Hybrid, heirloom, organic, non-GMO, natural….there’s lots of labels on those seed packets or plants you pick up at the garden center or from your favorite catalog. Since the seed-starting season is upon us, let’s take a minute to look at some of the information – and mis-information – you might find on those seed packets.

For a brief overview, here’s a short video segment I recently shot for the Backyard Farmer Show, a popular public TV offering for Nebraska Extension:

Hybrid vs. Heirloom vs. Open Pollinated

Just what is a hybrid anyway?

Simply put, a hybrid is a plant (or any living organism, technically) with two different parents. Take for example the Celebrity variety of tomato, which is very popular among home gardeners. In order to get seeds of Celebrity tomatoes, whoever produces the seeds must always cross two specific parent plants to get those specific seeds, called an F1 hybrid.

These parents have been developed through traditional breeding programs (read: the birds and the bees — no genetic engineering here) from many different crosses. Hybridization has occurred naturally ever since there were plants. Man has been directing this process throughout most of his agricultural history to get better crop plants. How else would we have many of the vegetables and fruits that we take for granted today?

Crops like corn have very little resemblance to its wild counterpart, many thanks to selection and even crossing of superior plants by humans over the centuries. University researchers and seed developers use this natural ability of plants to cross to direct the formation of new varieties that improve our ability to produce food.

What is an heirloom?

Perhaps the first question we should ask is, what is an open-pollinated seed? An open-pollinated variety is one whose genetics are stable enough that there is no need for specific parent plants, because the seeds produced from either self-pollination (as in the case of beans and tomatoes) or cross-pollination with the same variety will produce the same variety.

An “heirloom” plant is basically an open-pollinated plant that has a history, either through age (50-plus years) or through heritage (it has a family story).

Take for example the Mortgage Lifter tomato.

It was developed by a gentleman living in West Virginia (my native state -there are two competing stories as to who developed it). For all intents and purposes, the Mortgage Lifter started out as a hybrid, since the gardener in question developed the tomato by crossing many different varieties to find one that he liked. He sold so many of them to his neighbors that he was able to pay off the mortgage…thus its interesting moniker.

It just so happened that the genetics of this tomato were stable enough that its offspring had the same characteristics, so seeds could be saved. Therefore, it was technically an Open-Pollinated variety. Over time, the tomato became considered an heirloom because of both its age and unique story. This story has played out many times, in many gardens and in many research plots at universities.

There are some trying to revive the practice of plant breeding for the home gardener. If you’re interested, check out the book “Plant Breeding for the Home Gardener” by Garden Professor emeritus Joseph Tychonievich. Who knows? Maybe in 50 years we will be celebrating your plant as a distinctive heirloom.

So which is better – Heirlooms or Hybrids?

There are pros and cons to hybrid plants and heirlooms both, so there really isn’t an answer as to which one you should plant. It really boils down to personal choice. Hybrid plants tend to have more resistance to diseases and pests, due to the fact that breeders are actively trying to boost resistance. This means that there will be higher-quality produce fewer inputs. This is why hybrids are popular with farmers — nicer, cleaner-looking fruits with fewer pesticides. Many times hybrids are also on the more productive side, thanks to a phenomenon called hybrid vigor.

Heirlooms, on the other hand, help preserve our genetic diversity and even tell our cultural story. Heirlooms do not require a breeding program, so there is built-in resilience, knowing that we can produce these seeds well into the future with little intervention. But we do have a trade-off with typically less disease-resistance and less consistency on things like yield. Since they are open-pollinated, they are often a good choice for people who enjoy or rely on saving seeds from year to year.

GMO-Free or Non-GMO

As we have pointed out several times before, when it comes to seeds for home gardeners, the label of GMO-Free is largely meaningless and sometimes mis-leading. Whether or not you believe the prevailing science that shows that genetically engineered plants are safe for human consumption, you can rest assured that there are currently no genetically engineered seeds or plants available to home gardeners. Not on the seed rack at the box store nor your local garden center. Not in a catalog or online.

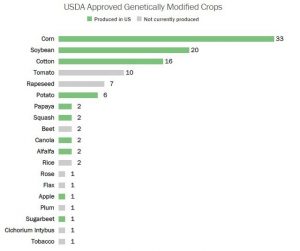

Here are two assurances to that statement: A majority of the things that you grow in the home garden don’t have a genetically engineered counterpart. Only

12 genetically engineered crops have been approved in the US, and only 10 of those are currently produced. Most of these are commodity crops that home gardeners would not even produce, such as cotton, sugar beet, canola, and alfalfa. A few more have counterparts that are grown by home gardeners, but are vastly different from those grown by commodity producers (soybeans vs. edamame soy). And some just aren’t that very widespread (there are some GE sweet corn cultivars and squash cultivars, but they aren’t widespread on the market).

So for the most part, there aren’t any “GMO” counterparts to the crops you’d grow in the home garden. They don’t exist.

