As we head into Fall garden routines and leaves start to turn color, the smell and feel of the Fall weather is in the air. Winter is just around the corner and with those horticultural routines comes the urge to prune stuff . Both fruit producing and shade producing trees often get a hair cut during fall and winter months, herbaceous perennials are often cut back in the fall after bloom and before their winter rest so it seems a good time to blog about pruning before you get the urge! After years of pruning demonstrations for Master Gardeners and the public I have noted a common thread in how gardeners think about pruning. Pruning is a mysterious process. How we take that tangled mess of a plant (tree) and fix it? What do we prune? And the less frequently asked question: What do we not prune? To add confusion, some plants such as roses seem to have their own pruning “culture”. In this blog post I will cover the basic principles that apply to pruning all plants and then expand into specifics in upcoming blogs.

Plants don’t want to be pruned!

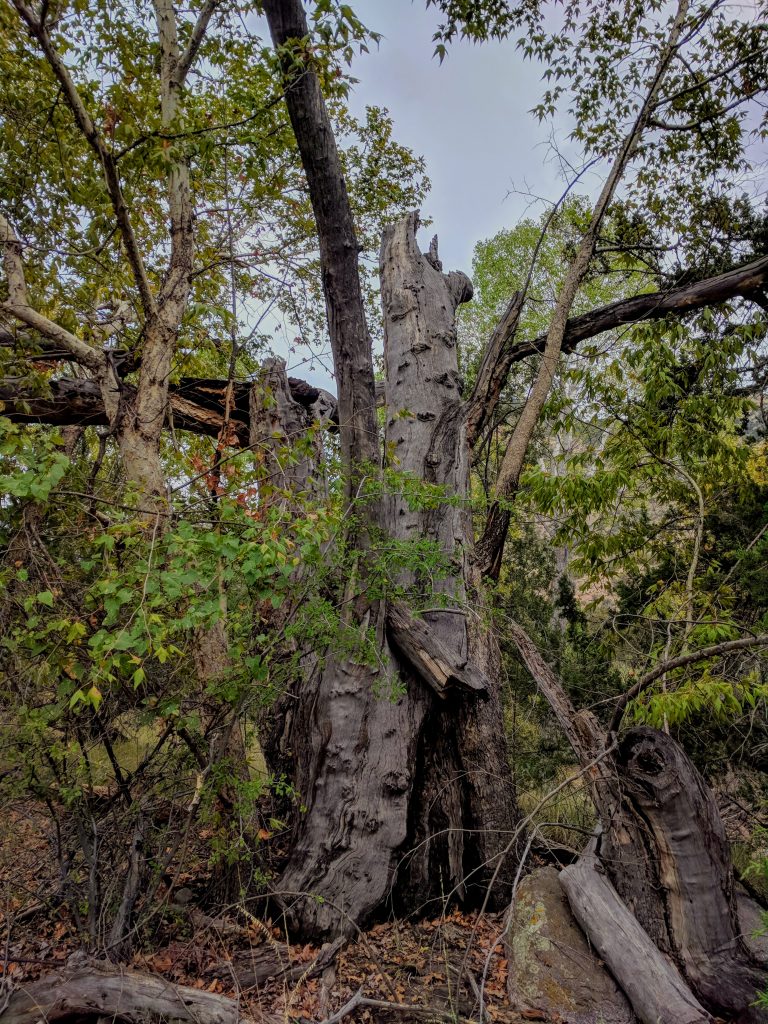

The first point is that no plant wants to be pruned. Gardeners prune plants because they think it is necessary for horticultural, aesthetic or safety purposes. Gardeners should temper their pruning by understanding plant responses that result from pruning. Generally plants don’t respond much when dead portions are pruned away. In some cases removing large dead portions of a plant will allow more light to enter and some response can occur, e.g., damage to portions of a plant not used to such sunlight intensity. So even a dead plant part may be doing something that you don’t understand. Also dead wood or dead plant parts may be part of some other organism’s home. Owls and other birds nest in cavities, some kinds of bumble bees will reproduce in old flower stalks of desert plants such as Nolina, etc. So dead plant parts are not always useless. If you are pretty sure that nobody else is using dead material go ahead and remove it if bothers your garden aesthetic.

