If you follow national news, you may have noticed that Sudden Oak Death disease caused by Phytophthora ramorum has been found again in a new state and has escaped into retail commerce and thus into gardens. This is news because the disease is a killer of rhododendron, oak, camellia and many other ornamental plants. Yesterday I was measuring trees in a research plot here in California and I found that one of my subjects had turned brown and lost all its leaves. On checking, I discovered a Phytophthora collar rot was the cause of the symptoms. Phytophthora diseases kill woody plants, often our cherished specimen plantings. This blog post is to introduce you to Phytophthora collar rots, their diagnosis and treatment.

Phytophthora means plant destroyer in Latin. It is the “deathstar” of plant destroyers and once it has infected, death is the usual outcome. All Phytophthoras are Oomycetes. These are organisms that form an Oospore. Oospores are usually produced when two strains of Phytophthora join and the sexual organs form resulting in this spore. It is thick walled and can live for years in soil without a host. Phytophthora used to be considered a fungus but this was changed some years back to put all Oomycetes in groups that are more closely allied with brown algae. Phytophthoras are not in the kingdom fungi but rather the SAR supergroup of organisms. One main difference between these microbes and fungi is that Phytophthora has cellulose in its cell walls just as plants do. There are hundreds of species of Phytophthora, most affect flowering plants especially woody plants. Very few affect grasses and monocots. There are some that affect palms and others, vegetables and herbacious plants. The late blight fungus Phytophthora infestans caused the Irish Potato famine that resulted in millions of deaths (of people and potatoes) and migration (of people not potatoes) to the United States to avoid starving further. caused the famous Jarrah (a Eucalyptus spp.) die off in Australia, one of the largest known forest epiphytotics. Phytophthora species occur worldwide and affect plants in almost every garden.

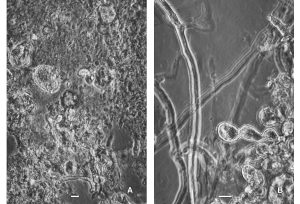

Why are Phytophthoras so successful and how do they get into gardens? I think the answer is that they are cryptic. You can not see any of the spore stages, even with a microscope. There is no “mold-like” growth of the pathogen that you can see either in soils or on the plant. This is because the organism lives inside plant tissues and is very reduced in soils where is survives as spores. Unlike many fungi, you can’t see the mycelium of most Phytophthora species. In plants, Phytophthora usually grows in the vascular cambium of roots or stems and kills those tissues. Plants react to Phytophthora by producing phenols and other phytochemicals turning tissues brown. Brown roots or spreading brown cankers on the main stem are common. When Phytophthora kills the tissues on the main stem this often causes a basal stem canker near the soil line. Usually the plant collapses rapidly with all the leaves turning brown or falling from the plant suddenly. Sometimes basal cankers are associated with deeply planted trees and shrubs or where soil has been added over the root collar. Since basal cankers are under the bark they may not be visible while active and need to be revealed with a knife to expose the brown tissue.

Phytophthora diseases are increased by excess water in soil or on plants. Overly wet situations are predisposing to these diseases if the pathogen is present. Other conditions like reduced oxygen in the rootzone (from compaction), increased salts in soil, very dry conditions followed by very wet circumstances all promote Phytophthora. There are also some groups of plants that seem to be very susceptible—these include: rhododendron, camelia, oaks, cyclamen, most plants in the Ericaceae (madrone, manzanita, blueberry etc.), cedars, pines, and the list goes on. It is hard to avoid susceptible plants because there are so many of them.

Phytophthora species are not native everywhere but have been distributed far and wide by people. Nurseries are prime disseminators of Phytophthora infested plants. Fungicides “subdue” the pathogen but do not eradicate it. So a plant can look healthy while still being infested with Phytophthora. When the fungicide wears off, the plant may become sick if conditions are right for the Phytophthora to grow. Another reason why this type of pathogen is so successful is that a plant can have 50-75% of its roots killed before symptoms begin to show on above ground plant parts. Wilt and collapse only occur very late in the progress of the disease. Because of this, it is important to inspect plants before bringing them home. Never purchase a plant with brown feeder roots, or this could be the starting point for Phytophthora in your garden.

If you are an avid gardener who likes to try new plants all the time, then your future encounter with Phytophthora is likely inevitable. You can do things to limit its development.

-Plant on berms or mounds while avoiding planting in low or poorly drained places

-Use wood chip mulches from freshly chopped tree parts

-Add gypsum to soils as part of your mulching protocol

-If you irrigate your garden allow drying out periods between irrigations

-Plant “high” so that the root crown is clearly exposed

-Do not volcano mulch or cover the root crown with anything at all

-Avoid planting woody perennials in turfgrasses or lawns

Fresh wood chips are often broken down by fungi that release cellulase, this enzyme is toxic to all Phytophthora’s, and the reason why FRESH mulches are so important to create soils with cellulytic enzymes that destroy this pathogen. As gypsum dissolves it provides a slow release source of calcium ions which are also toxic to the swimming spores of Phytophthora. While fungicides can also help limit Phytophthora development, the cultural practices listed above will be just as important in preventing and limiting root and crown rot disease in your garden.

Yet another reason using those valuable fresh arborist chips!

Good advice on that list. I would add deep aeration near the trunk to speed drainage, and replacing soil there with pervious aggregate to enable drying.

Mulches from Salix and rosaceous species are proven fungistatic; see Percival’s work.

I don’t understand “Add gypsum to soils as part of your mulching protocol”. 1. How is soil amending part of mulching? 2. How does this jibe with previous GP dicta against soil amendments?

Plus, gypsum is controversial; wording in A300 was changed to discourage some claims about its use, yet the dominant A300 company still sells it (600# on one tree, for instance).

I did not see in the article–how would gypsum resist Phytophthora?