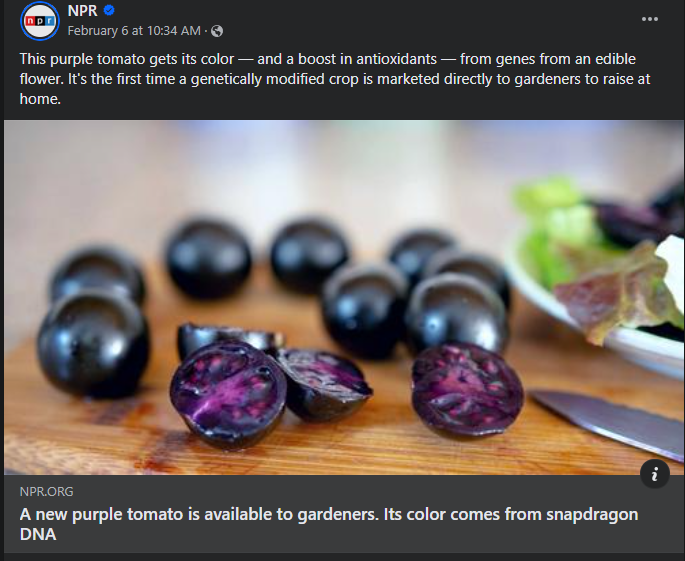

A few months ago I wrote about the newly released Purple Tomato, one of the first direct-to-consumer genetically engineered plants made available to the general public. (I’m happy to report that my Purple Tomato seedlings are growing along quite well.) Shortly after I wrote that article, I learned about another new genetically engineered plant being released to home gardeners, this time a bioluminescent petunia. So, of course you know I just had to have some.

The Firefly Petunia was released recently from Light Bio, a company based in Idaho. The company states that they grew out 50,000 plants for initial sale, but have worked with third-party growers to grow out additional plants from cuttings due to high demand for the plants.

The petunia itself is pretty nondescript. It is a small-flowered, white variety that wouldn’t get a second glance at a garden center. But the company introduced a set of genes from a bioluminescent mushroom called Neonothopanus nambi that make the faster growing parts of the plants (mainly flowers, but also other growing points) glow. The glowing is caused by a reaction between enzymes and a class of chemicals called, funnily enough, luciferins. And this is bioluminescence – it glows all the time in the dark. It isn’t like a “glow in the dark” where they have to charge up with a light source and only glow for so long.

Just like the petunia, the fungus is pretty nondescript during the daytime, but glows brightly once darkness descends. I’ve seen glowing fungus once in my life. As a kid I once saw what is called Foxfire, a glowing fungus on some decaying logs. It is pretty cool seeing something glowing so eerily in nature. Now, I have that same glow in my garden.

Back to the plants. The plants are a bit of investment, ringing in at $29 per plant plus shipping, but there are some price breaks at higher quantities if you order several or put together a group order. As a startup, I suppose the company is banking on the novelty of the plant to demand such a high price to cover costs. According to several sources, these white petunias are just the start. They’re working on roses, houseplants and more.

But why glowing petunias?

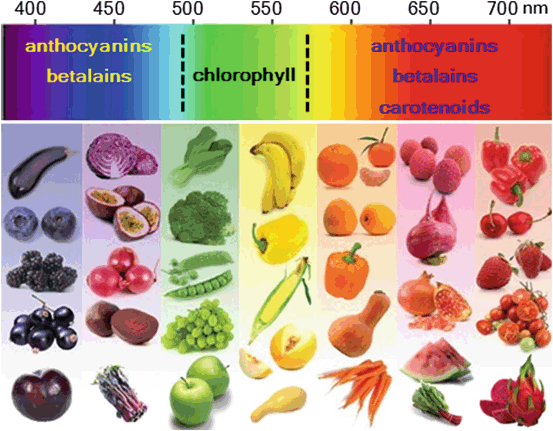

Before I placed my order, I had to take a step back and think about why. Why a glowing petunia? With the tomato there is at least the case of increased health properties with added anthocyanins. But what is a value of a glowing petunia other than a novelty? Is there a purpose? Or is it just hubris? And why are there genetically engineered plants on the market all of a sudden?