The other assurance is that genetically engineered crops are not marketed or sold to home gardeners as a matter of business practice or law. In order to purchase genetically engineered seeds or plants, it is current practice in the United States that you must sign an agreement with the company that holds the patent stating that you will not misuse the crop or propagate it (and before we get into the whole intellectual property argument – plant patents and agreements like this have been around since the early 1900s – it isn’t new). So you know that you aren’t buying genetically engineered seeds since you aren’t being asked to sign an agreement. Plus, these companies make their money by selling large quantities of seeds, they just aren’t interested in selling you a packet of lettuce seeds for $2.

So since there aren’t any GMOs available to home gardeners, why do all these seed companies slap that label on their packets? Marketing, my dear! It started off with just a few companies, mainly using the label to compete in a crowded market. And fear sells. The label has spread to more and more companies as this fear and anti-science based marketing ploy has spread…both by companies who jumped on the fear bandwagon and by those who took so much harassment from the followers of the non-GMO crowd or they lost sales to people sold on the non-GMO label that they finally gave in. Unfortunately for some companies, slapping the non-GMO label on a product seems to give them permission to charge more, even if has no real meaning….so buyer beware.

Treated vs Non-Treated

Seed treatment usually involves the application of one or more pesticide such as a fungicide or insecticide to protect against pathogens or pests, mainly in the early stages of growth. A good example would be if you’ve ever seen corn, pea, or bean seeds at the local feed or farm store that are bright pink or orange in color. These seeds have been treated with a fungicide to offer short-term protection against damping off. Some crops are also treated with systemic insecticides, such as imidacloprid, to protect against insect damage. There’s been a big emergence of organic seed treatments, so treatment doesn’t necessarily mean the crop can’t be labeled organic.

Treated crops are most-commonly found at farm supply stores and aren’t generally marketed directly to home gardeners. You’ll likely not find them at most box stores or garden centers catering exclusively to gardeners. Many packets will specify whether they are non-treated or treated.

Organic and Natural

In seeds, the term Organic largely refers to seeds harvested from plants that were certified organic. Generally speaking, these seeds were produced on plants that received no synthetically produced fertilizers or pesticide sprays. However, it does not mean that the plants were not treated with pesticides. There’s a great misunderstanding about organic production – there are a number of pesticides and even seed treatments approved for use on organic crops. Typically, they are produced from a plant or microorganism extract, naturally occurring mineral, or other organic derivative. So organic does not equal pesticide free (on the seed rack or on the grocery shelf).

There are a few different levels of “organic,” too.

Sometimes small producers use the label in a general sense to mean that they follow organic practices, but aren’t certified. The process for certification is often onerous and costly for small producers, so they often opt to not get it. This is especially true for producers that market exclusively to a local clientele, like at the farmers market, where they can rely on their relationship with customers and reputation to speak for their practices. Some food companies may also use a simple “organic” label – either as a design choice, or because their product wouldn’t qualify for a certification.

“Certified organic” means that the producers practices have been certified to meet the requirements laid down by a certifying agency. A certifying agency could be a non-profit or a state department of agriculture. The requirements and practices vary from entity to entity.

“Certified organic” means that the producers practices have been certified to meet the requirements laid down by a certifying agency. A certifying agency could be a non-profit or a state department of agriculture. The requirements and practices vary from entity to entity.

“USDA Certified Organic” means that the producer has been certified by the USDA as a follower of the guidelines set forth by the National Organic Program (NOP). This is usually seen as the most stringent of the certifications, and is standardized nation-wide.

“USDA Certified Organic” means that the producer has been certified by the USDA as a follower of the guidelines set forth by the National Organic Program (NOP). This is usually seen as the most stringent of the certifications, and is standardized nation-wide.

For certified organic producers, a requirement for production is that all seeds or plant sources are organic. For home gardeners, I often question the need for organic seed, even if organic methods are followed. A quick literature search turned up no evidence that garden seeds contain pesticide residues. There’s been no evidence that plants translocate systemic pesticides to their seeds or fruits(Though it is impossible to prove a negative). Since seeds are located inside some sort of fruit, there would be little chance of residue on the seed from a pesticide application. And even if there was some sort of residue, it would be such a small amount in the seed that it would be so dilute in the mature plant that it would likely be well below any threshold of threat to human or wildlife health…or even measurability.

Personally, I may opt for the organic seed at home if it were the same price of the “conventional” on offer…but that organic label often includes a pretty good price differential. Knowing that there likely isn’t a huge difference in what is in the packages….my penny-pinching self will reach for the conventional, cheaper option.

And what about “natural.” That one’s easy….there is no recognized definition of natural by the USDA or any other body. Companies use that term to mean whatever they want it to mean….meaning that it is relatively meaningless in the grand scheme of things.

Where to find me on the web:

Work Blog: GROBigRed

Good summary, John.

Thanks!

I don’t view comparing cost of organics-to-conventional choice of a specific variety and weight as a simple Apples-to-Apples decision. I buy from a reputable supplier who sources the best quality seed on their wholesale market, and which makes the effort to build long-term relationships with small farmers who specialize in crops and maintain high quality control standards.

