One of the things I miss (and sometimes don’t miss) after my move from West Virginia to Nebraska is writing my weekly garden column for the Charleston Gazette-Mail newspaper. It was a great way to always keep thinking about new things to talk about and a great way to connect with the public.

After I left, the newspaper replaced me with a team of 4-5 local gardeners who would take turns writing about their different gardening insights and experiences. Some have been really good, like the ones who were my former Master Gardener volunteers. However, sometimes I find the bad information and attitude of one of the writers off-putting and even angering.

Take for example this missive which equates sustainable agriculture (a term which is pretty well defined as a balance of environmental stewardship, profit, and quality of life) solely to permaculture and biodiversity while espousing an elitist attitude about “no pesticides, no fossil fuels, no factory farms, growing all you need locally and enhancing the land’s fertility while you’re at it.” He got all this from an old photo of dirt poor farmers who were apparently practicing “permaculture” – which I’m sure was foremost on their minds while they were trying not to starve to death. The fact is that our food system (and the food that today’s low income families) depends on comes from a mix of small and large farms. And most of those “factory farms” are actually family owned, and not everyone can afford to grow their own food or pay the premium for organic food (which still has been treated with pesticides and is in no way better or healthier than those conventionally grown).

Now, I know I no longer have a dog in that fight, but when I see bad information, especially when it is aimed toward an audience that I care deeply about I just have to correct it. So two weeks ago when I saw his latest gem of an article berating a woman (and basically anyone) for using lumber (and those who work as big box store shills to promote them) to build raised bed gardens and should instead till up large portions of their yard for the garden I was aghast. Putting aside the horrible advice to till up the garden (which we’ll talk about in a minute) or the outdated recommendation of double digging (proven to have no benefit), that advice is just full of elitist assumptions toward both the gardener and toward the technique. It is especially ridiculous and ill-informed to suggest that tilling up a garden and destroying the soil structure is much better ecologically speaking that using a raised bed (and we’ll talk about why in a little bit).

Don’t want to do a raised bed? Fine, it isn’t for everyone. But that doesn’t mean you should go out and till up a large patch of land that will degrade the soil, lead to erosion and runoff, and reduce production. It does not do anything to improve drainage nor aeration.

So let’s do a breakdown of why I find this article, its assumptions, and bad science so distasteful:

Bad Assumptions (and you know what they say about assuming)

The gardener didn’t have a reason for a raised bed other than she had been told that’s the way you do it.

This assumption fails to take into account the many different reasons why a gardener may prefer to use a raised bed. Does she or a family member have mobility limitations where a raised bed would provide access to be able to garden? Or does she have space limitations for a large garden patch? Would a raised bed make it easier for her to manage and maintain the garden? Making a blanket pronouncement against the technique fails to use empathy to see if it actually would make gardening more accessible or successful for the gardener. Is she wanting a raised bed because the soil in the ground at her house is too poor or contaminated? West Virginia is notorious for having heavy clay, rocky soil that is pretty poor for growing most crops. It can take years of amending to get it even halfway acceptable for gardening. Or perhaps she lives on a lot that had some sort of soil contamination in the past and she’s using raised beds to avoid contact with the contaminated soil.

Raised beds also have some production advantages – the soil heats up faster in the spring, allowing for earlier planting. A well-built soil also allows for improved drainage in areas with heavy soil or excess moisture.

The gardener has access to equipment to till up a garden space, have the physical strength and endurance to hand dig it, or is she able to afford to pay someone to do it for her?

Raised beds can often be easier for gardeners to build and maintain, often not needing special equipment or heavy labor. If the gardener isn’t supposed to benefit from these efficiencies, how will she go about tilling up the soil for her new garden. Does she or a friend/neighbor have a rototiller or tractor she can use? Is she physically capable of the often back-breaking work of turning the soil by hand? Or does she have money to pay someone to do it for her? So these “cheaper and easier” methods he describes could actually end up costing more and being harder than building a raised bed.

