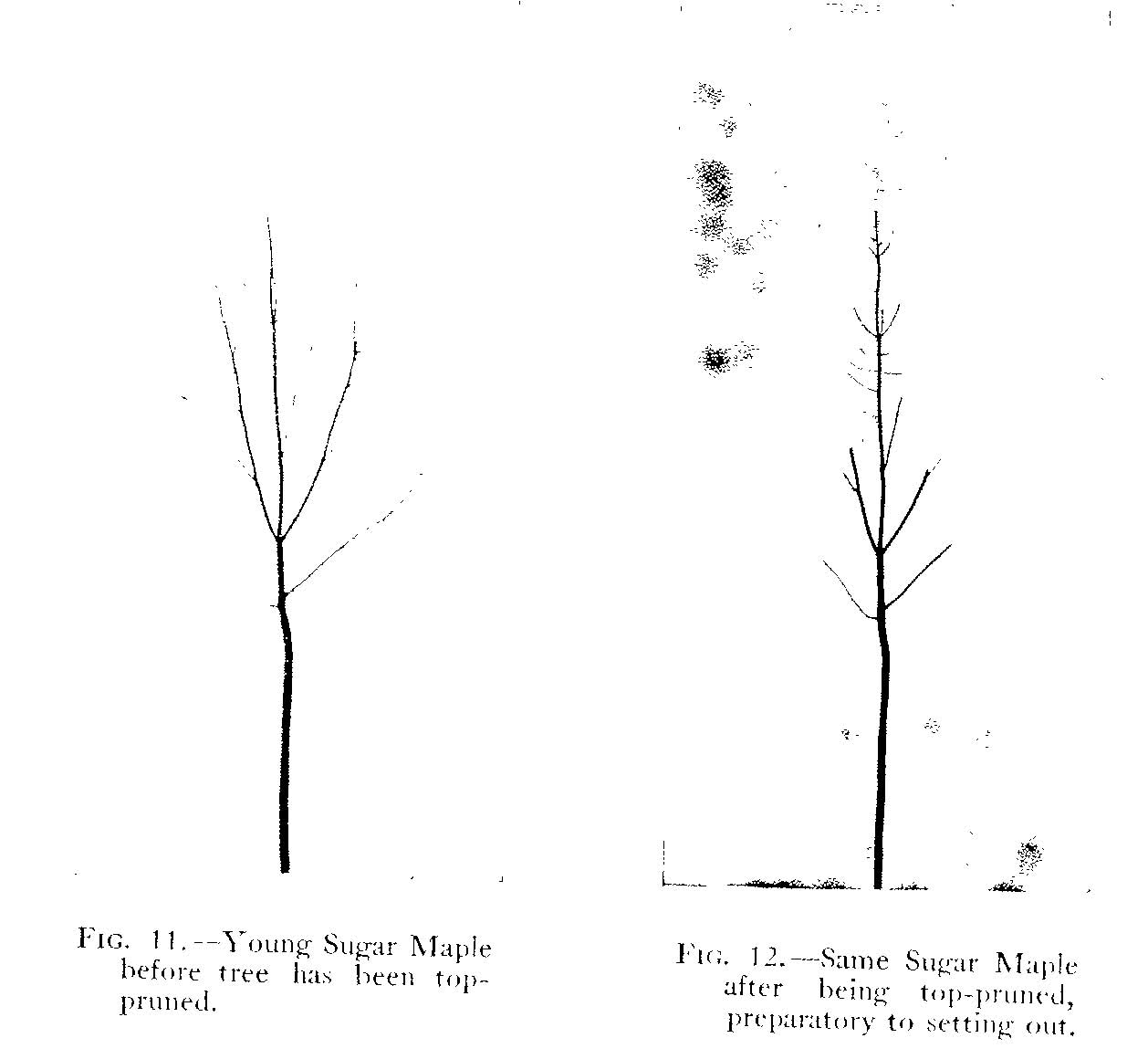

The book also had a great shot of what they did to a trees canopy before they planted:

This type of pruning isn’t necessary at all. When trees are planted they adapt to the amount of roots which they have by producing fewer, or smaller leaves.

Update:

Here is a photo of the leaves of a freeman maple which was severely rootpruned right before planting and, below it, the leaves of a similar maple whose roots were left pretty much intact (both plants were container grown).

As you can see, trees have their own methods of dealing with root loss — no need for us to come in and clip their tops off. Now, two years later, both of these trees (and all of the others in the research plot) look pretty much identical.