In the last week, I’ve driven all the way from western Virginia, where the redbuds are blooming, to Tallahassee, FL, where red clover is everywhere. As I drove through the mountains north of Charlotte NC, I noticed some signs indicating that strong gap winds may blow down the valleys when atmospheric pressure patterns align to produce strong pressure gradients that drive the wind. I have discussed wind before in previous posts (“Who has seen the wind?” and “Does wind chill affect plants?”) so you can find the basics of what causes wind and some of the different kinds of local winds by going to those posts. In today’s article I want to share some different local names for winds and other local weather and invite you to share your own local weather names. Note that this is not a complete list, but I will provide links at the end that prove a bigger sample of all the names that are used around the world to denote different kinds of weather, especially wind.

Local weather names based on topography

Local mountains and valleys can cause a big variety in the types of winds we observe. Generally, these winds can be classified as katabatic winds blowing downhill and anabatic winds blowing uphill. The direction depends on the time of day due to heating but also to large-scale weather patterns that direct the flow of air. Local winds can also occur due to changes in the heights of the ridges so that where the ridges are low, air can spill over the mountains in the gaps between peaks. Winds blowing downslope can also accelerate as they move to lower elevations, increasing their strength. Those winds can be very strong because of the funneling effect of the terrain leading to warnings like the ones I saw on Interstate 77 in the northern North Carolina Mountains. Some of these local winds in other parts of the world are called the Viento Zonda (or Zonda wind) in Argentina, the Williwaw in the Alaskan Panhandle, Karaburan in Central Asia, Chinook wind along the Front Range of the Rocky Mountains in the USA, Mistral in France, and the Warm Braw in the Schouten Islands north of New Guinea. You can read more about each of these by looking online at Wikipedia or other sites (link below). Winds which are affected by topography can provide good sources of steady wind for wind farms.

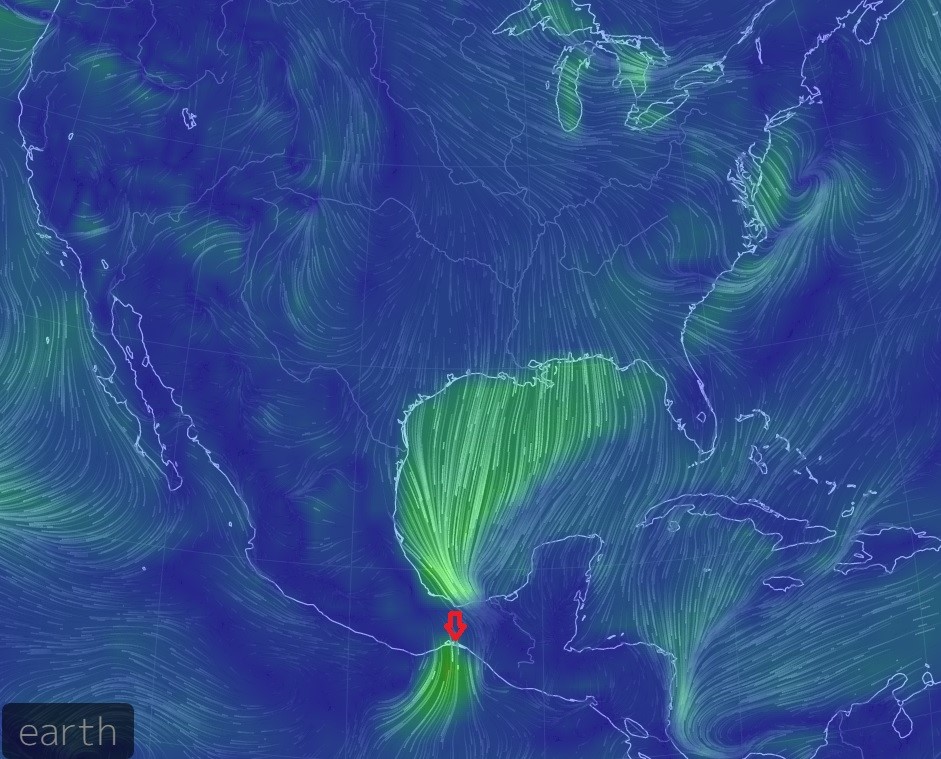

One of the most interesting large-scale topography-driven winds is the Tehuantepecer in southern Mexico which begins in the Gulf of Mexico (after coming south across North America) as a north wind that crosses the Mexican isthmus and blows through the gap between the Mexican and Guatamalan Mountains. It is so strong that it can be felt as much as 100 miles out to sea. This happens several times a year, especially in winter when the wind is more often from the north, and is amazing to see on https://earth.nullschool.net/ when it happens. In fact, as I am writing this on Thursday (March 28, 2024) it is happening today! How cool is that?

