One of the joys of working on a university campus is that construction never seems to end. As near as I can tell there are about 3,000 orange construction barrels that permanently reside on the MSU campus that simply get shuffled from one end of campus to the other every few months. Along with all the construction comes a never ending series of new landscape projects. Driving by one of the most recent projects the other day got me to thinking about the myth of Fall planting. In numerous extension bulletins and certainly in nursery sales advertising we hear that “fall is the perfect time to plant trees”.

Photo: Dana Ellison

The recent fall planting job on our campus gave me pause to think about this. I haven’t had a chance to completely survey the carnage but I suspect about a third of the trees will need to be replaced. Obviously there are lots of things that may have gone wrong here, irrespective of when the trees were planted and one exception doesn’t prove the rule. Nevertheless when I look back on the planting disasters I’ve been called in to inspect over the years a disproportional share (I’d say by a factor of two or three to one) are fall planting jobs.

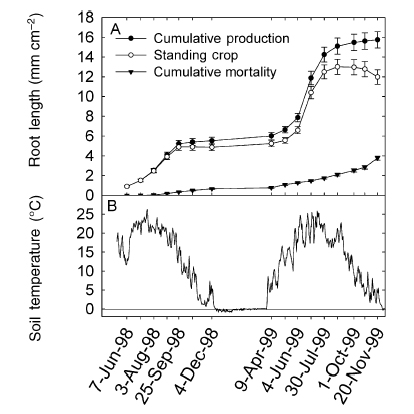

What gives? Well, the notion that fall is a great time for planting is built in a faulty premise, at least for this part of the country. Probably the most commonly cited reason for fall planting is that trees grow a lot of roots in the fall. This assumes that since there’s no shoot growth occurring, trees automatically shift reserves below-ground. There is certainly a ‘pecking order’ of carbohydrate distribution within a tree based on relatively strengths of sources and sinks. But there’s one factor that trumps all others: temperature. Soil temperature is the biggest driver of root growth. Measurements of new root growth in a cottonwood plantation in Wisconsin provide a classic example. As temperatures decline in the fall, new root growth essentially ceases. For trees that are well established, this is no problem. For trees that have just been transplanted and need to re-establish root-soil contact this is a tough row to hoe. Throw in a tough Michigan or Wisconsin winter and the tree’s facing an uphill climb.

New root growth of eastern cottonwood (top) and soil temperature (bottom). Source: Kern et al. 2004. Tree Phys. 24:651-660.

Again, most planting failures have multiple causal factors. Even if the trees on this site had been planted in the spring, they may have still experienced problems. My point is that a more accurate statement is “Fall is an OK time to plant trees”; not the ‘best’ time or even a ‘great’ time. I think these statements are often driven by the fact the fall is a slow time for nurseries and landscapers. When homeowners or landscapers ask me about fall planting the first thing I ask is if there is any reason why they can’t wait until spring, the real ‘best’ time for planting.

Bert, the Kern et al. article uses rooted cuttings planted in an unmulched field that was tilled and sprayed with herbicides. Furthermore, the roots were severed to decrease interference among trees. These are hardly conditions that are optimal for root growth.I see the unmulched conditions as being most detrimental to winter root growth, as mulching would have moderated both the high and low soil

620

temperatures as well as retained more water. In my review article on landscape mulches, I wrote “Root development and density

was greatest under organic mulches compared to that

under plastic, bare soil or living mulches.” There are so many factors in this experiment that are not “good practices” for installing landscape plants that I can’t see the connection to your advice not to plant in the fall. In the western part of the US, spring is second only to summer as the absolutely worst time to plant, since we get little to no summer rain. I’d be curious to see what the root systems of these pines look like once they’re excavated. Will you take photos and psot when you do the postmortem?

Excellent site, just wanted to point out that in certain parts of the country fall really is the way to go. I live in the mountains of Northern Arizona and have had wonderful success planting trees and shrubs in the fall. Spring is a horrible time to plant here, unfortunatly that is when the tree’s and shrubs are available in garden centers.

Ok, I have a thought. The real reason that fall planting is difficult is the quality of the garden stock at this time of year. Great sales, but the tree’s and shrubs have been growing in pots all summer and are completely root bound and horrible looking. I am just a humble home owner who loves trees and shrubs and man it can be difficult to find good stock in the

19e0

fall and early winter. Some of the sticks that I have recieved from mail order in the early winter have done the best for me by far. Just another thought on the hazards of fall planting. Thanks for your website, great info.