10 to 20 cents/pkg difference is not even worth thinking about. Asking the larger question of how my seed supplier enriches its local community’s economy and ecology and the world of horticulture in general is worth my time and resources.

The details about no commercial home garden gmo seeds are a gross simplification. It has been proven by Monsanto (when they sued farmers whose crops Monsanto contaminated) that GMO crops readily pollinate other crops. Many types of corn have been tested for GMO crossing and are proven contaminated.

Thanks for your comment. It is true that cross pollination can occur in garden crops that have a GMO counterpart (corn, soy, and summer squash). However, the agreement that producers sign when buying genetic engineered seeds requires them to plant them at a distance far enough away from non-GE crops to limit cross pollination. It does happen, but is rare and would only have trace amounts of DNA – they wouldn’t be a full genetically engineered plant or necessarily have the engineered traits. Most seed producers in this country take this very seriously, and in areas where seed production is prevalent there are registry maps so that cross-pollination doesn’t occur (not even among non-GE crops).

As for legal issues regarding GE companies suing producers for cross contamination, there’s been quite a bit of myth surrounding what has actually happened. Despite widespread claims of lawsuits from Monsanto and others, many reputable sources affirm that there never were any such lawsuits for farmers being sued if they planted crops that were cross-contaminated with a neighbor’s GE crops. There were cases where farmers were obtaining GE seed without signing the agreement (black market seed or purposefully saving the seed from GE crops) were sued. The most famous case that was featured in many documentaries was that of farmer Percy Schmeiser. His case is the one that many point at to say that Monsanto was suing farmers for accidental cross-pollination. But it was actually found that Mr. Schmeiser purposefully planted his crops near his neighbor’s GE crops, then sprayed glyphosate herbicide (Roundup) to select plants that had specifically developed the “RoundUp Ready” trait, saved those seeds and planted them. It was sort of a scheme to try to get “proof” for media, but it backfired on him – since he had purposefully planted seeds with the trait without signing the agreement and much of his testimony was contrary to what he was saying on the documentaries, the court ruled that he was infringing Monsanto’s patent (though he was not required to pay damages).

Further reading:

https://www.biofortified.org/2015/12/lawsuits-against-farmers/

https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2012/10/18/163034053/top-five-myths-of-genetically-modified-seeds-busted

https://gmoanswers.com/ask/why-does-monsanto-sue-individual-farmers-and-other-ag-biotech-companies-dont-if-they-do-it

Hi John,

I’m hoping you can answer this question. Several websites claim that by buying seeds or seedlings of Seminis-developed varieties like Early Girl and Lemon Boy you are indirectly supporting Monsanto/Seminis. Is this true? Does every nursery and every seed shop that sells these varieties exclusively purchase the seeds from Seminis? Thanks for your insight.

Micky –

It is unfortunate that a good deal of garden marketing is based in fear these days. In this case, the fear is around the Monsanto company which actually no longer exists (so buying Seminis seeds supports Bayer, not Monsanto). While there may be issues that cause individuals to questions some of their practices, most common are the use of genetic engineering and production of glyphosate. There’s acutally a pretty strong consensus that both are low risk to both humans and the environment when used appropriately (also glyphosate is now generic, so other companies produce it, too).

As for purchases supporting certain companies that release plants, plant patents last for 20 years. During this time the company has way more control over the plant and potential royalties. After this time, the company may still produce the plant but it is also possible for other companies to produce the plants. Lemon Boy tomato was released in 1984, so it is no longer under patent. Seminis would not be getting royalties for it and other companies could potentially have the ability to produce it.

This post provoked an interesting response that brings up issues worth considering on their own–thanks for doing that! I’d like to add that concerns over GMO crops and seeds perhaps should not be reduced to potential direct harm to humans through consumption. Let’s say we still don’t know for sure.

However, what we do know is that corporate control of seed (now estimated to be at around 40% in the US) is a direct threat to biodiversity. The future of food likely rests on farmers’ pivoting from one seed variety to another as growing conditions change (not just due to climate change but also due to human pressures on the natural environment like pollution, degradation of farm land, moving river water far from its source as we do in California and etc.). Even today (and certainly in the near future) farmers find that long trusted seed varieties aren’t doing as well so they look for (or breed) another variety that is more suited to changing conditions. Corporations, however, are not pursuing the preservation of seed varieties. Instead, their focus is on producing standardized varieties. This creates a loss of genetic variety. It is genetic variety that makes possible our ability to respond to new pest problems and breed new varieties to face new conditions. Additionally, when GM plants breed with wild relatives (look for articles on “creeping bentgrass” grown on golf courses) the crossbreeding can lead to uncontrolled growth of the GM population, thus maintaining the engineered gene while reducing the genetic diversity of wild relatives.

I don’t have all the answers, just my own experience as a grower and as a social scientist doing research on farming in a time of growing corporate control. Hopefully I am contributing to the discussion in a useful way!