If you listen closely you can hear the beasties in your garden just a-singin’ that tune. And who can blame them? Warm temperatures and lush green gardens? They enjoy them as much as we do. But sometimes they can be enjoying our landscape a little too much. So now what do you do?

Visit the garden chemicals section at your local big box store?

Reach for your favorite “natural” or DIY concoction?

Ask your neighbor?

What is the best way to deal with the problem?

Three letters answer that question.

IPM.

What is IPM? Integrated Pest Management (IPM) is the management approach you should use to solve pest problems. It can manage all sorts of pests with minimal risks to people, pets, and the environment. IPM’s emphasis is on the management of problems rather than eradication. It focuses on long-term prevention of pests or their damage by managing the ecosystem.

IPM is a five step process: 1) correct pest ID, 2) monitoring and assessing pest numbers and damage, 3) pest ID guidelines for when management action is needed, 4) preventing pest problems, and 5) determining correct control measures. Let’s take a look at each one.

#1. Pest ID

Correct ID of the problem-causing critter is the most important aspect of IPM. If you don’t know what you’re dealing with, how can you devise an effective control strategy, if indeed one is needed?

So what is a pest? Pests are organisms which damage or interfere with desirable plants or damage structures. Pests also include organisms that can impact human or animal health. Pests may transmit disease or may be just a nuisance. A pest can be a plant (weed), vertebrate (bird, rodent, or other mammal), invertebrate (insect, tick, mite, or snail), nematode, or a pathogen (bacteria, virus, or fungus).

A correct ID of the pest must be made before deciding if control is needed. If you aren’t sure you’ve ID’ed it correctly or want a second opinion, take a sample to your local Cooperative Extension Service Office.

Note: Be careful about asking for pest ID at a garden center. Employees may not be knowledgable, or your request might be seen as a sales opportunity. And think twice before taking the advice of someone who might try to sell you something.

#2. Monitoring and Assessing Pest Numbers and Damage.

You’ve probably heard the saying, “The best fertilizer is the gardener’s shadow.” I’ll make the claim that “The best pest control method is the gardener’s shadow”.

For effective monitoring, you need to be out in your garden on a regular basis. Looking, listening, even handling plants, checking under leaves, etc., so you come to know it as well as you know the layout of your living room. You should have a good knowledge of your landscape’s microclimates, soil conditions, the path of sunlight through the year, how seasonal changes affect your garden and a general grasp of the climate. Once you know what’s “normal” for your landscape it’ll be easier to spot any abnormalities.

For example:

Your favorite rose always has a few aphids but the population seems to have exploded in the last few days. And why do some of them have wings?

Is that slug damage on that hosta?

You don’t recall seeing those rusty patches on that hollyhock before.

What are the odd black spots on this pomegranate?

Hmm….

Always ask yourself how extensive the damage is. Does it threaten the health or life of the plant, or is it largely cosmetic? Do you need more expert advice?

Continual monitoring and assessing of what’s going on in your landscape can help you decide if the damage is important or extensive enough to require pest management.

#3. Pest ID Guidelines to Determine if Management Action is Needed

Using the biological information of the correctly ID’ed pest will help you decide if you need to deal with the situation. Here are some things to consider when deciding if management is needed.

Is the pest short-lived and is only in the garden for a few weeks or even days?

Does it only make a seasonal appearance?

Is the damage of long duration/the entire growing season, only for a short time and the plant recovers, or is the damage mostly cosmetic?

Is it a pathogen?

Does it carry a pathogen?

Can it cause irreparable harm?

Is it an invasive species that can or should be controlled?

Does it threaten a needed food garden?

Is the damage really that bad?

Knowing the life cycle and feeding habits of your ID’ed pest will help you determine if control is necessary. Use their biology against them. Do your homework.

So you have a plant issue and you’ve correctly ID’ed the pest and the problem. It needs to be dealt with.

What’s your next step?

“Once in a Lifetime“

by the Talking Heads

#4. Preventing Pest Problems

“An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” applies to landscapes as well our personal health.

Ask yourself if the garden problems you’re facing, most of which will be cultural, can be handled with preventative measures.

Are you over or under watering? This stresses plants which can attract pests.

Is the plant that is under attack in a less than optimal location? Can you move it or change its environment to help it become healthier? Or should you just remove it and let the Japanese beetles eat somewhere else?

Are you practicing good garden sanitation, are you cleaning up those camellia leaves and blossoms after they fall, are you turning that compost pile and ensuring it heats properly in order to kill pathogens or pests?

If your growing zone allows it, perhaps you could plant your summer squash or tomatoes later and avoid that first rush of squash bugs or hornworms? (Keep in mind that hornworms are larval sphinx moths which are an important bat food source.)

Have you tried using row cover to exclude problem insects or other pests?

Be sure you’re not causing the problem. A little garden evaluation can do a world of good.

The decision you make here will determine the road you take in dealing with your pest issue. You’ve identified the pest, done some sleuthing and have an idea of the scope of the problem in your landscape. Now you have to decide what is the acceptable level of this pest to have in your yard.