I have to agree with Bert. Fall is a great time to plant in the South (and the West too from what Linda says), but in the North drying winds CAN really mess up certain trees — particularly evergreens — which don’t have an established root system. Also, there are certain trees which just won’t transplant in the Fall — for example oaks and birch (I didn’t believe it until I tried a bunch myself).

When we lived in Buffalo we planted in the fall (and mulched well). No problems. I’d be really interested in seeing some experimental research comparing fall and spring planting, using bare-root stock, and proper landscape installation procedures, including mulch. (And as an aside to Joe – those root problems can be corrected at planting. You’re right – you can’t leave those circling masses of woody roots and expect the plants to survive.)

The photo seems to show the trees planted near an intersection and a sidewalk. Having gone to MSU myself, I can testify to the cold winters and heavy salt usage, especially at a school that has a policy to never close down for snow emergencies. A lot of my fall plantings in northern IL do not fair well along busy roads, and I think it is mostly the salt usage, and the lack of adequate watering by the residents (yes, we ask the residents to water the newly planted trees).

Also, the photo seems to show either that the trees were planted quite high, or were buried under soil and mulch. Any plans to excavate the dead ones and figure out the cause(s)?

Ok. I’ve been waiting for someone else to address this thought but I guess it’s going to come from me. I have been told for years and years that deciduous trees and shrubs should be planted in the fall. Conifers and most evergreens for that matter should be planted in the spring. Is this just local mid-atlantic culture lore? Or is there something to it? That guideline has always worked for me.

I’m with Linda — I’d like to see the root systems on those dead trees. For some reason, in the last few years I have had several evergreens (Douglas firs, white pines, arborvitae) come to my sites with puny little root masses for the size of the tree; the plants that don’t die outright (regardless of planting date) invariably suffer. I have also been taught that spring is the time to plant evergreens; my understanding was that in fall their relatively newly dug root systems — even if they would other wise be big enough to do so — can’t sustain them through the winterburn-inducing frozen soils and sun-warmed warm air of late winter.

I can understand that wind-induced desiccation of evergreens in very cold climates could put a strain on such trees planted in the fall. I’ll buy that as a reason not to fall-plant in very cold and windy climates. But soils mulched with thick layers of organic materials are unlikely to freeze hard (though in really cold climates I suppose they could – I’d like to see data on that too). Given the spotty failure in the landscape Bert posted, I am still doubtful it was climatic.

Just a comment on the ground freezing — we were working on a study where we wanted to dig trees out over this past winter — we didn’t expect to be able to but we figured we’d try. We were using a 6 inch mulch depth (wood chips) in a circle around trees with a radius of about two feet. After trying we determined that we had a frost line going at least six inches down — and we couldn’t pull out the trees (we ended up cutting them at the soil line). When I first came to Minnesota I was told that frost could go down three or four feet — I haven’t seen that yet, but a foot or even two feet isn’t strange at all.

So Jeff, are you telling me that all the fine roots die back in the winter to a 6 inch depth? Roots aren’t particularly cold hardy. I’m just trying to figure out how you have any woody plants at all!

Absolutely not — the roots handle it fine — different plants have different tolerances for “cold feet.” Black Spruce can handle about -10 degrees Celsius, some junipers are tougher than that. It’s also important to remember that, while the freeze depth is quite low here, the absolute low temperature that the roots experience once you get a few inches into the soil rarely gets below 28 degrees or so.

You’re right – 28F is not a hard freeze and roots can handle that fine. So playing devil’s advocate…why is it a problem to plant in the fall, if the roots can handle the cold soil? While they won’t grow when it’s that cold, they will grow any time the temperature warms up to 10C or so.

