The Garden Professors have previously written about the ubiquitous garden center product, SUPERthrive, here and here. The manufacturer claims a plethora of beneficial uses for SUPERthrive —everything from Christmas tree care to turf to hydroponics. They claim SUPERthrive will “revive stressed plants and produce abundant yields” and that it “encourages the natural building blocks that plants make for themselves when under the best conditions” thus “fortifying growth from the inside out,” but I know of no body of rigorous, peer-reviewed literature to support any of those claims (1, 2, 3, 4). In fact, I’m not entirely sure what those claims really mean, but I’m encouraged on their website and bottle to use it on every plant, every time I water, to receive these amazing benefits!

A test case

The hydroponics claim intrigued me because during the winter months I grow plants hydroponically under lights. One of the benefits the manufacturer claims is “restores plant vigor” and “works with all hydroponics systems.” As a plant scientist, and knowing something about the ingredients, I was skeptical to say the least, but I thought that if SUPERthrive was going to show any beneficial effect it would surely be in hydroponics since that is a more uniform environment than outdoors. So, I shelled out my $11 for 2 oz (the things we do for science!) and set off to design a simple experiment.

The hypothesis

A typical experiment like this starts with what we call the null hypothesis (denoted “H0”). The null hypothesis is defined prior to the experiment and often states that we think there will be no difference between the treatment and control. In this case, my null hypothesis is that the SUPERthrive treatment will have no effect on the mean fresh weight of the harvested lettuce relative to the control lettuce. Note that I haven’t made any hypotheses about other parameters that might be important, e.g., flavor, compactness, number of leaves, color, disease incidence, survival rate, etc. For this experiment I am interested in only one thing: total harvested weight as a signifier of healthier plants.

After the data is collected and analyzed, we decide whether to accept or reject the H0 by running an appropriate statistical test. If there is no statistically significant difference, then we cannot reject the H0—that is, we accept the H0 that there is no difference between treatment and control. If there is a statistically significant difference between treatment and control, then we say we reject the H0 and conclude that the treatment did have an effect. Keep in mind, sometimes no difference between treatment and control is a good thing, e.g., in toxicity studies.

Experimental design

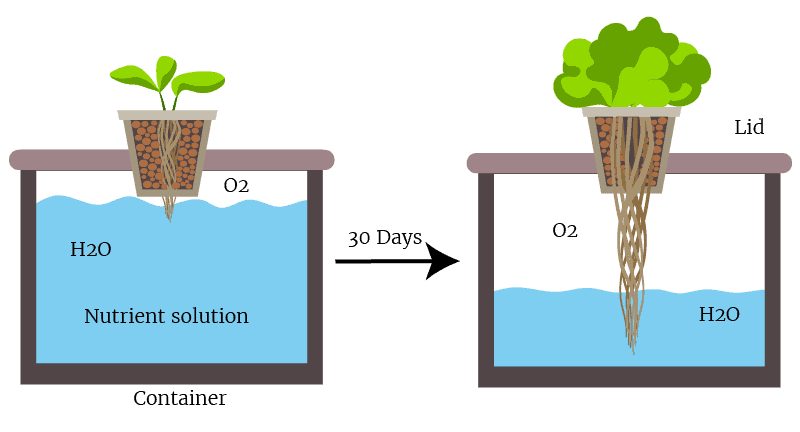

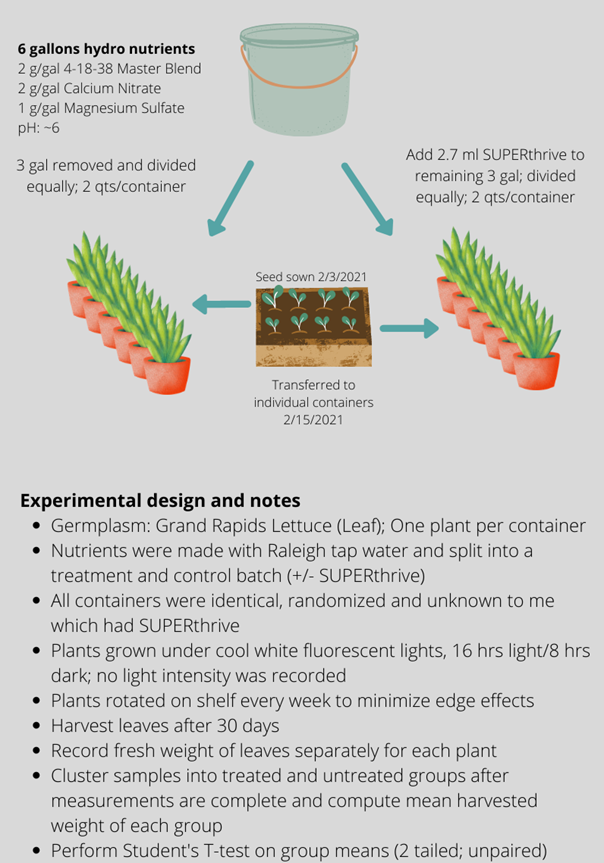

With my skeptical spectacles on, I set up my experiment to test my hypothesis. I made a six-gallon batch of hydroponics nutrients suitable for leafy greens. I split the batch in half and added SUPERthrive, per the manufacturer’s dilution recommendation, to one of the three-gallon aliquots as the treatment. I then divided the control and SUPERthrive treatment each into six individual, identical, two-quart containers. I thus had six independent replicates of a treatment and a control. (See Figure 1 below for a schematic of the experimental design.)

To further avoid any experimenter bias, I had my wife assign numbers randomly to each container, record which were SUPERthrive treatment and which were untreated control, and then re-sort all the containers. I had no idea which containers contained which nutrient mix. I did not open the “secret decoder envelope” until after all measurements were complete!

