It’s time for our Spring edition of People and Plants. This time we’ll be taking a look at the life and accomplishments of Asa Gray.

CC image

Asa Gray (November 18, 1810 – January 30, 1888), now considered the most important American botanist of the 19th century, had very humble beginnings. He was born in the back of his father’s tannery in Sauquoit, New York, the eldest of eight children. From childhood Asa was an avid reader. After completing grammar school in 1825 he attended the Fairfield Academy in Herkimer Co., New York and then went on to the Fairfield Medical College in 1826. It was then he began mounting botanical specimens. He got his medical degree and did eventually open a practise in Bridgewater, New York but never really “made a go of it”, he enjoyed botany much more. So much more that in the fall of 1831 he basically gave up his medical practise to devote more time to the study of plants.

By 1832 he was trading specimens with botanists not only in America but also in the Pacific Islands, Asia and Europe.

In early 1836 he became curator and librarian at the Lyceum of Natural History in New York, now called the New York Academy of Sciences, he resigned in 1837. In 1838 he took a position at the newly established University of Michigan as the Appointed Professor of Botany and Zoology. This position was the first devoted solely to botany at any educational institution in America. He was soon dispatched to Europe to purchase books to start the university’s library and for equipment, such as microscopes, to aid research. He spent a year traveling around Europe, visiting gardens and meeting important botanists of the day including William Hooker in Glasgow, Jospeh Descaisne in Paris, Stephan Endlicher in Vienna, and Augustin Pyramus de Candolle in Geneva. He returned to the USA in 1841.

Some trip, eh?

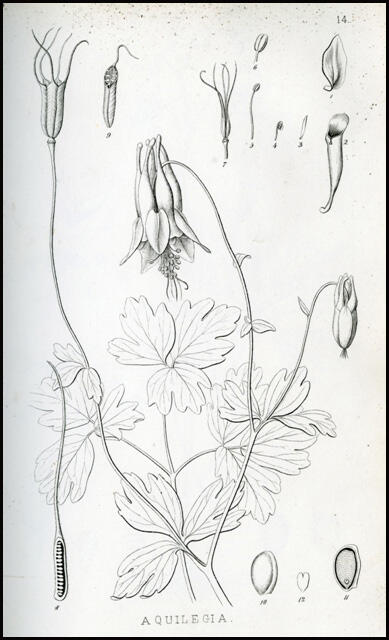

CC image

While he was in Paris at the Jardin des Plantes Gray came across an unnamed dried specimen, collected by André Michaux, and named it Shortia galacifolia. Over the next 38 years he spent considerable effort looking for a specimen in the wild. The first expedition in the summer of 1841 to an area in Ashe Co., North Carolina was unsuccessful. Further expeditions yielded the same negative results. In May 1877 a North Carolina herb collector found a plant he couldn’t identify. It was collected and sent to Joseph Whipple Congdon who contacted Gray telling him that he felt he’d found Shortia. Gray was thrilled to confirm this when he saw the specimen in October 1878. In spring 1879 Gray led an expedition to the spot where S. galacifolia had been found. Unfortunately, and much to his disappointment, Gray never saw the wild species in bloom.

CC image

In 1841 Gray was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. In 1842 he accepted the offer of a position at Harvard University. It included a salary of $1,000/year, teaching only botany, and being the superintendent of Harvard’s botanic garden. Though the salary was low the position allowed him plenty of time to do research and work in the garden. He was only 32.

At the time he had a priceless collection of more than 200,000 preserved plants, many of which he named as new species, and 2,000 botanical texts, which he donated to Harvard to found its botany department.

