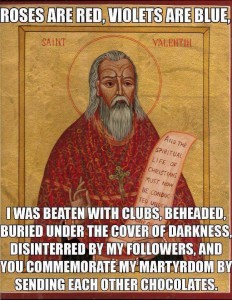

Ahhh….’Tis the time of year when we celebrate romantic love in homage to a 3rd Century priest who came up a head short for performing unsanctioned Christian weddings. (It is also of note that St. Valentine, or Valentinius as his friends called him, is the patron saint of bee keepers but, strangely, not of birds, flowers, or trees).

In celebration, many suitors, partners, spouses, fling-seekers, and woo-wishers will flock to florists, grocery floral counters, and even gas stations to purchase flowers, namely roses, that have likewise been beheaded.

Those roses, with all of their tightly wound petals, look nothing wild-type roses. Modern roses are the product of many centuries of breeding that started independently in China and the Mediterranean region.

So if the wild-type rose has a single row of five petals, how do breeders get all of those extra petals? They can just come from nowhere, you know.

The simple answer is that tissue that turns into stamens in the wild-type flower are converted to petal tissue. While early (and even contemporary) plant breeders may not understand the mechanism responsible for the doubling (gene expression), research is showing that the same gene is responsible for the doubling in both the Chinese and Mediterranean set of species/subspecies.

In a nutshell, what happens is that the different regions of the flower – sepals, petals, stamens, carpel – develop in response to the expression of a set of genes. It isn’t just the genes acting alone, though; it is their interaction in the tissues that makes the difference. These genes are grouped by the floral part they affect and are grouped as A-Function, B-Function, C-Function, and E-Function.

If you want to learn a whole lot more about it than I can ‘splain (it has been a few years since my last plant physiology class), this paper thoroughly explains the gene expression and evolution of the flower. Their figure depicting the flower model is informative, yet simple. I’ve included it (and its accompanying caption) below.

In the paper “Tinkering with the C-Function: A Molecular Frame for the Selection of Double Flowers in Cultivated Roses” researchers show that in lines from both regions of the world produced double flowers as a result in a reduction of expression of the C-Function gene AGAMOUS (RhAG) leads to double flowers. In Arabidopsis (every plant lab bench jockey’s favorite model plant), this reduction shifts expression of the A-Function genes toward the center of the plant, turning stamens into petals and carpels into sepals.

Now, one question I get from time to time is “why don’t these roses smell like the old-fashioned roses?” One answer is that as we breed for looks, we are breeding out genes responsible for scent oil production. So Shakespeare was actually wrong when he said that “a rose by any other name would smell as sweet.” That isn’t true these days.

So, I wish you a perfectly lovely Valentine’s Day, no matter how you celebrate. Just remember to whisper sweet nothings of floral gene expressions in your sweetheart’s ear. And remember to stop and smell the roses – if it is a variety that has a decent scent.

I love both.