Into each of the 12 containers I placed a 12-day-old lettuce seedling, taking care to select plants that were of equal size and leaf number. The containers were then placed under my lights (cool white T8 fluorescent) for the remainder of the experiment. I rotated the rows of plants several times to try to control for any edge effects in my grow area. After 30 days in the containers, I harvested and weighed each plant.

What did my experiment show?

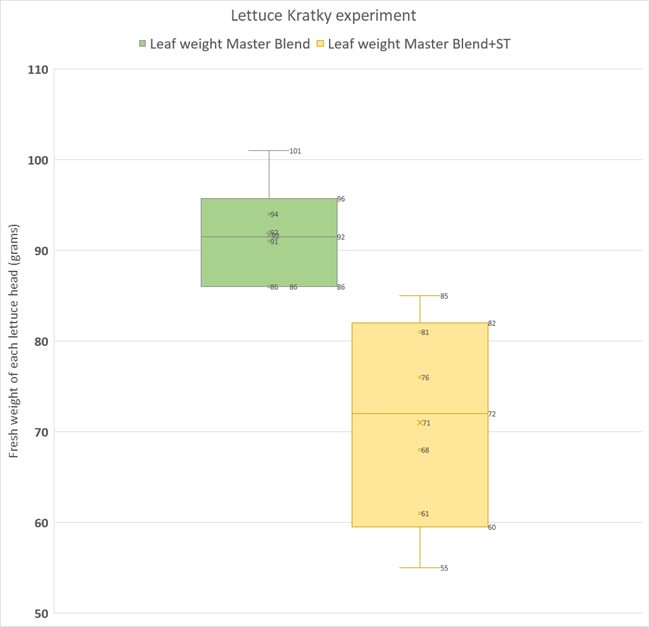

The graph below is a box and whisker plot that shows the spread of the data and the mean for each group in grams of harvested fresh weight of the plants (roots were removed). In my experiment, the SUPERthrive treatment showed a clear drop in harvested fresh weight! In fact, the heaviest SUPERthrive plant weighed less than the smallest control plant, and the SUPERthrive set was much more variable in harvested weight. These results surprised me a bit.

A standard statistical test (Student’s T-test, unpaired, two-tailed) was performed to show that that there was in fact a statistically significant difference (p<<0.01) between the two groups. Thus, we can reject the H0 (remember our null hypothesis is that there will be no treatment effect) and conclude that there is a difference between treatment and control harvested weights, with the treatment mean plant weight being significantly smaller than the control mean plant weight.

What can we make of this experiment?

Well, we need to keep in mind a few things.

1) Six replicates is a very small sample size; this could be a spurious, unlucky result. There is always some distribution of growth rate, even in a uniform genotype. Did I get unlucky and happen to put six plants that would always be on the smaller end of that distribution into SUPERthrive?

2) After analyzing the data, I discovered that four of the SUPERthrive plants ended up in the same row and were the smallest heads in the experiment (sometimes you flip a coin and get four heads in a row!). Could this be the reason for the unexpected results? The other two treated plants were in the other two rows, but neither was as large as the smallest control plant.

3) I do not have a perfectly controlled environment like one would find in a lab or even in a larger growing facility. However, something marketed with such aggressive claims of amazing plant health benefits and vigor should give a noticeable effect under a variety of imperfect, real-world conditions, such as those one would find in a home garden situation, don’t you think?

4) Perhaps my plants were already growing at their maximum potential and there was nothing for SUPERthrive to “improve.” Afterall, hydroponics indoors is already a relatively stress-free environment, as the SUPERthrive manufacturer also points out. Then what do they think their product is improving in hydroponics? Would I have seen an effect under less-than-ideal or more stressful conditions then? This could certainly form the basis of other testable hypotheses.

Conclusions

What I think we can conclude is that in this experiment, with this genotype of lettuce, and under these hydroponics conditions and environment, SUPERthrive had no positive effect whatsoever and may have even had a negative effect. Under other conditions would one see a positive effect? Possibly. Would different plants or genotypes respond to the SUPERthrive differently? Possibly. We must always be careful of over-extrapolating both positive and negative results from a single experiment.

But, because the individual ingredients have not been shown to provide any beneficial effect, and no plausible mode of action is given by the manufacturer for their broad general claims, we should remain highly skeptical. As pointed out in the previous post, the SUPERthrive manufacturer has certainly had plenty of time to scientifically demonstrate efficacy of their product, since they proclaim to be “always ahead in science.”

Because the results showed a clear and unexpected negative effect, the experiment surely needs to be repeated. Repetition is a central tenet of science. I hope to share additional results with you in a post later this spring—after all, I have a whole bottle of SUPERthrive and we love salad!

References

- Banks, Jon & Percival, Glynn. (2012) Evaluation of Biostimulants to Control Guignardia Leaf Blotch (Guignardia aesculi) of Horsechestnut and Black Spot (Diplocarpon rosae) of Roses. Arboriculture & Urban Forestry. 38(6): 258–261

- Banks, Jon & Percival, Glynn. (2014) Failure of Foliar-Applied Biostimulants to Enhance Drought and Salt Tolerance in Urban Trees. Arboriculture & Urban Forestry 40(2): 78–83

- Chalker-Scott, Linda. (2019) The Efficacy and Environmental Consequences of Kelp-Based Garden Products.

- Yakhin Oleg I., Lubyanov Aleksandr A., Yakhin Ildus A., Brown Patrick H. (2017) Biostimulants in Plant Science: A Global Perspective. Front. Plant Sci., 7:249