Not much activity on the Friday quiz! It was a tricky one. Take a look at our photos in total:

As you can see, these aren’t plant “problems” in the strictest sense. (The “landscape” in question is a retail nursery.) They are cultivated anomalies – little mutations that have been discovered and propagated. There are several points to this exercise:

1) Be sure you know your plant material! Many peope mistakenly assume that plants such as these are diseased, pest-ridden, or lacking some nutrient and need to be “fixed.” Personally, I don’t care for yellow cultivars; like Lisa B and Deb, I think they look chlorotic. Without identifying tags, though , it would be hard to know these are not deficient in nitrogen or some other macronutrient. I guess I would wait until leaves emerge in the spring: if they were yellow then and stayed yellow, I would presume the plant was a yellow cultivar.

2) Many of these cultivars are not particularly vigorous. A plant that’s missing much of its foliar chlorophyll does not photosynthesize efficiently and would probably not survive in nature. In our managed landscapes, however, we can nurture these oddities so they aren’t out-competed by other plants.

3) Cultivars such as these often revert to the wild form (remember Bert’s quiz last week?). The natural form (green vs. yellow leaves, or normal vs. dwarf stature, for example) is nearly always more vigrous than the mutation, and given the opportunity plants will outgrow these limitations. Thus, many cultivars require careful maintenance to remove “sports” before they overtake the plant.

Chlorotic, shmlorotic: I adore that Choysia! Just took some cutting from a friend’s garden (prior to frost)which are now happily rooting. I loathe the Euonymous,though, for absolutely no good reason.

You see, that’s what happens when you’re a physiologist. You can’t look at an unusual plant without wondering what’s wrong with it…

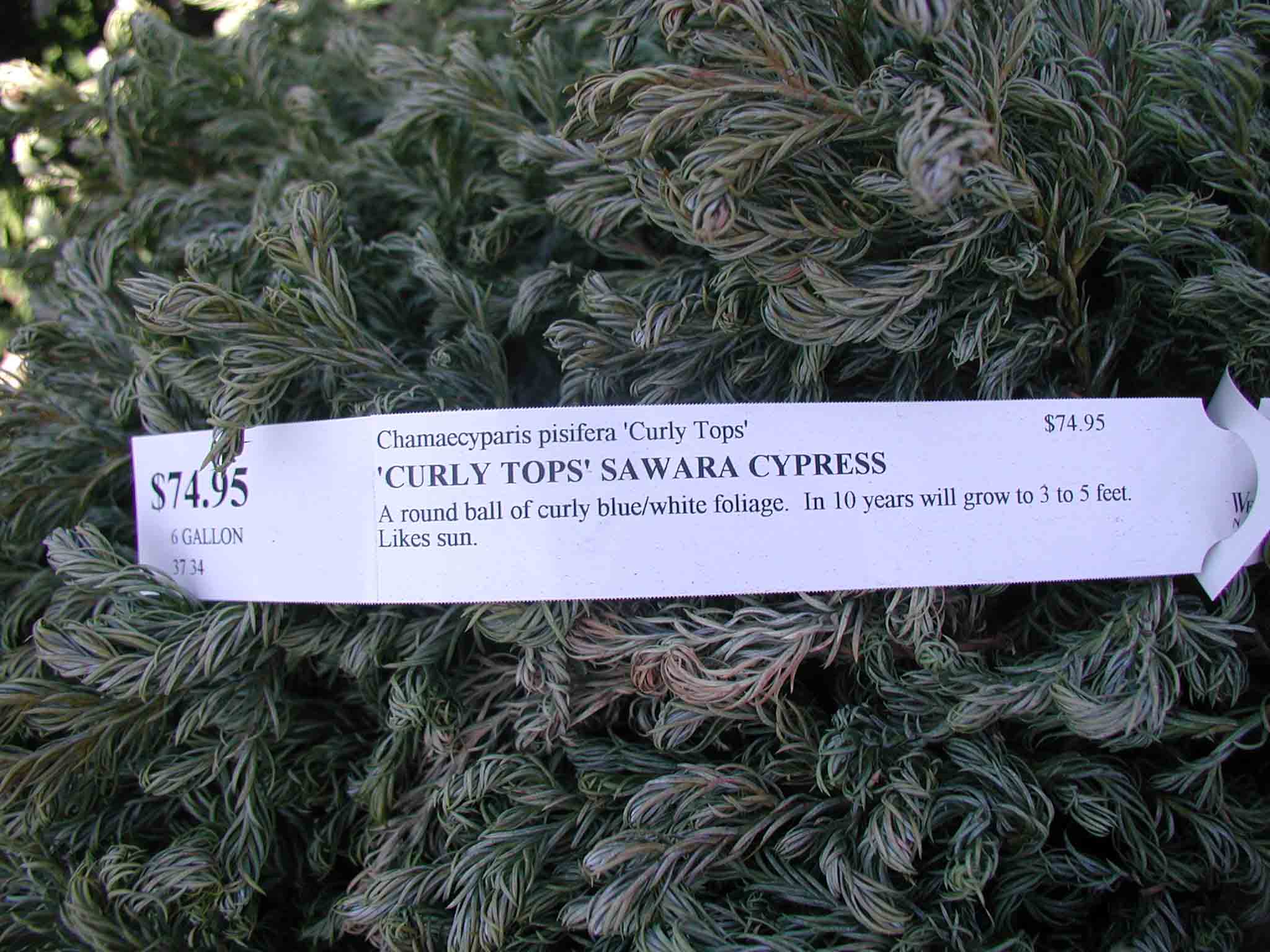

Well, dadblammit — good quiz! I still say that Curlytops Sawara Cypress looks like it has been zapped with something bad; guess that’s why I don’t specify them…

I think it is misleading to include Choisya ternata ‘Sundance’ in this quiz as an example of a plant that doesn’t have enough chlorophyll compared to the normal green form. Firstly, because the chartreuse coloration is only on the newest foliage and then turns the normal green color as it ages. In my opinion, this contrast between new and old foliage is what makes this cultivar so attractive. The fact that the color change comes in mid winter to early spring and then fades to normal also lends to its use as a seasonal accent that doesn’t overstay its welcome in the garden year round. Secondly, this cultivar is not a weak grower here in northern California, and seems to do just as well in landscape situations as

the normal form. I can understand if one just doesn’t like the look of yellowish foliage, but if you call it chartreuse instead, I bet it is instantly more attractive to many gardeners. I’d say that other foliage plants with similar characteristics, such as Coleonema pulchrum ‘Sunset Gold’, Sedum ‘Angelina’ and Cotinus coggygria ‘Grace’ are similarly useful in some applications. All look good where they can light up a dark spot in a garden, or provide a good foliage contrast with other shades of green, especially when used as an accent to direct the view across a garden.

Also, isn’t a brighter foliage color a benefit in climates where it is overcast so much of the winter? Sometimes one’s biases can get in the way of appreciating the design potential of certain plants…

Bahia, I wasn’t trying to promote a particular aesthetic – many people like these variants. My point was that in natural communities these plants don’t compete very well with other plants because they don’t photosynthesize as efficiently. And because some of these cultivars have odd-looking foliage, they can easily be misdiagnosed as diseased or nutrient deficient.