The bee blogosphere (hiveosphere?) and listservs were abuzz the past two

days with news that Madison, Wisconsin, has taken an active role in

encouraging beekeeping within the city limits. The version of the

story I found a link to was in the Madison Commons.

Apparently beekeeping was prohibited in town (though the prohibition was

rarely enforced, except in the case of complaints). The ordinance was

changed to allow urban beekeepers to keep hives.

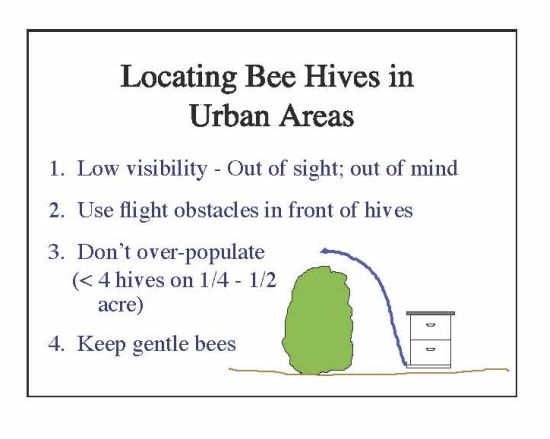

There are specific regulations, such as 25′ distance to the nearest

neighbor as well as a requirement to supply a fresh water source near

the bees (very important – especially in urban settings).

Flight barriers – fences, shrubbery, or sheds are also required. This

is a simple bit of beekeeping etiquette if you have close neighbors.

Bees will fly straight in and out of the hive entrance, usually just a

foot or two off the ground. They’ll maintain this altitude until

forced to go up or down. Constructing, planting, or placing the hives

in front of an existing barrier they must fly over ensures they will

maintain a higher altitude coming and going and not zip across your

neighbor’s lawn at kid-eyeball height.

I’m currently learning stuff like this and much, much more in the

brand-new Virginia Master Beekeeper Program, taught by the most

excellent Bee Professor on the planet, Dr. Rick Fell. Honeybee

physiology and sociology is absolutely astounding. I’ve been beekeeping

for four years now, and am just finding out with this class how much I

didn’t know. I was also unaware that incidences of beehive thievery are

at an all-time high, hence the out-of-site suggestion.

I’ll probably continue to pop out with the occasional post on bees,

because I just can’t curb my enthusiasm. "Cleansing flights" might be a

good topic…

Slide from Dr. Richard Fell’s immense bastion of knowledge.