Local weather names based on changes of air mass

Some winds are named for abrupt shifts in atmospheric temperature and humidity when air from a different source region moves in. They can be small-scale changes due to outflows from individual thunderstorms like gust fronts or can be larger-scale changes due to wind blowing an air mass with colder, hotter, or drier characteristics into the area.

Some of the winds associated with drier and dustier conditions occur near desert locations as the wind shifts to bring in air from the desert regions to replace the air that was already there. One of the most common terms for one of these is haboob, which originated in Sudan but is now used in the western U. S. (Haboob basically means “dust storm” in Arabic but sounds a lot more exotic). A haboob is associated with a wall of hot, dusty air that moves into the region from the desert, bringing low visibilities to the region (often resulting in car accidents as drivers caught unawares can be blinded by the sudden change in conditions). Other dry winds include the Khamsin in Egypt and the Red Sea region, the Scirocco in North Africa and the Mediterranean, and the Harmattan in West Africa.

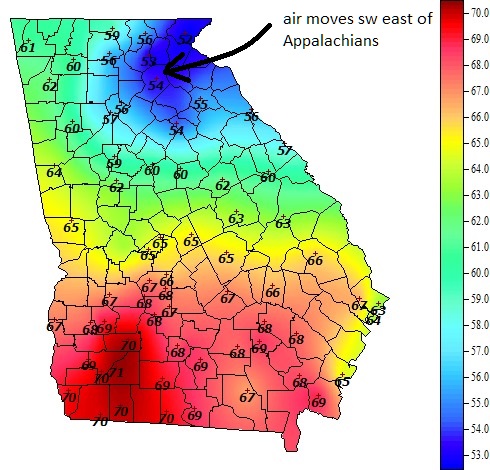

Cold winds include the Blue Norther, a fast-moving cold front that moves in from the north that can send temperature plummeting by 20-30 degrees in a few minutes, the Bora in the Adriatic region, the Khazri in the north Caspian Sea, the Montreal Express in New England, and the Norte in Mexico. In the Southeast US, we have what we call the Wedge, which is a shallow layer of cold air that moves south along the eastern slope of the Appalachian Mountains under northeast flow, bringing clouds, cold weather, and the chance of ice storms to the region in spring. The Wedge is partly due to topography as well, since the cold air is so shallow that it can’t move west over the Appalachian Mountains and thus is forced down to us in parts of the Carolinas and Georgia. Hot dry winds include the Brickfielder in southern Australia, the Leveche in southern Spain, and the Diablo and Santa Ana winds in California, which are also affected by air moving down from the mountains into coastal areas of the state when high pressure dominates the Southwest.

Local winds are associated with thunderstorms

In addition to the wind names associated with topography and change of air quality there are also some names that are tied to smaller weather events like hurricanes and thunderstorms. Those include the Kalbaishakhi in India and Bangladesh, the Bayamo on Cuba’s southern coast, the Pampero in Argentina and Uruguay, the Cordonazo on the west coast of Mexico, and the Borasco in the Mediterranean. Strong winds associated with thunderstorms can cause tremendous damage to gardens, trees, and buildings and can cause problems with flights and road transportation. Since it is spring and we are entering severe weather season for a lot of the US, it’s a good reminder that it does not need to be a tornado to cause significant damage—straight-line winds can be just as severe.

Knowing your local climate is important for gardeners

Anyone who lives for a long time at a location will start to recognize the local weather and climate patterns that govern your local garden conditions. If you are really dedicated, you can even measure these variations. If you know that in certain seasons, you are more likely to experience very dry dusty air, you might consider plants that can survive those conditions with less care. If you live in an area that is subject to frequent strong local winds, you will need to plan your garden to place more wind-resistant plants where the air flow is the strongest or else construct a wind shelter to keep more sensitive plants safe. Buildings can also affect the wind flow and can cause “wind tunnels” where the air is constricted and blows faster in the narrow passage.

Note: For those of you who wonder about the title of this post, Maria (sometimes listed as Mariah) is a fictional wind popularized in “Paint Your Wagon” (Lerner and Lowe, 1951) and by the Kingston Trio (1959). The name may have originated with the 1941 book “Storm” by George R. Stewart according to my colleague Jan Null of Golden Gate Weather Services.

Sources of more local wind information

Here are some websites that have listings of additional local winds, although none of them is a complete list, I am sure.

Wikimedia (with links to most of the individual winds): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_local_winds.

GG Weather: https://ggweather.com/winds.html

U. K. Met Office: https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/weather/learn-about/weather/types-of-weather/wind/wind-names

If you have a local name for the wind or weather in your region, please share it in the comments!