There are two physiological responses to pruning

The two principles of pruning can be used to train plants and in the case of trees, produce a strong architecture that will not easily fail (drop branches). To achieve pruning goals two kinds of pruning cuts are used: the heading cut and the thinning cut. Heading cuts are often made in the middle of stems and do not have a branch that can take over the terminal role of the removed portion. Heading cuts are often used to reduce size or volume of plants. Thinning cuts remove branches at their origin. If thinning cuts are not too large and don’t allow excessive light into a canopy the plant will not respond by invigorating buds. Thinning cuts are used to maintain the natural form of a plant but can be overdone. Over-thinning results in plants that have so much light now entering that buds are invigorated and new shoot form in overwhelming and unnatural locations just as when heading cuts are made. Excessive use of thinning cuts can also produce trees that are “lion-tailed” where all the leaves occur at the end of Pom Pom branches. Remember from a tree or shrub point of view they don’t need or want to be pruned.

Back to plant responses. There are two responses that most plants have to pruning. When living portions are pruned the remaining portions are then invigorated. This implies that dormant or “latent” buds will grow that would not ordinarily grow so plants will produce flowers or foliage in new places. In this way we can re-direct the growth of plants to achieve pruning goals we may have. This is how we can pleach a tree to grow flat along a wall or produce topiary shapes with shrubs. These kinds of pruning that dramatically alter form of a plant will require successive and significant pruning to maintain the altered form or shape. Not all plants can tolerate this and even those that do can be subject to sunburn or other processes that cause them injury. The second common response to pruning is that the more a plant is pruned, the less it will grow—pruning is a growth reducing practice. Even though buds are invigorated through pruning they can’t make up for the lost leaves and buds taken away without utilizing stored energy. The overall effect of having leaves removed is to slow the growth of the entire plant. Pruning when used as high art results in Bonsai plants that are really stunted individuals with highly stylized forms.

Pruning devigorates plants

Since pruning removes leaves and buds (which make more leaves) it is a devigorating process. You are taking away a plant’s ability to harvest light energy and convert carbon dioxide and water to sugar. All this happens in leaves. The fewer leaves a plant has the less sugar it can accumulate and then the less work it can do in terms of growing. On old or slow growing plants pruning removes energy needed for growth and also the energy needed to make secondary metabolites or chemicals which fight insect and pathogen attacks. This is why old trees pruned hard often died not soon after or become susceptible to pathogens they may have been able to fight before the pruning happened. Whenever you prune something think about how you are taking away photosynthate and what it might mean to the plant.

Fruit Trees and Roses

We have to prune fruit trees to make them fruitful? NO. Fruit trees produce lots of fruit when they are not pruned. The goal of pruning fruit trees is to modify trees so fruit is:

• in an easy to pick location,

• so there is less of it

• and so the fruit that forms is of higher quality.

An unpruned tree will make the most fruit but it may not be the quality or size you desire or where you want it in terms of picking height.

The same goes for roses. There are many pruning schemes for roses, but the most flowers will be found on the least pruned shrubs. Flower size is mostly determined by genetics. Shrubs that are severely pruned will have fewer flowers than their unpruned counterparts.

Pruning and Disease

Pruning to remove diseased parts is often cited as a common garden practice. With some diseases like cankers and blights it is a good idea to prune out infected portions before they make spores or other inoculum to further infect the rest of the plant. In most cases it is important to prune well beyond the diseased portion so all of an infection is removed. Some diseases are “systemic” such as wilt diseases and while pruning will remove a dying portion it will not rid the plant of the infection. It is always best to identify the cause of disease even before pruning it from the plant. As we will learn in an upcoming blog I rarely recommend sterilizing your pruning equipment with disinfectants. A stiff brush and water is all that is needed when removing most diseased plant parts.

Pruning is a useful tool for gardeners. To get the most from the practice it should be conducted with knowledge of the effects it will have on the plant that is being pruned. This is quite variable and in some cases pruning is really contraindicated. While some plants like herbaceous perennials will be pruned to the ground either by the gardener or by frost, others maintain above ground architecture and pruning choices make permanent impact to many woody plants. In the next blog I will write about pruning young trees to create strong structure.

References:

Downer, J., Uchida, J.Y., Elliot, M., and D.R. Hodel. 2009. Lethal palm diseases common in the United States. HortTechnology: 19:710-716.

Downer, A.J., A.D. Howell, and J. Karlik. 2015. Effect of pruning on eight landscape rose cultivars grown outdoors Acta Horticulturae 1064:253-255

Chalker-Scott, L. and A. J. Downer. 2018. Garden myth busting for Extension Educators: Reviewing the Literature on Landscape Trees. J. of the NACAA 11(2). https://www.nacaa.com/journal/index.php?jid=885