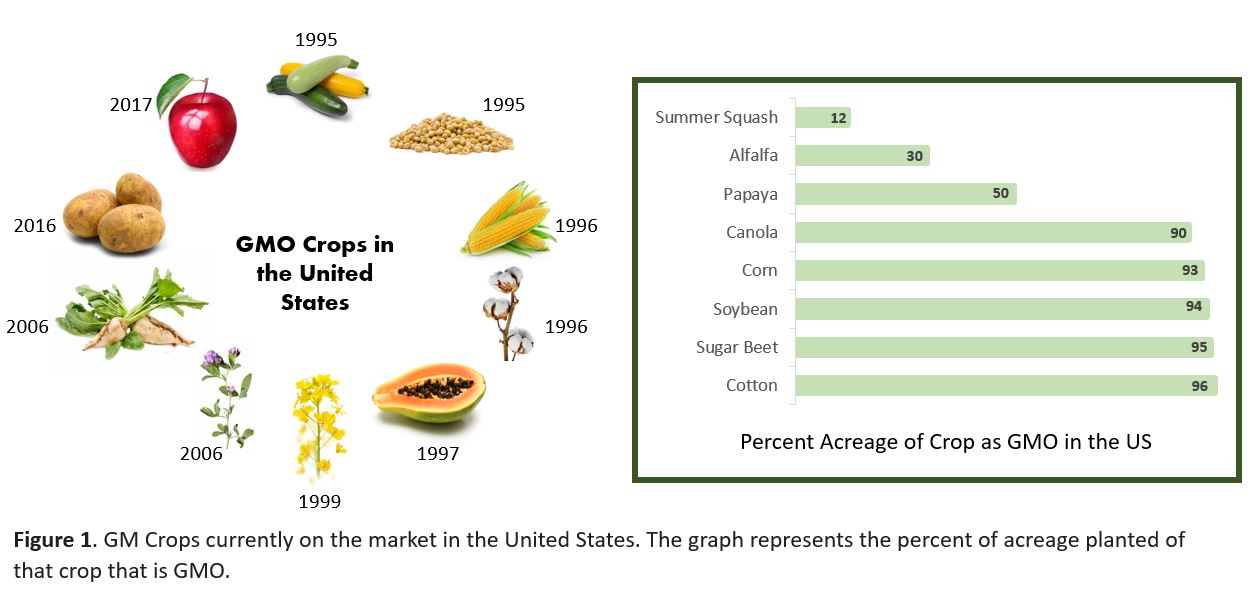

While the petunias don’t have a culinary or health value, the value that they bring is one of acceptance and familiarity. For decades now, well organized and funded campaigns have spread fear of genetic engineering. Seed companies embraced “Non-GMO” as a marketing scare tactic to drive up sales due to a fake boogie man. And even bottled water and salt are labeled as “Non-GMO”. But it seems that the tide of public opinion seems like it might be turning.

Seeing the excitement around both the Purple Tomato and this bioluminescent petunia seems to show a growing interest, or at least a waning of distrust, in genetically engineered plants. And It think that is one of the benefits, or maybe the causes, of seeing genetically engineered plants on the market. Researchers have found that the online conversation about genetically engineered organisms seems to be shifting – from less polarized to increasingly favorable.

While there are sill some hiccups and some ethical and environmental issues, most scientists see genetic engineering as the most important tool in addressing issues such as endemic plant diseases affecting staple crops and developing plants that can withstand warmer and drier conditions as the climate changes. In order for us to be able to fully use these tools, the conversation needs to continue to shift to a more favorable position.

Starting off with tomatoes, petunias, and other flowers is also a choice of ease. Growing plants that don’t have native counterparts where there could be unintentional spread of genes in the wild reduces some of the regulatory hurdles plants face in the United States. And while the purple genes introduced into tomatoes could spread to plants in the food supply, the safety risk is minimal. It would be much harder to get approval for, say, a genetically engineered sunflower or coneflower where there are wild-growing natives into which the glowing genes could inadvertently spread.

Why are genetically engineered plants popping up all of a sudden?

Probably one of the reasons we are seeing so many new genetic engineering projects now is that it is so much easier. With the discovery of CRISPR-Cas9 technology, it is much easier for scientists to transform plants with DNA insertions or extractions. This technology has revolutionized the world of genetics and genetic engineering not only in the plant world, but also in the areas of human health and more.

Before CRISPR, there were a few methods of introducing DNA into organisms. The most common one for plants was probably using a plasmid from the bacterium Agrobacterium tumefasciens. This is the cause of crown gall and it works by inserting its own ring of DNA, called a plasmid, into the DNA of the plant. The plant then produces proteins based on the virulent DNA and also replicates the DNA. One of the common method was bombardment, putting the DNA on tiny microscopic beads, usually gold, and shooting them into the tissue. Tobacco mosaic virus was also used for plant genetic transformations, especially in related plants such as tobacco, tomato, and…..petunia. Most of the work I did in undergrad was with the commonly used with model plant Arabidopsis thaliana (mouse-ear cress).

The transformation, or success, rates for these methods was relatively low compared to CRISPR. Plus, where the DNA ended up was random. There was no control over where the new snippets of DNA ended up, or what genes they would disrupt, or knock-out, in the process. I did quite a bit of research as an undergrad on figuring out just what genes were knocked out in certain transformations and what that changed in their physiology or response to stimuli (our research focus was gravitropism and response to red light).

CRISPR has taken away the guessing game from genetic transformations. Scientists can now target exactly where they want genes to be inserted, or in some cases “knocked out” or interrupted so they are not expressed. For example, Arctic Apples were developed by knocking out the gene in apples that makes polyphenol oxidase, the enzyme that causes them to turn brown after cutting. This has created a technology that has the potential to substantially reduce food waste in crops that have similar reactions as well, such as potato.

So I think the trend of genetically engineered plants for consumers will continue to grow. Evolving from novelty plants to plants that serve a higher purposes, such as nutritional value enhancements, climate change resistance, and more. It will take us a while to get there, but as the technology advances so does, it seems, public opinion. Until then, I’ll just enjoy my glowing petunias and purple tomatoes.

Additional Sources

https://www.science.org/content/article/mushrooms-give-plants-green-light-glow

https://www.fastcompany.com/91073850/glow-in-the-dark-petunias-are-just-the-beginning

Asian Delight Pak Choi

Asian Delight Pak Choi

Pepper Habanero Roulette

Pepper Habanero Roulette

Eggplant Patio Baby

Eggplant Patio Baby