The raised bed has to be built out of lumber, which apparently only comes from the Pacific Northwest and is a horrible thing to buy. First off, raised beds can be built out of a number of materials. The list usually starts with lumber. Some people tell you to use cedar (which does primarily come from the PNW), since it is more resistant to decay, but plain pine that’s treated with a protective oil or even pressure treated is fine (it used to be not OK back before the turn of the century when it was treated with arsenic, but most experts now say it is OK since it is treated with copper). The dig against the PNW lumber industry is as confusing as it is insulting, since there’s lots of lumber produced on the east coast, and even a thriving timber industry right in West Virginia. Most lumber these days is harvested from tree farms specifically planted for the purpose or by selective timbering that helps manage forest land for tree health and sustainability.

The list can go on to include landscaping stone, concrete blocks, found materials like tree branches, and on and on. These days, you can even buy simple kits you can put together without tools and with minimal effort that are made of high-grade plastic or composite lumber. They’re getting cheaper every year, and can be especially affordable if you find a good sale or coupon.

Heck, a raised bed doesn’t even require the use of a frame at all….just a mound of well amended soil in a bed shape will do. No need to disturb the soil underneath, just get some good topsoil/garden soil in bulk or bags from your favorite garden center, mix it with a little good compost, and layer at least 6 inches on top of the soil. Use a heavy mulch on top if you are afraid of weeds coming up through the new soil.

The soil she’d buy is trucked in from Canada.

I’m guessing this has some sort of assumption that the soil a gardener should be putting a raised bed is like a potting mix composed primarily of peat moss. While many gardeners are trying to decrease the use of peat moss, which is a non-renewable resource harvested from Canadian peat bogs, the recommended soil for a raised bed is not potting mix or one that even contains a large amount of organic material. The recommended composition of raised bed soil is largely good quality top soil, which is usually sourced locally, mixed with a bit of compost which could be from home compost, a local municipal composting facility or producer, or from a bagged commercial product that is likely from a company that diverts municipal, agricultural, and food wastes into their product.

Bad Advice based on Bad Science (or lack thereof)

Tilling or disturbing the soil is a common and acceptable way to prepare a garden.

More and more evidence is emerging that tilling or disturbing the soil is actually one of the worst things you can do in terms of both production and environmental impact in agricultural production. First, tilling disturbs and in some cases destroys the soil structure. Destroying the soil structure allows for increased erosion, especially when the bare soil is washed away during heavy rains or blown away in heavy winds. Excess tillage and wind is what actually led to the dust bowl, which actually led to the early promotion of conservation tillage practices through government programs like Conservation Districts (and also gave us some great literature, thanks to John Steinbeck). Aside from the soil particles that erode, having open, tilled soil leads to nutrient runoff that contribute to water pollution.

One other structure negative is the production of a hardpan or compressed layer of soil that occurs just below the tilled area. This results from the tines of a tiller or cultivator pressing down on the soil at the bottom of where it tills and can drastically reduce the permeation of water and gasses through the soil.

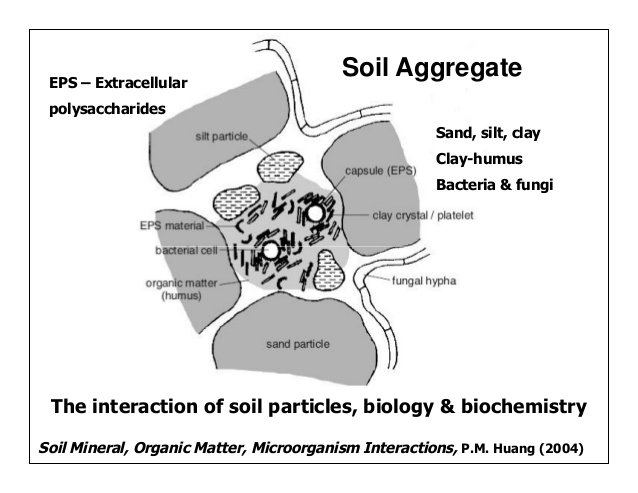

The aggregates in the structure of un-disturbed soil provide myriad benefits to soil health, especially in providing the capacity for the growth of good microorganisms. Studies have shown that the population of soil microbes is drastically higher in agricultural soils that haven’t been tilled. Therefore, tillage reduces soil biodiversity.