Hey Guys:

Was out in the field all day Tuesday. Just in for a couple of minutes. Couple of follow up notes to my post. Linda, I used Kern article as an example for a couple reasons. One, I had the figure handy since I use it in my Woody Plant Physiology lectures on factors controlling root growth. Plus, I’ve worked with one of the PI’s (Coleman) and have a lot of respect for Alex Friend and his contributions to our understanding of root physiology of trees, albeit largely form a forestry perspective. The basic point was to illustrate the overriding influence of temperature on root growth. I’m sure a post mortem will find some other issues with the trees. (as an aside, one of my pet peeves with post mortems is that we typically just look at the trees that died and rarely the trees that lived but that’s a post for another day) My point is that, in this part of the co

untry, the margin for error is smaller in the fall that in the spring. I realize this is anectodal and very un-Garden Professorial, but if I looked at 10 spring planting jobs around here I would probably find 2 will some substantial issues (substantial in this case meaning there may be some warranty re-planting invloved); a likely number for fall planting would probably be double that. There is no absolute with trees. On the whole, both fall and spring planting can be successful -and both can fail. But, other factors being equal, my experience is that the likelihood of success is better with spring planting than fall.

In terms of issues with climates with dry or hot summers, I think Mo makes a good point. If irrigation is available then spring planting makes sense. In most cases it’s easier to add water if things get dry than it to warm the soil in the late fall. If irrigation is not an option and if you have longer window of warm weather in the fall than we have here in the Upper Midwest, then fall planting may be a better option. A large portion of bare-root seedlings planted for reforestation in West are fall-planted for this reason. But for those of us in much of the rest of the country, I will stick to guns and recommend spring planting if there is no compelling reason to plant in the fall.

Does anyone factor irrigation, or lack thereof, in when the best time to plant is? I’ve always been under the assumption that if proper irrigation is provided, it’s hard to beat a spring to early summer planting here in VA. I guess you need to define what proper irrigation is. The typical reccomendations from local nurseries in this area is to start off with deep root soakings infrequently. A lot of times this seems to doom some people, either because they water too much or it’s not frequent enough. I’ve never had a problem with starting new plantings with light and frequent, perhaps every day at first. After a couple of weeks I tend to not let the rootball dry out. I think a big problem with urban landscapes is the “fire and forget” mentality that an area Extension agent has mentioned. People tend to think that with irrigation systems and other conveniences, including landscape maintenance contracts, they can forget about the plants, thinking that they’ll take care of themselves.

I’ve had the worst success with plantings in the fall, whether it is deciduous or evergreen, and whether or not myself or a customer planted it. I suspect a lot of that, at least for the customers, is due to the belief that they get plenty of root growth, despite moisture (fall months are our lowest average rainfall-wise) and temperature (which can be fairly mild). When they believe that, they are unlikely to irrigate the following spring and summer.

Mo, I think one of us GP’s (Jeff or Bert? or maybe it was one of my Washington colleagues) was discussing some new research that showed frequent, shallow watering is more useful than deep and infrequent. This makes perfect sense, given that most fine roots are in the upper few inches of soil and deep watering doesn’t do them much good.

It just goes to show that gardening advice is often regionally rather than universally true. In Seattle, where summers are as dry as the Sonoran Desert and winters are mild, fall IS a good time to plant. Some place with wetter summers and colder winters maybe not so much.

After planting many thousands of trees over more than thirty years in northern Virginia I have seen consistently poor results in planting evergreens mid October and later, but in particular Leyland cypress and cherry laurel varieties that are acknowledged as having weak roots. With Leylands B&B and container grown plants have fall planting problems, so the problem is more than just from the digging. I don’t have the answer why, but I am confident enough in this observation that I discourage clients from planting late in the season, even if it costs me a sale, rather than having the tree die through the winter.

Linda,

Must’ve been Jeff. I’ve still been toeing the company line that deeper, infequent watering is better, especially when turf is involved. But I can be persuaded by quality research!

I’m pretty sure it wasn’t me either — In general I believe in deep, less frequent too — but, like Bert, I can be convinced otherwise.

It’s extraordinary that in 2010 we’re still debating these seemingly fundamental landscape horticulture-related questions!

Maybe the four of you could get funding (about eleven months until the next round of HRI proposals are due) to confirm seasonal fluctuations in soil temperatures in a range of typical landscape planting sites; e.g., open lawn, parking lot planter, tree lawn, foundation landscape bed by mulched and unmulched. Using I-Button-like data loggers placed at various depths in vertically –oriented PVC pipe “inspection tubes,” collecting this data need not be terribly expensive.

