This article was originally published in my weekly newspaper column in the Charleston Gazette-Mail. Articles are archived at wvgardenguru.com.

A few weeks ago I made my way to South Dakota for the annual meeting of the National Association of County Agricultural Agents (where fellow GP and I made the rounds at the trade show scrutinizing wacky products). It is a fun conference made even more special this year by the fact that WVU President E. Gordon Gee was in attendance as the conference co-keynote speaker and recipient of the Service to American/World Agriculture award. But I digress…..

Two days into the conference something wasn’t quite right. I kept feeling worse and worse, and by Wednesday I was confined to my hotel room (save for a venture out to the conference banquet for dinner). I would not have been functional for the rest of the trip save for the kindness of a co-worker who went through the pharmacy red tape to procure and deliver “the good stuff” to my hotel room.

I thought I had a sinus infection at best (I get them often) and the flu at worst (yes, it was really that bad). But guess what — I’m just really allergic to South Dakota. Two days after my return, I was nearly back to normal (well, my normal, anyway).

Those who know me know that I suffer from the occupational hazard of allergies. Irony dictates that my allergies are only to about two dozen plants and two molds (that occur in mulch/compost). Lucky me!

My best guess is that I had a reaction to the corn pollen of South Dakota. It makes sense — while we do grow some corn here in West Virginia, the Mount Rushmore State boasts an estimated 4.75 million acres of corn. I don’t think I was tested for corn pollen allergies, but since corn is not a major crop here, it may not be part of the common test.

I tell this story not for sympathy (well, OK, maybe a little) but it brings up a good illustration about pollination strategies of plants.

You see, plants like corn rely on chance and wind to spread their genes around. In corn, the pollen drops from the male flowers (the tassel on the top) to the stigma of the female flower (the end of the silk sticking out of the cob). The process relies on lots of pollen being released into the air, since there is a good chance that a lot of it will miss the target. Corn pollen is usually heavy, therefore it doesn’t blow too far from the plant (unless there is lots of wind).

This is why you don’t get a good corn crop if you don’t have a big block of corn in the garden — just one or two rows doesn’t drop enough pollen to pollinate all the flowers. When the silks don’t get pollinated, you’ll end up with incomplete cobs missing kernels. This can also happen if the corn is in bloom during a long period of rain — the rain washes all of the pollen off before pollination can occur.

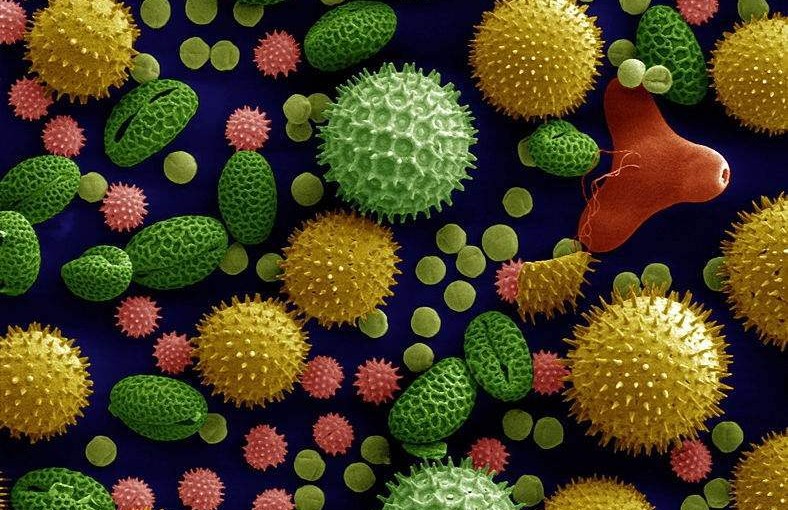

Most of the major allergen-producing plants are wind pollinators — trees, grasses, ragweed. They all release copious amounts of pollen into the air hoping for it to land in the right place.

Since these plants don’t leave the pollination to chance, they generally produce less pollen. Some good examples are fruit trees (apples, peaches, pears), sunflowers, squash, goldenrod and roses. Since they don’t release it into the air, they usually aren’t considered major allergens.

Still yet, some plants want to take no chance with their next generation. Self-pollinating plants don’t rely on pollen being spread to different flowers — they take care of business themselves. These plants are perfectly fine without crossbreeding with other plants.

Sometimes, these plants are so dedicated to self-fertilization that they make it difficult for the pollen to leave the flower. Bean flowers have a lower lip that curves upward to protect the reproductive parts inside. Tomato flowers are nearly completely enclosed. You may see bees going from flower to flower, but their search for food is in vain — they can’t get into the flower. Their buzzing does help dislodge the pollen inside the flower, but they don’t have access to spread it around. Producers that grow tomatoes in greenhouses where there is no wind to knock the pollen loose either buy boxes of bumblebees to release in the greenhouse, or use something like a vibrating toothbrush to help the flowers self-pollinate (no joke).

This is why you can plant two different tomatoes just a few feet apart and not have them crossbreed, but you would have to plant squash up to two miles apart (or protect the flowers) to guarantee that you get the same variety if you plan on saving seeds. This is why the most commonly saved seeds, at least in this area, are tomatoes and beans — they are easy to guarantee that you won’t get something other than what you plant.

So if you learn anything from this article, check out how plants pollinate before you save their seeds, and take plenty of allergy meds with you if you go to South Dakota.