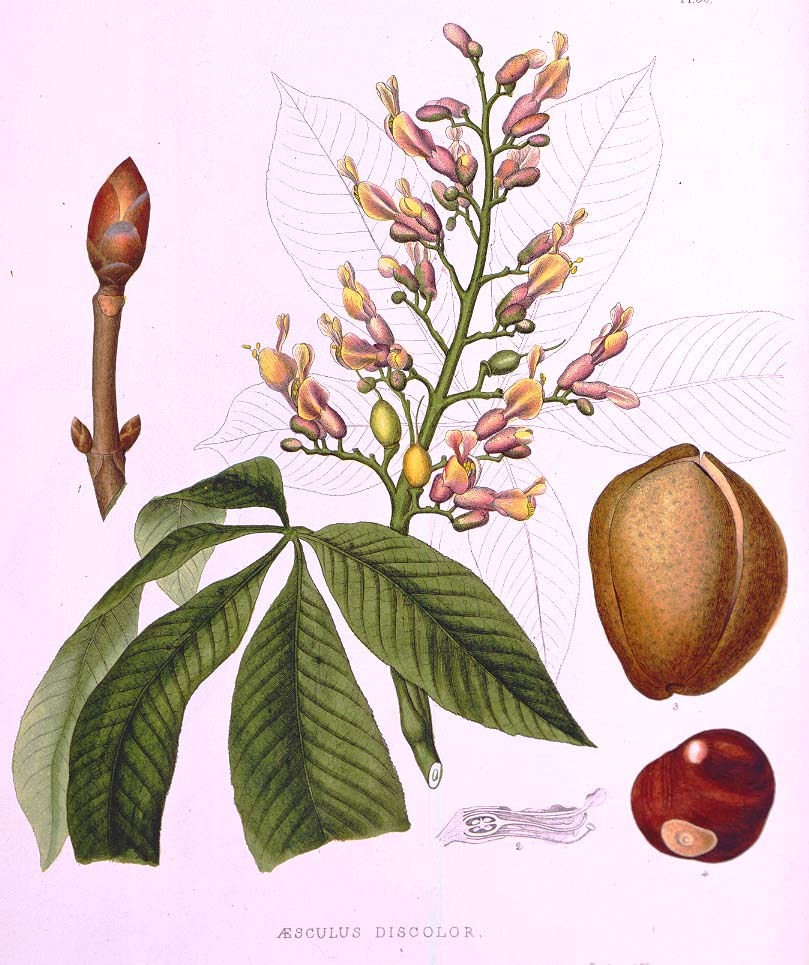

CC image

In the summer of 1844 Gray moved into what became known as the Asa Gray House in the Botanic Garden. As an academic, Gray was considered a weak lecturer but was highly regarded by his peers for his expert knowledge. He was better suited to teaching advanced rather than introductory classes, which he found tedious.

He eventually became well known by the outside of academia for his prolific writings and textbooks.

His first book, The Elements of Botany was published in 1836. In it Gray championed the idea that botany was useful not only to medicine, but also for farmers. His next work Flora of North America, co-authored with John Torrey, was published in 1938.

By the mid-1850s he had become so well-known that he wrote two high school-level texts in the late 1850s: First Lessons in Botany and Vegetable Physiology (1857) and How Plants Grow: A Simple Introduction to Structural Botany (1858). The publishers pressured Gray to make these two books non-technical enough so high school students and non-scientists could understand them.

A prolific writer, he was instrumental in unifying the taxonomy of North American plants. The most popular book was his Manual of the Botany of the Northern United States, from New England to Wisconsin and South to Ohio and Pennsylvania Inclusive, known today simply as Gray’s Manual. Gray was the sole author of the first five editions of the book and co-author of the sixth, with botanical illustrations by Isaac Sprague. Many editions have been published and it remains a standard in the field.

Gray also worked extensively on a phenomenon called the “Asa Gray disjunction” which is the surprising morphological similarities between many eastern Asian and eastern North American plants.

Before 1840 Gray’s knowledge of Western US plants was limited to specimens sent him by collectors and colleagues working in the field. He worked with George Engelmann, Ferdinand Lindheimer, and Charles Wright who all collected widely in the Southwest including Texas, New Mexico, and parts of northern Mexico.

Accompanied by his wife, Gray finally traveled to the American West on two separate occasions, the first by train in 1872 and then again in 1877. Both times his goal was botanical research and sample collection to take back to Harvard. His collecting companion on these trips was Jospeh Dalton Hooker, son of William Hooker whom Gray had met in Glasgow on his first trip to Europe in 1838. Gray’s and Hooker’s research was reported in their joint 1880 publication, “The Vegetation of the Rocky Mountain Region and a Comparison with that of Other Parts of the World,” which appeared in volume six of Hayden’s Bulletin of the United States Geological and Geophysical Survey of the Territories.

Asa died in January of 1888 after suffering a stroke two months prior.

Public domain image

We’ve just skipped a stone across the pond of Asa Gray’s life. Here are some links if you’d like to learn more.

Asa at 200 –https://huh.harvard.edu/book/asa-gray-200

The Asa Gray Bulletin – https://www.jstor.org/journal/asagraybull

Asa Gray: Faith and Evolution – https://sciencemeetsfaith.wordpress.com/2020/11/17/asa-gray-bridging-faith-and-evolution/

Asa Gray online papers – https://onlinebooks.library.upenn.edu/webbin/book/lookupname?key=Gray%2C%20Asa%2C%201810%2D1888

Asa Gray Award – https://www.aspt.net/asa-gray-award