A second phase of the project could be to plant a range of common/popular landscape species that thrive in all of your locations (e.g., burning bush, Chinese juniper, Norway maple, white pine, river birch, etc.) in each of the above settings. These species would be established in B&B, container-grown and bare root form and, of course, planted in spring (April), summer (July), and fall (early September).

What could make this project groundbreaking is that you could incorporate this blog into the project as a means of communicating in real-time the practice and observations associated with well-executed science!

This could allow you to explore the effectiveness of interactive Internet technology in the widespread, instantaneous dissemination of research-based information to both multiplier and end-user audiences.

It can also provide an example of how interactive Internet technology can help in the identification, confirmation, and maybe even financial/in-kind support for high-priority needs of the landscape horticulture industry?

What?! You mean quit arguing about things and actually DO something?!

Just kidding! Great idea Terry. I really like the notion of the ‘real-time’ dissemination of results via the blog. Hmmmm… I wonder if reader posts count as peer review…

A few quick comments: Terry, there are literally hundreds of articles documenting that mulches keep soils warmer in the winter and cooler in the summer. I don’t think anyone still debates that point. Bert and Jeff, my information came from a recent article in Arboriculture and Urban Forestry. Of course, I’ve left my hard copy at work and the website isn’t letting me access the electronic copy. Hopefully the latter issue will be fixed and I can add to this discussion tomorrow…

You’re correct (since you’re written the most recent definitive review of the influence of mulches in landscape settings), Linda, regarding the moderating effect of mulch on soil temperatures (and moisture).

My interest is more in documenting the specific seasonal fluctuation of soil temperatures in a range of landscape settings across a broad geographical area. This, I think, would get at the issue of the validity (or lack, thereof) of broad brushstroke recommendations used to paint the implementatio

n of landscape practices across the entire continent.

Meanwhile, as to your comment regarding peer review, Bert, I’m not suggesting the comments on a blog replace that principle component of the practice of good science. Rather, it would be the experimentally designed study of the effectiveness/influence of real-time dissemination of research-based information via the blog that would be peer reviewed.

What I’m trying to say is that the four of you are already doing something extraordinarily unique in the more than one hundred year-old field of applied horticulture research/ extension. Why not incorporate and scientifically measure this effort as part of a complex, continent-spanning study designed to answer some of the seemingly basic questions the four (and the entire landscape horticulture industry) can’t seem to agree upon?

Terry, like Bert I think you have a great idea. Unfortunately, the reality is that few agencies fund this kind of research. USDA funds food and fiber research. There are some groups (like ISA) that fund small studies, but until federal agencies decide that urban horticulture and nonfood gardening are important, we won’t have the resources we need. I know this sounds like a cop-out, but this kind of work requires graduate student help (for which we would pay tuition, fees and salary for 1-3 years) in addition to other costs. I’m open to strategizing how to do this, especially because I’m situated at a research center with acres and acres of land that could be used for such a study.

O.K., so maybe this is how such a study begins – outlining for all the world to see how (landscape horticulture) science does/doesn’t get funded?

For example, an MS student costs somewhere between $50,000 and $75,000 per year, depending upon the institution, for salary, tuition, benefits, etc., correct? Then there’s somewhere around 50% for institutional overhead (to cover the maintenance of the acres and acres of land at your research station, electricity, telephone, fixing leaking roofs, research technician salaries and benefits, computer networks, irrigation systems, etc.). And, we’ve yet to talk about money for plant materials, equipment, fertilizer, travel costs to present findings at conferences, etc., etc., etc.

So, to fully fund one year of well-designed landscape horticulture research in the field it costs somewhere between $100,000 and $150,000, correct?

Then, times four locations, we’re looking at close to $500,000 per year!

Hmmmmm, no wonder the definitive answers to these seemingly simple questions are so elusive!

Obviously, the HRI (Horticulture Research Institute) doesn’t have this kind of money.

So, what about sources that fund green infrastructure projects? Or, what about exploring funding through the NSF Informal Science Education (ISE) “Communicating Research to Public Audiences” program? And, what other types of non-horticulture funding opportunities might exist by collaborating with colleagues in your institution’s schools/departments of education, information studies, etc.?

And, of course, what kind of in-kind services, materials, etc. could be obtained from the industry in each location?

Thoughts?