One of the reasons for increased soils microbes in no-till soil is an increase in soil organic matter. No-till allows for some crop (roots, etc) to remain in the ground and break down. Tillage also incorporates more air into the soil, which does the same thing that turning a compost pile does – it allows the decomposition microbes to work faster in breaking down organic matter. This increased activity then decreases the amount of organic matter. So tilling the soil actually reduces organic matter. The structure and organic matter also allows no-till soil to have a higher Cation Exchange Capacity, or ability to hold nutrients.

When the carbon in the organic matter in the soil is rapidly depleted after tillage, it doesn’t just disappear. The product of the respiration from all those bacteria and fungi is the same as it is for all living creatures – carbon dioxide. The organic matter held in the soil therefore provides a great service (we call this an ecosystem service) in that it sequesters carbon from the environment. This can help mitigate climate change and even effect global food security.

Double digging does a garden good.

Look through many-a garden book and it will tell you to start a garden bed by double digging, which is a term used to describe a back breaking procedure where you remove the top layer of soil, then disturb a layer beneath it and mix up the layers. While it may not be as drastic as running a tiller or tractor through the soil, it still destroys the structure with the same negative outcomes as above. Additionally, while many gardeners swear by it, there is evidence that the only benefit to come from it is to prove to yourself and others that you can do hard work. It has no benefit for the garden and usually negative effects on the soul, psyche, and back of the gardener.

Large tilled up gardens are easier to maintain. One of the benefits of gardening in a bed, raised or otherwise, is that the close spacing allows you to grow more stuff in a smaller area. By reducing the area under production, you also reduce the labor and the inputs (compost, fertilizer, etc) that are used. Using the old in-ground tilled up garden method where you grow in rows means that you have more open space to maintain and will be using inputs on a larger area that really won’t result in more production (it is really wasted space and inputs).

So, how do you start a garden if you don’t want to build a raised bed and know that you shouldn’t disturb the soil?

So you realize that tilling up the soil is really bad from both an ecological and production standpoint, but you don’t want to build a raised bed structure? That’s perfectly fine. Gardening in a bed, raised or not, is a great, low-impact gardening practice.

To get started, you don’t have to disturb the soil at all. Simply adding a thick layer of compost and topsoil on top of the soil in the general dimensions of the bed is a good way to start a bed. No need to till or disturb. And over time, the organic matter will eventually work its way down into the soil. If you have really heavy (clay) soil, you’ll probably want to start with a fairly deep (at least 6 to 8 inches) layer of soil/compost.

Just cover with your favorite mulch to keep it in place and reduce weeds (I prefer straw and shredded newspaper, but you can use woodchips as long as you don’t let them mix in with the soil – something I never can do in a vegetable garden where I’m planting and removing things on a regular basis). Keep in mind that a good width for a vegetable bed is about four feet and you want a walkway of at least two feet between them. This allows you to not walk on the good soil, which can cause compaction.

If the spot where you want to put your bed is weedy, use your favorite method to remove weeds before laying down the layer of compost/soil. This could be through herbicide usage (keeping in mind most have a waiting period to plant, though some are very short) or mulch. If you are planning ahead (say at least a year), our Garden Professors head horticulturalist suggests a layer of woodchip mulch 8-12 inches deep that can turn a lawn patch into a garden patch. They reduce the weeds and build the soil as the break down.

Good article- thanks. But one question -towards the end, you say: “tust cover with your favorite mulch to keep it in place and reduce weeds (I prefer straw and shredded newspaper, but you can use woodchips as long as you don’t let them mix in with the soil ” – why not?

thanks,

Laurie

Laurie – mixing in woodchips or any other carbon heavy material in the soil will tie up nitrogen in the system as the microbes in the soil try to decompose it.

Can you cite research that confirms this statement?

