Linda got a few comments and questions on her post a couple of weeks ago on fertilization and insect resistance. This is an issue I’ve been peripherally involved with over the years so I wanted to share a few thoughts. First, the relationship between plant nutrition and insect resistance is extremely complex. We often have difficulty predicting how a plant is going to respond to fertilization, let alone predict how an insect is going to respond to how the plant responded. I haven’t kept up but Koricheva (2002) reported over a dozen different theories have been proposed to explain insect response to plant nutrition. One of the factors that makes it difficult to generalize about plant/insect interactions is that various insects feed on different plant parts in different ways; some are leaf feeders, some suck sap, some bore into wood, some feed on seeds or cones. How an insect feeds can affect its response. To stick with an illustration I’m more familiar with, we can look at insect response to plant drought stress. Bark beetles are widely known to key in and attack pines and other conifers under drought stress but pine tip moths prefer succulent buds and new growth and are more likely to attack well watered trees. It’s not unreasonable to think there are similar differences with nutrition.

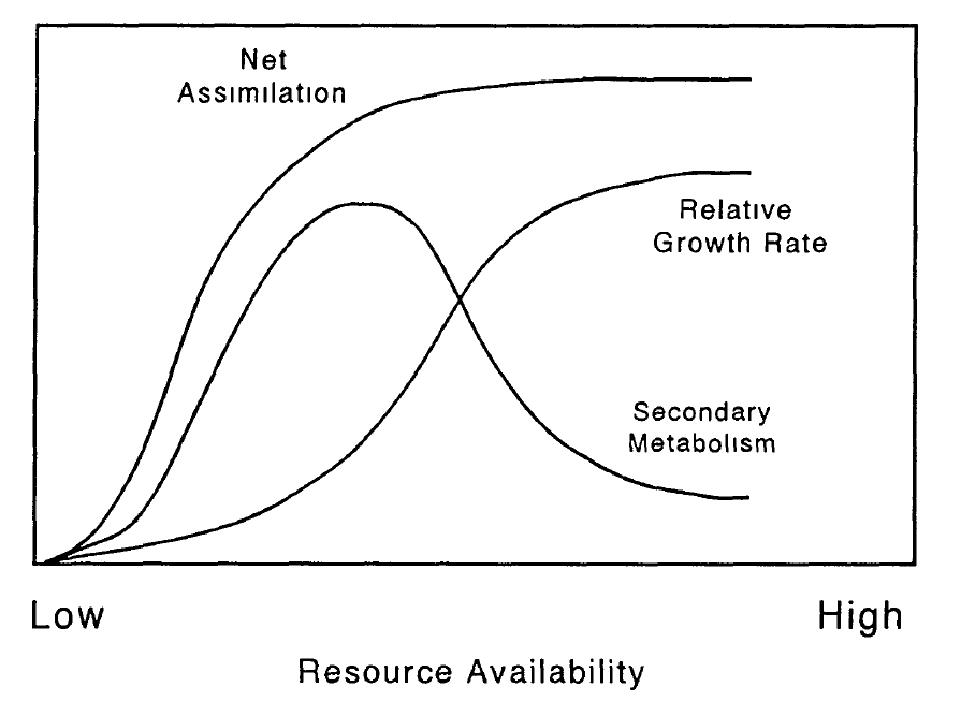

Nevertheless, as noted above, there have been attempts to come up with general theories on the effect of plant nutrition on insect resistance. One of the most widely cited is the Growth-differential balance theory proposed by Dan Herms and Bill Mattson (“The dilemma of plants: to grow or defend.” Q. Rev. Biol. 67: 283-335). A quick check on Google Scholar indicated this paper has been cited by over 1,400 other papers, which is an astounding number and speaks to its influence. The basic premise of the theory, as suggested by the title of the paper, is that plants make a trade-off between allocating carbohydrates for growth or allocating carbohydrates for secondary defense compounds. Dan Herms subsequently applied the theory in synthesizing the literature on woody ornamentals in his 2002 paper, “Effects of Fertilization on Insect Resistance of Woody Ornamental Plants: Reassessing an Entrenched Paradigm.” (Environmental Entomology 31(6):923-933.). I have heard some arborists and others use this paper to argue that we shouldn’t fertilize landscape trees at all. The problem is they oversimplifying the theory – which is understandable, this is pretty heady stuff. They get the ‘trade-off’ idea; if plants grow fast they produce lots of yummy stuff for bugs. But what is often overlooked – even though Herms makes a point to say it – is that when nutrition or other plant resources are low; there is no trade-off.

This figure from Herms and Mattson illustrates the idea. If nutrients are deficient and we fertilize a plant the plant may increase growth and secondary compounds; it’s not always an either/or situation. The bottom-line remains the same; nutrient deficient plants can benefit from fertilization or correcting the factors (e.g., alkaline pH) that made them deficient in the first place.

Koricheva, J. 2002. The Carbon-Nutrient Balance Hypothesis Is Dead; Long Live the Carbon-Nutrient Balance Hypothesis? Oikos 98 (3): 537-539