Most of us have witnessed dicot seed germination at some point in our lives – watching the coytledons transform from seed halves to green, photosynthetic structures, while the radicle developed into the seedling root system. This seedling root – or taproot – is important to seedling survival as it buries itself in the soil to provide structural support and to give rise to fine roots for water and nutrient absorption. But that’s where much of our visual experience ends – because we don’t see what’s happening underground. Without additional visual information we imagine the taproot to continue growing deep into the soil. And while this perception is borne out when we pull up carrots, dandelions, and other plants without woody root systems, the fact is that woody plants do not have persistent taproots – they are strictly juvenile structures. Understanding the reality of woody root systems is critical in learning how to protect and encourage their growth and establishment.

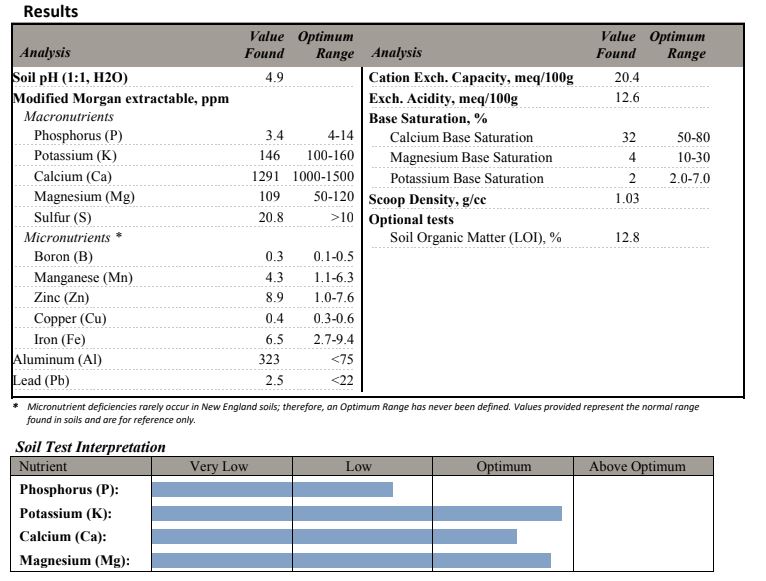

Trees, shrubs, and other woody perennials all have juvenile taproots just like their herbaceous counterparts. But these long-lived plants develop different morphologies over time, which are primarily determined by their soil environment. Water, nutrients, and oxygen are all requirements for sustained root growth. Gardeners always remember the first two of these needs, but often forget the third. And it’s oxygen availability that often has the biggest effect on how deeply root systems can grow.

Whole-plant physiologists have known for a long time that “roots grow where they can” (Plant Physiology, Salisbury and Ross, 1992). But this knowledge has become less shared over time, as whole-plant physiologists at universities have been largely replaced by those who focus on cellular, molecular, and genetic influences (and can bring in large grants to support their institution). Sadly, many of these researchers seem to have little understanding about how whole plants function. Simply looking at the current standard plant physiology textbook (Plant Physiology and Development, Taiz et al., 2014) reveals as much. (To be fair, there is now a stripped-down version of this text called Fundamentals of Plant Physiology, [Taiz et al., 2018] but even this text has little to do with whole plants in their natural environment.) If academics don’t understand how plants function in their environment, their students won’t learn either.

Well. Time to move on from my soapbox moment on the state of higher education.

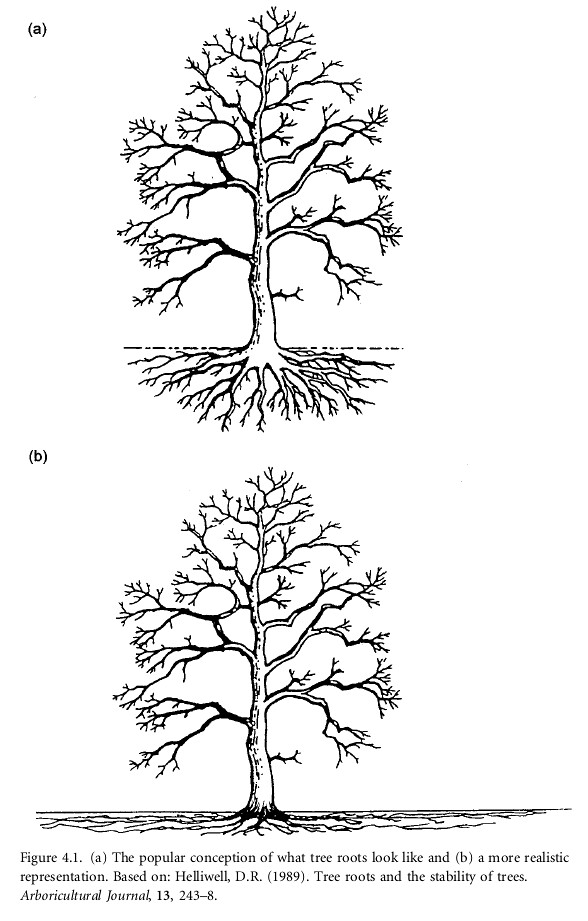

Let’s look at what happens with a young tree as it develops. The taproot grows as deeply as it can, but eventually runs out of oxygen so vertical growth stops. At the same time, lateral root growth increases, because the levels of oxygen closer to the soil surface are higher. These lateral roots, and their associated fine roots, develop into the adult root system, continuing to grow outwards like spokes on a wheel. When pockets of oxygen are found, roots dive down to exploit resources. These are called sinker roots and they can help stabilize trees as well as contribute to water and nutrient uptake.

Gardeners and others who work with trees and other woody species would do well to remember that woody root systems, by and large, resemble pancakes rather than carrots. These pancakes can extend far beyond the diameter of the crown – so this means protecting the soils outside as well as inside the dripline.