Here’s a review our own Linda CS did on mulches. In a nutshell: N deficiency occurs at the mulch:soil interface. If the mulch is mixed in, then that makes the interface within the soil. She also goes on to point out that woodchip mulch on veggie beds could be an issue because many vegetables are shallow rooted.

Linda’s Review

“A zone of nitrogen deficiency

exists at the mulch/soil interface (Chalker-Scott, unpublished

data), possibly inhibiting weed seed germination while having

no influence upon established plant roots below the soil

surface. For this reason, it is inadvisable to use high C:N

mulches in annual beds or vegetable gardens where the plants

of interest do not have deep root systems.”

You want someone to prove to you that immobilization exists and that the C:N ratio matters? This is basic soil science. Here’s a very elementary primer: https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/nrcseprd331820.pdf

Sorry but you are just wrong. Wood chips on top of soil does NOT decrease nitrogen in the soil. There are multiple published articles on this topic. Wood chips tilled INTO the soil will of course decrease nitrogen.

Whew! That’s a meaty post. I agree with much of it, but here’s a couple of quibbles.

First, I’m not sure why “soil from Canada” would be derogatory. We’re actually not bad people, on the whole. In the specific case of peat moss, I think harvested areas can be regenerated, making it a sustainable resource, and in any event the amount of land that is being or has been harvestedis a miniscule proportion of the total area covered by peat bog in Canada.

Second, isn’t copper deadly poisonous to invertebrates? That’s why it’s been banned as an anti-fouling agent on boats. Cedar (or “Western Redcedar,” which of course isn’t cedar at all) seems to me to be a better choice. It would be cheaper in the US if someone hadn’t imposed tariffs on “softwood from Canada.”

I’ll let John respond to this comment as well, but the issue about peat moss is serious and a topic that I’ve written about previously. Peat bogs require centuries to develop – like old growth forests. Sure, can can eventually regrow, but they aren’t really a “sustainable resource.” And the amount of greenhouse gases generated from destroyed peat bogs significantly contributes to both climate change and ozone layer depletion.

What Linda said! Plus…

As for copper, the source linked to states that there is very little potential for the copper to leach from the lumber and that it bonds pretty tightly to the soil. So there would be very little that is released (not enough to harm invertebrates) from the lumber and it wouldn’t move too far from the lumber.

The opinion of the author regarding organic food production is categorically untrue. Every organic farmer I have ever met has never used chemicals – neither chemical-based fertilizers or pesticides. Making such flagrant statements negates the care and stewardship small organic farmers provide in delivering wholesome produce to market

Many organic farmers also keep bees. If you maintain hives, you cannot use chemical pesticides as these systemics kill bees and other pollinators. It is also not “elitist” to support the soil’s microbial community – essential to providing nutrients to the plant – the nutrients the plant actually needs rather than the force-feeding that chemical fertilizer instigates. Pesticides, in particular, destroy the microbial community. Organic growing – stewarding the earth – supports and stewards the soil – not an “elitist” practice.

Last, author might check out the Cornucopia Institute’s vast resources on research comparing nutrient value between traditionally grown produce and organically / biodynamically grown produce. While there, author might also check out the number of family farmers that are part of the Institute’s network and the commitment these farmers and consumers have to non-chemical based food production. https://www.cornucopia.org

I’ll let John respond to this too, but some of your comments are factually incorrect.

1) Organic farmers DO use chemicals. There are huge lists of fertilizers and pesticides approved for organic use by the USDA and listed by OMRI. Some of them, like neem and other broad spectrum insecticides, kill bees. They are chemicals. Period.

2) Biodynamics is entirely unsupported by science. I’ve personally reviewed the literature on biodynamic preparations and published a peer-reviewed article on the topic.

Linda is correct. Organic production can include the use of approved organic pesticides. The use of such pesticides does not negate the producers environmental stewardship – any pesticide can be used responsibly, by the label, and still fall within stustainable agriculture and stewardship practices. Not all pesticides (organic and conventional) have negative effects for bees, and for those that do there are label directions on how to apply them to minimize the effect on bees (apply when the plant is not in flower or when the bees aren’t active in the evening, etc.)

