When you talk about killer plants, your mind may conjure images of a man-eating plant in “Little Shop of Horrors,” insect-eating Venus flytraps or poisonous plants like deadly nightshade.

While all of those scenarios are interesting in and of themselves, what about plants that attack other plants?

I’m talking, of course, about parasitic plants. These plants thrive on stealing nutrients from other plants, either weakening them or, quite possibly, killing them.

Parasitic plants connect themselves to a host plant and siphon off the sugars that plant produces and the nutrients it pulls from the soil. These plants often bend the definition we have in our heads of plants, since they don’t have to behave like other plants that make their own food.

Probably the most well-known (and beloved) parasitic plant is mistletoe. The plant that gives us the warm fuzzies and romantic feelings around the holidays makes its living by feeding off of the trees in which it lives. They don’t talk about that aspect of the plant in all those Christmas songs. It doesn’t kill the tree, but a heavy infestation can weaken a tree and slow its growth.

While they are few in number, there are some parasitic plants you may run into. Another parasitic plant in our part of the world is the Indian pipe (Monotropa uniflora), a white, chlorophyll-free plant that resembles a smoking pipe as it unfurls from the forest floor. Without chlorophyll, it can’t make its own food, so it connects itself to a nearby tree (usually beech) for nutrients.

Another plant, called a beech drop (Epifagus americana), also makes its living in the same manner. A plant called squaw root or bear corn (Conopholis americana), because it resembles an ear of corn growing out of the forest floor, is a parasitic plant that connects with the roots of oak trees.

These plants may cause a little damage to their host plants. This week, though, there seems to be something more sinister afoot. I received two different calls about the same parasitic plant this week, from different parts of West Virginia (one of which came from Ann Berry, associate vice president for marketing and outreach at WVU). It seems that the problem here was with a parasitic plant called dodder (Cuscuta sp.). Despite the name, I assure you that this plant does not dodder around when it comes to feeding off other plants. This plant can severely infect and potentially kill any plant it touches.

Seeds of the plant germinate in the soil, so it starts life just like any other plant. Once germinated, though, the seedling has about 10 days to find a host plant to attach to and begin feeding. But this is not left to chance — it seems that dodder is a pretty good hunter. Scientists have determined that dodder can, in a way, sense chemical signals from nearby plants and grow directly toward them.

Dodder is an odd-looking plant, and many people don’t even know to classify it as a plant. It grows in long strings, often without leaves (or only having inconspicuous ones). Different species can be different colors. The one that is most common here is often a yellow-orange color.

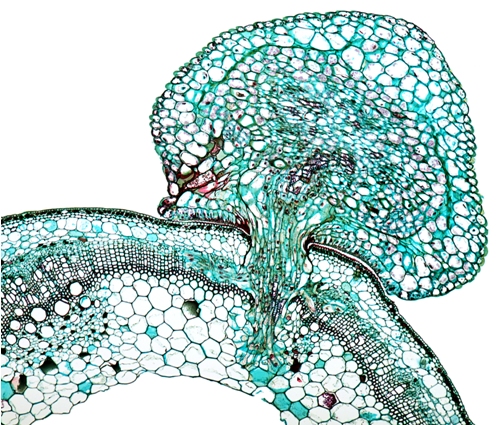

Once the dodder touches the soft tissue of a plant (leaves or stems), it inserts a structure called a haustorium into the plant. Haustoria insert themselves into the plants vascular tissue (veins) and siphons off the water, sugars and nutrients. After the connection is made, the dodder plant detaches its roots from the ground and becomes completely reliant upon the host plant. Luckily it has trouble attacking woody plants, so it mainly goes after herbaceous ones.

One connection is bad enough, but the dodder twines its way around the plant as it grows, resembling what some would call “silly string.” Everywhere the dodder touches the host, it sends in new haustoria to strengthen its connection. If other plants are close enough, the dodder will grow outward through the air to ensnare another host. It can easily grow to encompass many plants, covering them completely and eventually strangling them or starving them out.

My advice to both of the callers this week was to remove as much of the plant as possible, as soon as possible. Unfortunately, the plant can regrow from the connections it makes with the host plant, so you often need to remove whole parts of the plant or the whole plant itself. If it has only made one or two connections, you may be able to control it just by removing the dodder from the plant.

Dodder is hard to see on the ground as it germinates, so it is only usually spotted after it has attached and grown on a plant. If you do happen to catch it before it attaches to a plant, cultivating the soil to break it up and removing as much by hand as possible will help. Unfortunately, there is no spray or control method that will kill the dodder without killing the host.

Dodder is definitely a bizarre plant that many have not seen. Keep an eye out for it this year, since it seems to be cropping up in unexpected places. It just goes to show you that sometimes it’s a plant-eat-plant world out there.

This article was originally published 08.09.15 in the Charleston Gazette-Mail. You can find more article at wvgardenguru.com.