Last year I talked about using cheap min-max thermometers to get a handle on the specifics of the micro climates in my garden, and I was reminded recently that I never followed up on what I actually found out, so that’s what I’m doing today.

Remember that these results are just ONE data point, specific information about conditions in my particular garden. Your conditions will probably be different, so don’t try and extrapolate from these to your garden. Instead, if you are curious about your micro-climates, get a few thermometers, scatter them around, and see what happens.

What I did:

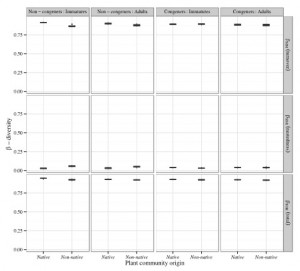

I placed thermometers three different locations – up in the air on the north side of a shed, on the ground out in the middle of an open area, and on the ground up against the south side of a shed. I expected the ground thermometers to be warmer, thanks to the insulation of snow, and the one on the south side of a shed to be warmer still, thanks to the added heat from the sun.

What I found

I was surprised on several fronts. First, the south side of the building was, for me, only warmer during the day. I recorded higher high temperatures, but at night, it dropped down exactly as cold as everywhere else. This may be partly because we have extremely cloudy winters here in Michigan, so there isn’t a whole lot of sun to warm up the south side of anything. The wall is also an unheated shed, so there was no extra heat leaking out from inside the way there would be up against the walls of a house, particularly if it is old and poorly insulated.

Ground level, under the snow, was as I expect warmer than the air temperature above. Much warmer than I had expected, in fact. We had about a foot or so of snow during the coldest part of the winter, and that snow kept thing more than 20 degrees F (~11 degrees C) warmer than the air temperature above the snow line. Keep in mind that the USDA hardiness zones are based on 10 degree F differences, so that thick layer of snow kept things almost two zones warmer. I knew snow was a good insulator, but I didn’t realize it would make that big a difference. Thank you Lake Michigan for all the frozen white stuff!

What I’m doing with the information:

I’m no longer trying to put tender plants against the south wall – Instead, I’m piling on a layer of mulch after the ground freezes to augment the insulating power of the snow. And given that south facing wall is much warmer during the day, I’m using it to grow heat loving plants that tend to pout in my cool, Michigan summers. Melons, peppers, and eggplant all adore the extra 5-10 degrees F (~2-5 degrees C) that south wall adds to my daily high temperatures.