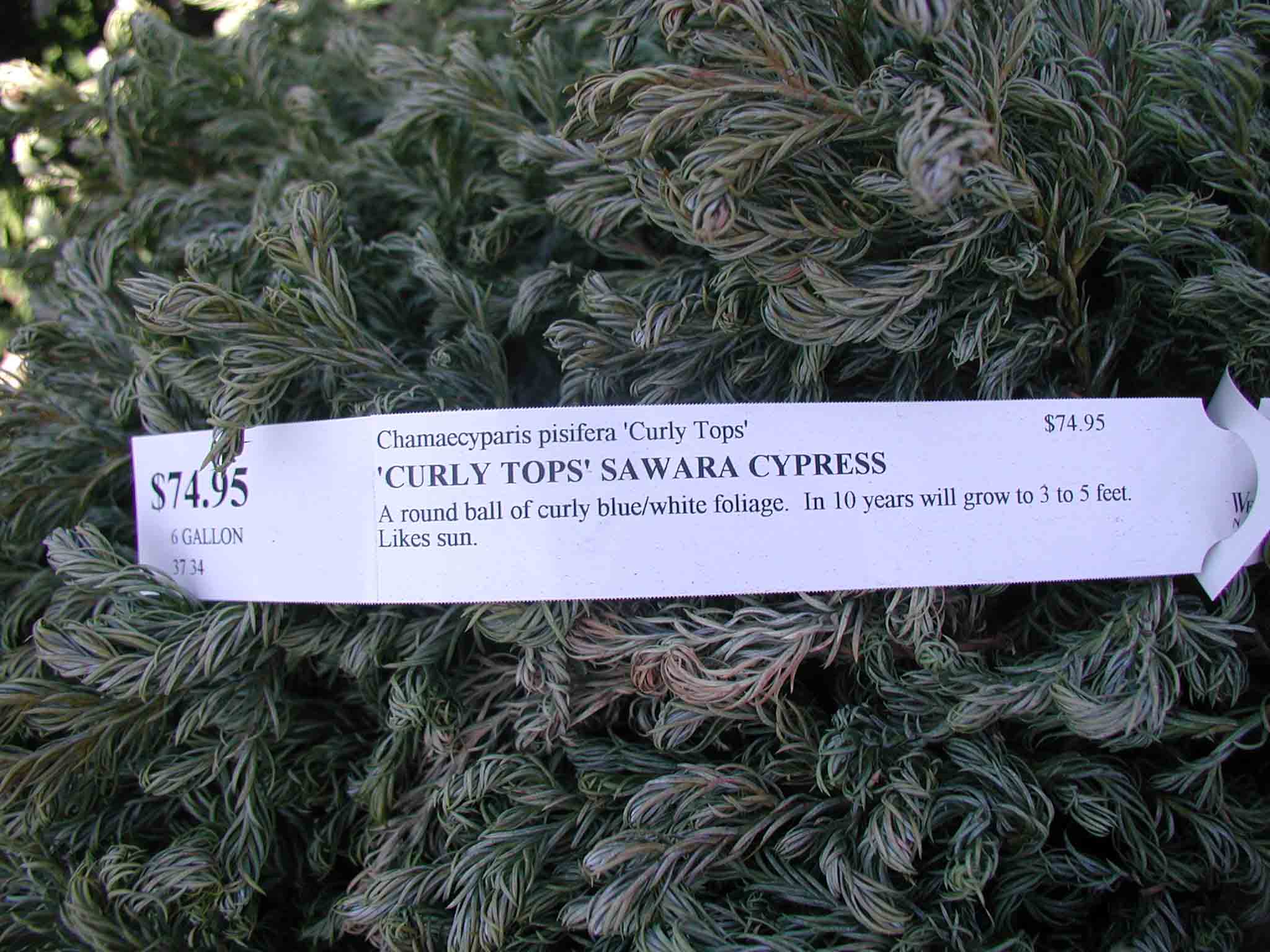

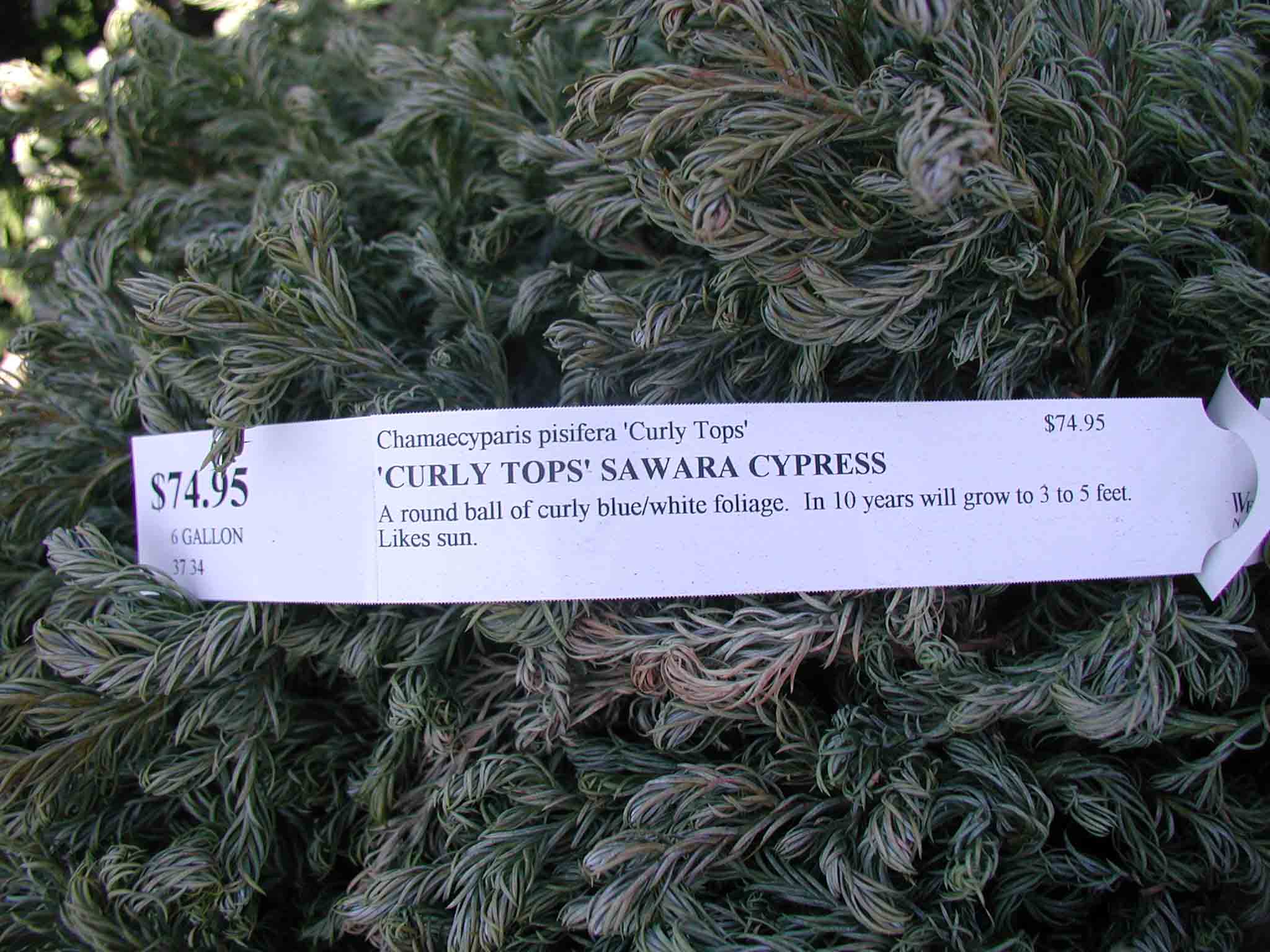

Not much activity on the Friday quiz! It was a tricky one. Take a look at our photos in total:

As you can see, these aren’t plant “problems” in the strictest sense. (The “landscape” in question is a retail nursery.) They are cultivated anomalies – little mutations that have been discovered and propagated. There are several points to this exercise:

1) Be sure you know your plant material! Many peope mistakenly assume that plants such as these are diseased, pest-ridden, or lacking some nutrient and need to be “fixed.” Personally, I don’t care for yellow cultivars; like Lisa B and Deb, I think they look chlorotic. Without identifying tags, though , it would be hard to know these are not deficient in nitrogen or some other macronutrient. I guess I would wait until leaves emerge in the spring: if they were yellow then and stayed yellow, I would presume the plant was a yellow cultivar.

2) Many of these cultivars are not particularly vigorous. A plant that’s missing much of its foliar chlorophyll does not photosynthesize efficiently and would probably not survive in nature. In our managed landscapes, however, we can nurture these oddities so they aren’t out-competed by other plants.

3) Cultivars such as these often revert to the wild form (remember Bert’s quiz last week?). The natural form (green vs. yellow leaves, or normal vs. dwarf stature, for example) is nearly always more vigrous than the mutation, and given the opportunity plants will outgrow these limitations. Thus, many cultivars require careful maintenance to remove “sports” before they overtake the plant.