As we hurdle ever closer to the holidays and the end of the year, there’s lots of plants we could talk about – amaryllis, poinsettias (and the abuse thereof with glitter and paint), whether or not your cactus celebrates Thanksgiving, Christmas, Easter or is agnostic, and on and on. Each of these plants have an interesting history and connection to the holidays, but today we’re going to be a little more naughty…but nice. We’re going to talk about mistletoe.

Now, mistletoe is one of those holiday plants that you don’t really want growing in your own garden. That’s because, even though it is a symbol of love and even peace, it truly is a parasite … and poisonous. It has been celebrated and even worshipped for centuries, and still has a “naughty but nice” place in holiday celebrations.

Burl Ives, as the loveable, banjo-playing, umbrella-toting and story-narrating snowman in the classic “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” claymation cartoon tells us that one of the secrets to a “Holly Jolly Christmas” is the “mistletoe hung where you can see.” But where does this tradition of giving someone an innocent (or not-so-innocent) peck on the cheek whenever you find yourselves beneath the mistletoe come from? And just what is mistletoe anyway?

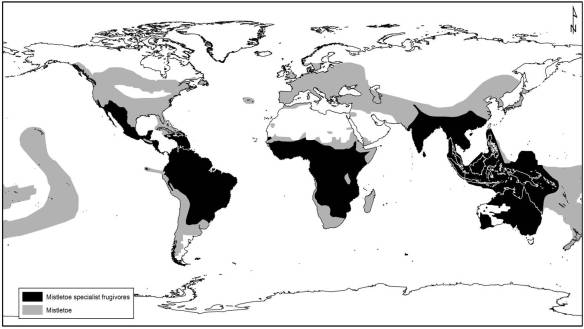

There are around 1500 species of mistletoe around the world, mainly in tropical and warmer climates, distributed on every continent except Antarctica. In North America, the majority of mistletoe grows in the warmer southern states and Mexico, but some species can be found in the northern US and Canada. A wide variety of birds feed on the berries of mistletoe and thus disperse seeds. These birds include generalists who opportunistically feed on mistletoe, and specialists who rely on the berries as a major food source.

First, we’ll cover the not-so-romantic bits of this little plant. Mistletoe is a parasitic plant that grows in a variety of tree species by sinking root-like structures called haustoria into the branches of its host trees to obtain nutrients and nourishment. It provides nothing in return to the tree, which is why it is considered a parasite.

Mistletoe grows and spreads relatively slowly, so it typically does not pose an immediate risk to most trees. While a few small colonies of mistletoe may not cause problems, trees with heavy infestations of mistletoe could have reduced vigor, stunting, or susceptibility to other issues like disease, drought, and heat. So be on the lookout for mistletoe in your trees and monitor it’s progression.

This little plant does have a long and storied history — from Norse mythology, to the Druids, and then finally European Christmas celebrations. Perhaps one of the most interesting things about the plant is the name. While there are varying sources for the name, the most generally accepted (and funniest) origin is German “mist” (dung) and “tang” (branch). A rough translation, then, would be “poop on a stick,” which comes from the fact that the plants are spread from tree to tree through seeds in bird droppings.

In Norse mythology, the goddess Frigga (or Fricka for fans of Wagner’s operas) was an overprotective mother who made every object on Earth promise not to hurt her son, Baldr. She, of course, overlooked mistletoe because it was too small and young to do any harm. Finding this out, the trickster god Loki made a spear from mistletoe and gave it to Baldr’s blind brother Hod and tricked him into throwing it at Baldr (it was apparently a pastime to bounce objects off of Baldr, since he couldn’t be hurt).

Baldr, of course, died and Frigga was devastated. The white berries of the mistletoe are said to represent her tears, and as a memorial to her son she declared that the plant should represent love and that no harm should befall anyone standing beneath its branches.

The ancient Druids also held mistletoe in high esteem, so high that it could almost be called worship. During winter solstice celebrations, the Druids would harvest mistletoe from oak trees (which is rare — oak is not a common tree to see mistletoe in) using a golden sickle. The sprigs of mistletoe, which were not allowed to touch the ground, would then be distributed for people to hang above their doorways to ward off evil spirits.

While the collecting and displaying of mistletoe was likely incorporated into celebrations when Christmas became widespread in Europe in the third century, we don’t really see mention of it used specifically as a Christmas decoration until the 17th century. Custom dictates that mistletoe be hung in the home on Christmas Eve to protect the home, where it can stay until the next Christmas Eve or be removed on Candlemas (which is Feb. 2). The custom of kissing beneath the parasitic plant isn’t seen as part of the celebration until a century later.

Washington Irving, who more or less reinvigorated the celebration of Christmas in the United States in his day and whose writings still define the idyllic American Christmas celebration, reminisced quite humorously about mistletoe and Christmas from his travels to England. He wrote:

“Here were kept up the old games … [and] the Yule log and Christmas candle were regularly burnt, and the mistletoe with its white berries hung up, to the imminent peril of all the pretty housemaids.”

Whether or not your housemaids will be in peril, the hanging of the mistletoe can be a fun Christmas tradition. Look for it at garden centers and Christmas tree lots this season. Or maybe you can find some growing wild and harvest it for your own decor. However, I would recommend not getting it out of the trees the “old Southern way” — shooting it out with a shotgun.

Sources:

- Tainter, F.H. (2002). What Does Mistletoe Have To Do With Christmas? APSnet Features. Online. doi: 10.1094/APSnetFeature-2002-1202

- Briggs, J. (2000). What is Mistletoe? The Mistletoe Pages – Biology. Online. http://mistletoe.org.uk/homewp/

- Watson, DM. (n.d.) (accessed). Mistletoe Seed Disperal [Blog Post]. Retrieved from https://ecosystemunraveller.com/connectivity/ecology-of-parasitic-plants/mistletoe-seed-dispersal/

- Norse Mythology for Smart People. (nd) The Death of Baldur. Retrieved from https://norse-mythology.org/tales/the-death-of-baldur/