You may have read in the news earlier in May that NOAA has updated their “normals” for temperature and precipitation at stations around the country. In climatology, normals are the calculated averages over a specified time period. Usually, we use a 30-year period to capture what the average weather is like in a time period that is about the length of a generation, but now NOAA is also calculating normals based on other time periods like 15 years. Utility companies often use 10-year normals because electricity-generating technology and energy demand is changing so quickly that 30 years is considered too long.

Why do they update the normals every 10 years?

Normals are updated every ten years, so the new period of 1991-2020 is replacing the older normal period of 1981-2010. They only do it every ten years because a lot of work goes into quality control of the data as well as adjusting for station moves, missing data, and changes in observation time. All of those events can introduce artificial “climate change” into the record, leading to averages that don’t really represent the current climate at the location of the station being described. Climatologists follow rigorous methods of making these corrections, and even scientists who are skeptical about their techniques by and large end up with nearly the same corrections if they follow scientifically and statistically accurate methods. NOAA has provided some FAQs that explain more about the process of creating the new normals if you are interested.

How are the normals changing?

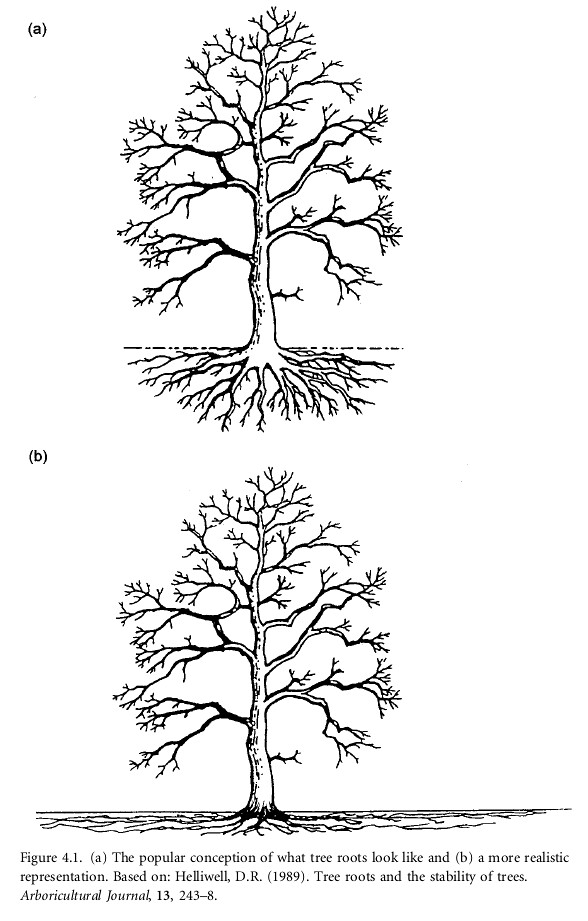

Determining what a “normal” temperature is when the temperatures are relatively stable is easy, because you can use any long-term average to describe the expected temperature. But when the climate is not stable but is changing over time, what you think of as “normal” weather changes as cooler decades get replaced by warmer decades. For example, here is a graph of the annual average temperature for the Midwest with 30-year normals plotted on it for 1961-1990 (green), 1971-2000 (blue), 1981-2010 (violet), and 1991-2020 (yellow). Early in the record, the 30-year averages (not shown for the early time periods) did not change all that much from one decade to the next because there was no trend towards warmer conditions. But now, every new set of normals gets warmer. We are not living in the climate that our parents or grandparents grew up in! This Washington Post article by Bob Henson and Jason Samenow provide an excellent overview of all the changes that we are seeing and why those changes are occurring. We can expect the next set of normals to be even higher as the temperature continues to rise.

How are the normals changing across the country?

The annual average temperature is not changing by the same amount everywhere. The map below shows that even though most of the lower 48 states are getting warmer, the upper Great Plains got cooler when the latest normals were calculated. Western Texas and parts of New Mexico had the largest increases in temperature. NOAA also has these maps for select months.

Of course, it is not just the annual average temperature that is changing. The minimum temperatures are increasing at almost twice the rate that the maximum temperatures are rising. Most but not all monthly temperatures are rising at many stations. The precipitation is changing in northern and western high-elevation areas from snow to more rain. Most parts of the US are getting wetter, but the Southwest is getting drier. And the rain is coming in higher intensity bursts, with longer dry spells between precipitation events in many areas.

As temperature and precipitation change, other variables that are related to heat and moisture are also changing. The length of the growing season is increasing in most of the country, allowing gardeners to plant new varieties of heat-loving plants but stressing plants that prefer colder temperatures. This is a concern for peach farmers in Georgia, for example, since peach trees need a certain number of hours below 45 F to set a good crop of fruit. As the temperature rises, it becomes harder for the trees to get the cold weather they need to produce enough blooms. Other plants like lilac, which I enjoyed every spring when I was growing up in Michigan, do not grow in Georgia because of the heat and may someday be scarce even in the Midwest. Growing degree days (a measure of the amount of time above a base temperature, commonly 50 F, used to track plant development) are increasing, affecting the growth patterns of commercial crops as well as garden plants. Humidity is also rising, leading to more fungal diseases and more oppressive working conditions for gardeners and farm workers who are affected by both the higher moisture levels and more frequent extremely hot days. At the same time, higher evapotranspiration from plants accelerates the water cycle, making droughts (and floods) more likely.

Where do you find your local normal weather?

If you are interested in finding your new “normal” temperature and precipitation and comparing it to the old values at your location, you can find instructions at my daily blog. Of course, there are many other places to find it as well—just do a search online and several sites should pop up. If you want to do an average over a different set of years, you can use the Custom Climatology Tool from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln to do those calculations.

Ultimately, the changes in the climate reflected in the new normals will show up in other garden-related values such as the USDA Plant Hardiness Zone, although it’s hard to know exactly when those values will be updated. Even without knowing exactly what zone you are likely to be in over the next decade, with the continuation of rising temperatures that we expect, you can try out plants that are just on the warm side of your current zone to see how they do. Of course, your local microclimate will also affect their ability to thrive, so don’t forget to consider that too.

Should we just get rid of “normals” since they keep changing? I don’t think so, since they do provide useful information about what we expect over a number of years. You can use normals to determine what clothes to have in your closets, how much heating and cooling you need for your homes, and what to plant in your garden. Just be aware– “normal” is no longer normal in a changing climate.