We have about 3000 sq ft of mixed border surrounding (in multiple layers) our 1500 sq ft home. We take care of everything ourselves, in our spare time (ha!!). Thus, our maintenance schedule BARELY includes cutting back perennials and ornamental grasses Feb-March, plus any pruning needed for woodies…then some fits of weeding throughout the growing season.

Most of this stuff has been in the ground for five to eight years, and we have a high tolerance for nature taking its course. We’re surrounded by deciduous forest, so of course trees pop up where they’re not supposed to, especially oaks and the occasional hickory, which I dearly love and hate to remove. But I do. Because seedling trees are about impossible to just yank out like a weed – a whip just a few feet tall will have a taproot as long. With our stringent maintenance regime, they’re usually tall enough to poke up over the Panicum or loom over the Leucanthemum by the time I notice, so then digging becomes the only option.

Or, wait, maybe just cut it back really hard, like below the soil line. That’ll kill it, right? Nope? Back again? Chop, chop, hack, hack. Most saplings will give up after a few years. Except this one:

Ailanthus altissima a.k.a. “Tree of Heaven.”

Most of you know this is a totally invasive doody-head of a tree. Google for details if not familiar. I thankfully have not had much experience with it, until the past few years – there must be a mature one in the area. It would pop up here and there in our borders and blueberry field, but I didn’t think much of it. Grab the loppers, cut it back. BIG mistake.

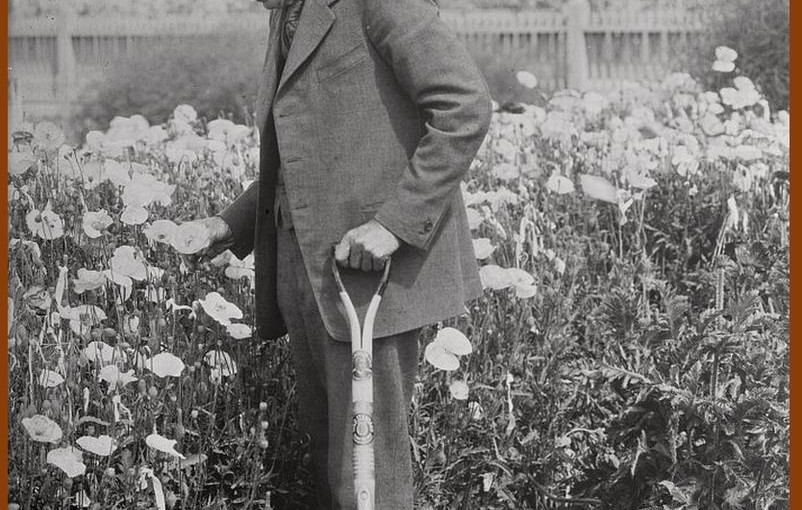

Behold, the most ridiculous root:shoot ratio ever:

Bunny, our pensive 40 lb whippet, for scale.

Bunny, our pensive 40 lb whippet, for scale.

I had lopped this individual back three years in a row. All I could see were the pale, unbranched shoots, not very imposing at all, so chop, chop. But finally, after a heroic effort last evening, it was successfully ripped from the heart of our main perennial border. Joel had to use our John Deere 950 tractor with a brush grabber chain to get this out of the ground, even after 20 minutes of his digging around the root to get the chain attached.

Like some kind of sea monster, my repeated attempts to kill it apparently just made it angry. And stronger.

It’s still out there, on our burn pile.

A dog barks in the night.

0_o.