By Charlie Rohwer (Visiting Professor)

The recent assassination attempt England, interesting and significant geopolitically, has reminded me about one of my favorite Latin plant names. A report on the radio stated that atropine therapy is used to treat the specific poison involved in the attempt. To paraphrase Dr. Randy Pausch, “I’m a doctor, but not the kind who helps people.” Therefore, I have no authority on the medical uses of atropine. The world Health Organization lists it as a preoperative anesthetic on its list of essential medicines, so it must be pretty important.

But I do like horticulture and I like words. That’s where my interests lie in relation to this story. Many medicines are or have been plant-based. Atropine itself comes from certain plants in the nightshade family. Like any chemical people use, dosage of atropine determines its effects; atropine can be medically useful, or it can be deadly. The drug is named after a specific plant from which atropine can be obtained, Atropa belladonna. The omnibotanist Linnaeus named it in 1753 (can someone come up with a better word for him than ‘omnibotanist?’).

‘Belladonna,’ as it’s commonly called, is a small shrub native to Europe and Asia. ‘Belladonna’ comes from the Italian words ‘bella’ and ‘donna,’ meaning ‘beautiful woman.’ An extract from the plant was applied topically to eyes during the Renaissance to dilate pupils. One sign of sexual arousal is dilated pupils, so the extract would cause a response that looked like sexual arousal. If you were a lady going to a fancy party during the Renaissance and you wanted to look beautiful, belladonna may have helped (according to beauty standards of the time). My optometrist told me atropine isn’t used for retinal exams today because its effects last too long.

The other common name for Atropa belladonna is ‘deadly nightshade.’ The drug, atropine, is made of two isomers of hyoscyamine, made by the plant (and some other related plants). At some doses, hyoscyamine causes muscles to relax (like the iris, for example) due to its effects on nerves that control muscles. At larger doses, it can kill because you need muscles to breathe and to pump blood at a reasonable rate. Dosage and route of entry are important!

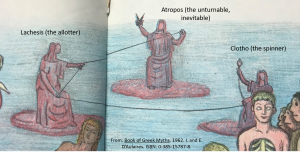

So Atropa belladonna was used to make ladies beautiful, hence the epithet ‘belladonna.’ But what about ‘Atropa?’ What’s that mean? Where does the drug atropine ultimately get its name? My favorite book as a kid was “D’Aulaires’ Book of Greek Myths.” Linneaus borrowed from the Greek myth of the three Fates in order to name deadly nightshade. According to D’Aulaires, these goddesses of destiny “…knew the past and the future, and even Zeus had no power to sway their decisions.” Nobody can escape fate. The three fates were named Clotho, Lachesis, and Atropos. The fates are responsible for the thread of everybody’s life. Clotho spins the thread at birth, Lachesis measures it out and determines destiny (what’s on the thread and how long it is), and Atropos (‘inflexible’ or ‘unturnable’) cuts the thread after Lachesis has apportioned it. Atropos is the goddess directly responsible for the end of everyone’s thread of life, and her action is final.

Atropa belladonna simultaneously means something like ‘inevitable, inflexible death’ AND ‘beautiful lady.’ Indeed, the dose makes the poison.

Love it, Dr. Rohwer. I don’t know if you follow the blog Nature’s Poisons by forensic toxicologist Dr. Justin Brower, but here’s his entry on Atropa belladonna …

Here’s a great, more detailed take on the history of the plant and uses of atropine, including tales of witches, Bacchanalia, and attempted murder using gin and tonic. Atropine poisoning symptoms: “Hot as a hare, blind as a bat, dry as a bone, red as beet

and mad as a hen.”

Lee, MR. 2007. J R Coll Physicians Edin. 37:77–84.