And as always, “Right Plant, Right Place”.

#5 Determining Correct Control Measures

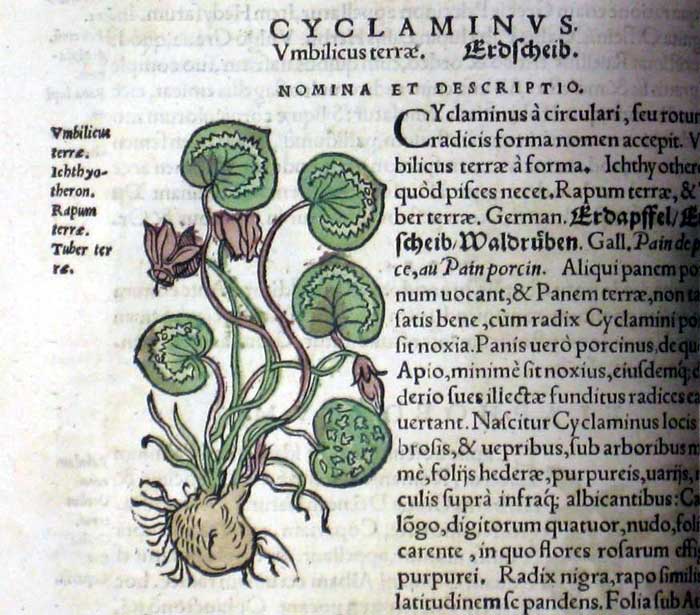

After analyzing the situation you’ve determined you need to engage in some form of pest control. But what should you use? Always strive to use the most benign yet specific form of control you can. Use the method which best targets the problem.

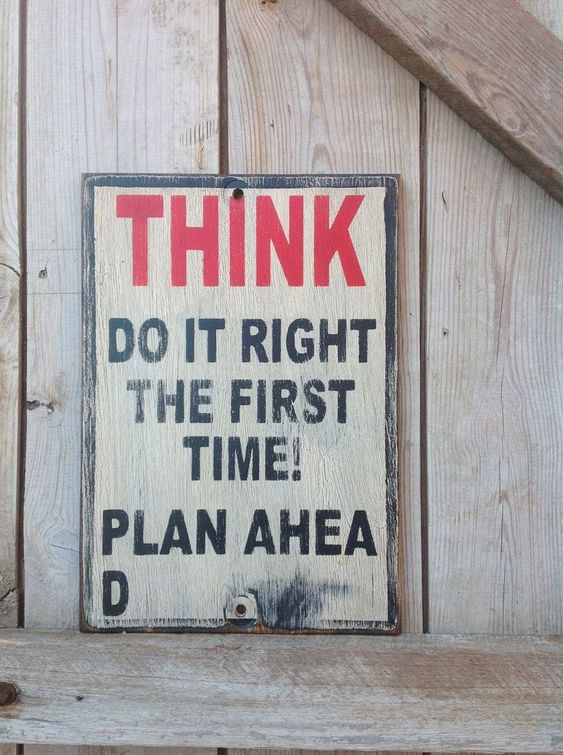

A combination of control methods usually give the best results. These include biological, cultural, mechanical/physical, and chemical/bio-rational measures. Start at the base of the pyramid (see above image) and work your way upward. Always allow sufficient time for methods to yield results. Pest problems rarely happen overnight. Early intervention is the key to control. See #2 above.

If you are forced to use pesticides always use them as a last resort, not as a first option.

Avoid using systemics on plants which are used by pollinators or other beneficial insects.

Avoid using broad spectrum pesticides and keep in mind that many pesticides which are approved for “organic” use are more toxic and less selective than “synthetics”.

An exception to the “avoid broad spectrum pesticides”: there can be times when a broad spectrum herbicide, such as glyphosate, is needed to kill both monocots and dicots. Use with care and follow label directions.

To review:

Please follow the IPM Five Step Process:

1. Always ID the pest correctly.

2. Get to know your own landscape. Monitor and assess pest numbers and damage to determine if intervention is truly needed. It often isn’t.

3. Use the pest’s life cycle and feeding habits to decide if or when management action is needed. Use their biology against them.

4. Prevent pest problems in the first place. Be sure you’re not part of the issue. “Right Plant, Right Place.”

5. If necessary, determine the correct control measures and always choose the most benign method which will do the job. Keep in mind products labeled “natural” may not be the best or safest option. Avoid DIY concoctions. They’re usually ineffective, harmful and an illegal use of ingredients.

Want to learn more about IPM?

http://www.npic.orst.edu/pest/ipm.html

https://ipminstitute.org/what-is-integrated-pest-management/

https://www.usda.gov/oce/pest/integrated-pest-management

https://www.epa.gov/safepestcontrol/integrated-pest-management-ipm-principles

Regional IPM centers

And last but not least:

* Link to my favorite cover of this great George Gershwin tune