And ditto Linda’s comments on biodynamics – not supported by science and often a label used to make people think they’re doing something “in tune when nature” when most of it is malarkey.

What a tour de force and as a no dig gardener I heartily agree with most of it!

It does surprise me the large depths of mulch you use your side of the pond but I am sure it works very well to eventually add a huge amount off organic matter.

As to controlling weeds, I never read about ground elder, couch, bindweed and such in your gardens. Covering these with a mulch without killing them with herbicide first (or other methods for those who disapprove) seems to me a recipe for disaster.

Roger, in terms of weed control, we’ve been using the deep mulch method successfully for a number of years on many annual and perennial weeds. We published on the method in 2005.

I followed your link back. I am not surprised coarse ground cover would grow very well in all that mulch and might outgrow weeds in the early years. Such a thick mulch would probably suppress grass but not the bindweed and aegopodium i quoted which I believe would have a field day!

Surprised you mowed back before treating with glyphosate although I would still expect it to work against intact grass plants.

Of course the weeds I quote would not be killed by one spray and in the case of ground elder you would not be completely rid of it for at least two years.

I want to be rid of ALL perennial weeds before planting my herbaceous borders and delicate mixed plantings

The mowing reduces resources to the plant by removing most of the photosynthetic tissue. That makes it harder to recover from mulching.

Soil, mulch, lumber… that adds really fast, it makes sense only for a tiny feel good garden, an elitist garden so to speak. If you are not an independently wealthy person who wants to garden as to produce a good chunk of the food you eat raised beds plainly make no economic sense. I see people investing an arm and leg in the raised beds just to abandon it all for good. High costs and efforts, low production kill enthusiasm fast.

I see a lot of raised beds abandoned. But each bed (that I see) represents another urban dweller that made an effort to understand what it takes to make food grow. Usually it is busy lives and the lack of knowledgeable garden babysitters when people travel that forces abandonment. The fact that the bed was not in the ground is because the soil beneath in the tiny urban plot was nothing but rock or caliche.

I live in Nebraska. I have both raised beds and an area we currently till in our vegetable garden. The no till method intrigues me. How could the no till method be used to raise a home crop of sweet corn? We also grow a lot of tomatoes in our crop rotation. How could diseases be prevented if they are planted in the same space as mentioned by the article you sourced (Yield of Dreams)?

Thank you for your time

I would suggest planting your corn in side by side wide beds (at least 4′ with 2′ space between). You can do the individual beds like the no till method I describe where you put several inches of new soil/compost on top of the native soil. You’ll want to do a bigger bloc than just a single bed, since corn is wind pollinated and the pollen basically doesn’t move far (In farm fields the first few feet into the field has relatively low yield). You may even want to assist pollination by removing the tassle from the top and shaking them on the silks once the silks appear, especially if you can’t plant in a wide block.

As for disease and crop rotation. We suggest a 4 year rotation, meaning that what you plant this year shouldn’t be back in that spot until 5 years from now. Corn and tomatoes have few common pests, so they can be part of that rotation period in the same space. For best results, find two other crops/crop families to grow in the same space the other two years.

I live in CO where we have pocket gophers that will eat the roots of my vegetables if they are grown in the ground. We line the bottom of the raised beds with hardware cloth wire to keep them out.

Organic vegetables are sprayed??! Not mine!

You mention the PNW lumber industry. Yes there are some well-managed lumber farms, but as someone who has watched weyerhauser and other companies demolish our beautiful mountains, I can say that the logging industry is absolutely devastating to our local environment. They technically own large swathes of these mountains that they ‘allow’ the public on, but a lot of it is old growth rainforest being reduced to a patchwork of immature trees. I can’t tell you the heartbreak of going out to one of my favorite woodland spots to find it had been practically clear cut since the last time I visited.

So in conclusion, if you have the ability, use recycled or reclaimed wood in your raised beds. Often it’s possible to find non-chemically treated pallets for free, or reusing some wood from old shelves or something. Not everyone has access to these types of things, but if you do please consider not using fresh lumber.

I have raised beds for one reason only gophers!!