My social media administrator (aka cat herder extraordinaire) reminded me recently that I’d written a post on xylem function and promised to follow up the next month with a post on how phloem works. Well, that was about 18 months ago. Guess I better keep my promise.

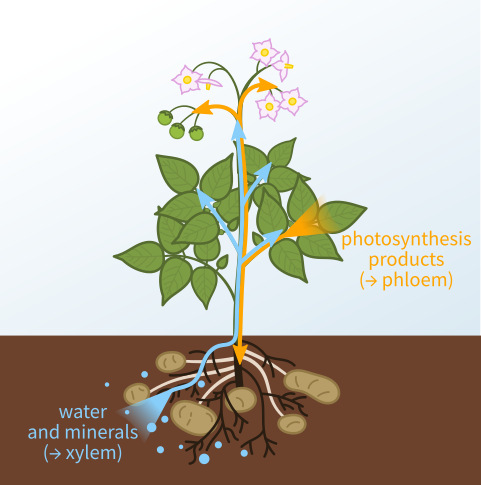

Do read the linked post if you don’t remember why “xylem sucks.” In contrast to xylem, functional phloem is an interconnected series of living cells with cell membranes. The presence of a membrane means the plant can regulate what goes in and out of the phloem, and the direction of phloem flow is determined by the relative concentrations of dissolved substances in the water – most importantly sugars derived from photosynthesis. Areas of high sugar concentration are sources; areas of low sugar concentration are called sinks. As these words suggest, phloem contents are moved from the source to the sink. This process is called translocation.

The most obvious sources in plants are leaves and other green tissues: this is where photosynthesis takes place and sugars are created. Other less obvious sources are woody roots, trunks, and branches: carbohydrate reserves are built up in the fall, as winter-hardy species enter dormancy and deciduous plants shed their leaves. Carbohydrates are re-mobilized in the spring when trees, shrubs, and perennials emerge from dormancy.

Like source tissues, sink tissues vary with the season but can also change daily – especially during the growing season. Expanding leaf and flower buds demand energy for building new cells; ripening fruits require large quantities of sugars. As new branches grow and produce leaves, their demand for carbohydrates decreases until they become source tissues. Translocation is a complex, dynamic process, where phloem in different parts of the plant translocate sugars in different directions.

This information can be used to guide your gardening practices:

Application of translocated herbicides. While we always want to reserve chemical weed control as a last resort, sometimes it’s necessary when other methods aren’t successful. Glyphosate (the active ingredient in Roundup) is applied to leaves and is carried through the phloem to sink tissues. When you read the label on a glyphosate-containing herbicide, it will mention that late summer/fall application is needed to kill the roots of perennial weeds. Consider hedge bindweed (Calystegia sepium), a pernicious and difficult weed to remove by mechanical or cultural means once it’s established in a garden or landscape. Glyphosate will successfully kill this weed but only if it’s applied after flowering. At that point the plant is no longer putting resources into either flower production or vegetative growth; instead, translocation moves carbohydrates (and the glyphosate) to the roots for storage over the winter. Killing the underground storage tissues means this herbaceous perennial will not reappear the next spring.

Pruning the crown during the growing season. When plants are actively producing new leaves and flowers, translocation is generally directed towards these tissues. Pruning leaf-bearing branches and stems has two consequences: removal of source tissues (the leaves) and increased demand for resources from the rest of the plant. Carbohydrates are moved from other sources, like remaining leaves and woody storage tissues, to the expanding stem and leaf buds that have been stimulated by pruning. This is why chronic and/or severe pruning can have a dwarfing effect on woody plants: woody storage tissues are depleted of their resources which are translocated to the developing buds. Until the new growth leafs out, it will remain a sink tissue.

Pruning the crown after transplanting. Take the information from the previous section and now consider the additional sink that has been created during transplanting. Successful establishment of a newly installed plant requires rapid development of new root tissues. Pruning the crown of new transplants siphons much of the stored resources away from the roots, reducing the rate of root growth and establishment. Reduced root establishment also means reduced uptake of water, which will damage the newly expanding buds and leaves. Bottom line: do NOT crown prune after transplanting, except to remove diseased, damaged, or dead branches. Wait until the following year to undertake any structural pruning.