Nothing seems to take homeowners more time, or generate more frustration, than maintaining their lawns. In addition to mowing, fertilizing, and applying pesticides for weeds, insects, and diseases, gardeners fret about removing thatch and aerating the soil. Commercial interests have taken note and pedal various “aerifying” products like soap (cunningly described in non-soap terminology), spiked sandals, and thatching rakes. Previous posts (here and here) have addressed ways to decrease fertilizer and pesticide use. This post will look at the science behind aeration of home lawns.

Iron maiden torture devices in sandal form

More lawn torture via thatching rakes

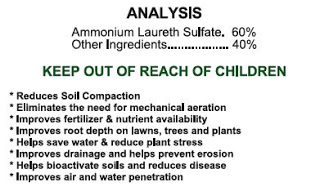

That first ingredient in this aerifying product? It’s soap.

First, let’s acknowledge that most research has focused on maintaining turf on golf courses and playing fields. Neither of these are good models for home lawn management because home lawns have different functions. The turf that one might find on a putting green, for instance, is devoid of most life except for closely mown monocultural (or oligocultural) grasses. The management of these grasses is chemically and physically intensive to preserve a completely unnatural system. Yet these management techniques, including core aeration and vertical mowing (aka verticutting), have seeped into the lucrative home lawn maintenance market, especially to address the dreaded thatch layer common in many home lawns.

What is thatch?

Briefly, thatch is caused by organic material accumulating at the base of grass plants. (It is NOT caused by lawn clippings, which are small and nitrogen rich – they are broken down quickly.) Accumulation of thatch is said to lessen lawn resilience and increase disease, but this appears to be a classic CCC (correlation conflated to causation) error. I’ve seen nothing in the literature to suggest that thatch causes these problems. Instead, I see evidence that thatch is yet one more negative result of poor lawn management. Removing thatch, without addressing the CAUSE of thatch, is an exercise in futility.

Lawn with thatch layer

Natural grassland

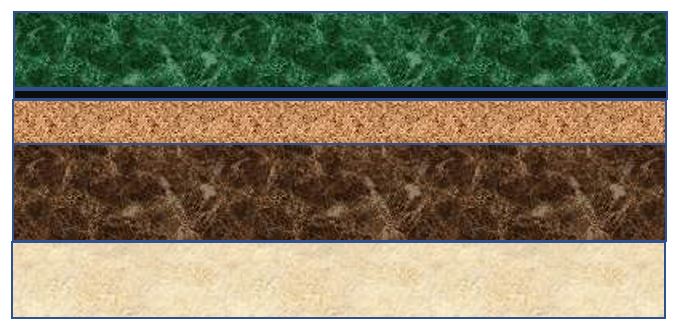

Look at these two images of grass-covered soil: one is a typical lawn, and the other is a natural grassland. There are no roots extending below the “thatch” layer in the lawn, while grassland soils support deep and extensive root systems. The problem with the lawn is that the system is not well aerated, meaning that the grass roots are shallow and contribute to the buildup of thatch. Lack of aeration also inhibits a robust community of microbes, which are necessary to decompose the organic material that makes up thatch.

So, lack of poor oxygen and water movement between the grass layer and the underlying soil creates a dead zone in that soil, with life restricted to those few inches of soil where oxygen and water can penetrate. Thatch accumulates and underlying roots from nearby trees and shrubs are forced upwards into the lawn to obtain water and oxygen. This is where lawn maintenance companies promise to fix the problem through core aeration or verticutting.

It’s not goose poop. It’s core aeration.

Vertical mowers look impressive but do they work?

Does core aeration and verticutting improve home lawns?

While there is scant research on home lawns, the results are fairly uniform: core aeration does not reduce thatch accumulation and does not improve grass coverage. Verticutting can decrease thatch slightly but decreases grass coverage and reduces turf quality. Several quotes from published research stand out:

- “All cultivation practices [which included core aeration and verticutting] resulted in some quality loss at various times during the spring transition period compared to the control.”

- “Thus, under homelawn conditions, core aeration and vertical mowing should only be used if a specific problem exists and not as routine practices to prevent thatch accumulation.”

- “After two years, no treatments consistently reduced thatch accumulation compared to the non-cultivated control.”

There is no published research, anywhere, that supports these techniques in maintaining healthy home lawns. So, it’s time to stop using these heavily promoted products and practices and instead focus on why lawns accumulate thatch in the first place.

It’s all about the oxygen!

There’s no question that lawns can be heavily compacted, but it’s not because grasses can’t tolerate foot traffic. Think about those hundreds of thousands of bison that use to roam the Great Plains grasslands. Even modern cattle ranching, done sustainably, does not damage pastureland by compacting the soil. There’s something else going on in home lawns that creates compacted conditions and the cascade of negative effects that follow; it’s improper soil preparation and management.

When sod is laid for home lawns, several inches of compost are tilled into the soil bed. The tilled soil is then flattened with a roller, and then a layer of sand is applied. Then the sod (which consists of grass and growing media and a mat of some sort) is arranged. And voilà! You have a turfed landscape that more closely resembles a five-layer dessert than a functional grassland. Those layered materials restrict the movement of water and oxygen, and this restricts root growth into the underlying native soil. Not only do these barriers create a shallowly-rooted turf, they compound the problem by stimulating ethylene gas production in grass, further inhibiting root growth. To top it off, the anaerobic conditions in the lower layers restrict microbial decomposition. As decomposition and root growth slow, thatch accumulates. And homeowners despair.

So, thatch serves as a warning sign that soil conditions are poor – and any attempts to permanently remove thatch without addressing poor soil preparation and management are going to fail. Possible corrective actions to improve soil structure and function are beyond the scope of this column; over the years we’ve had blog posts touching on this topic and I encourage readers to explore our blog archives.

Sod layers

Jello layers