As many parts of the US face drought or dryer than normal conditions and issues about water availability especially in the western states, many gardeners are reassessing their relationships with plants and irrigation. Many gardeners, especially in the west, are replacing their lawns and landscape plants with more drought and dry-weather tolerant options. But there still are times when irrigation might still be necessary, e.g., growing vegetables and fruits, establishing new plants, and more. Using water efficiently and effectively is key in these situations even when water is available and drought conditions aren’t as prevalent. Efficient water use and good irrigation can also mean a savings on the water bill AND a reduction in plant diseases spread by water application on the leaves. Paired with mulching, efficient irrigation can drastically reduce the amount of water used in gardens and landscapes.

In order to make the best choices for your garden, I’m going to talk through some of the most and least efficient irrigation methods for your gardens and landscapes. I’ll be starting with the most efficient methods and working my way to the least.

Drip Irrigation

Drip irrigation is considered one of the most efficient methods of irrigation because it applies water directly to the soil at the base of the plant and therefore typically uses the smallest volume of water. Research shows that drip irrigations have around a 90% efficiency rate. . Most systems sit above the ground and apply water to the soil surface, but some sub-soil systems are available. The system usually involves a filter and pressure regulator to keep the emitters functioning and applying water at the proper volume.

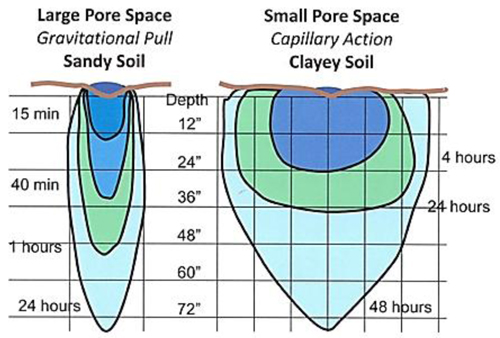

The efficiency of drip irrigation comes with a caveat though. When applied to sandy or rocky soils, water from drip irrigation has a much smaller spread laterally in the soil due to less capillary action and higher gravitational pull due to the large pore spaces. This means that there isn’t as much coverage of water in the root zone. In order to combat this drip emitters must be closer together or have a high flow rate, both of which increase water usage and reduce the effectiveness of drip irrigation in sandy soils. Read more here

There are typically two types of application methods: tubes or tape that have pre-made emitter holes at set distances that disperse a set amount of water per hour or emitters that are inserted into the end of solid tubes (that may or may not have an adjustable flow rate). The tubes and tapes that have holes pre-made are typically used in vegetable gardens, row crops, or in beds where plants are uniformly planted. Systems with the inserted emitters are often used in landscape settings where it makes sense to water individual plants, such as trees, shrubs, or large perennials.

Given the low volume of water disbursed by the system, water pressure is regulated in a way that ensures even distribution as long as it isn’t modified than from the manufacturer or factory specs.

For information on installation and maintenance, check out these resources:

Drip Irrigation for Home Gardens – Colorado State Univ. Extension

Irrigation Video Series – Oklahoma State Extension

Microsprinklers

Microsprinklers function on the same type of system as drip irrigation and can sometimes even be combined with drip systems. Instead of small openings that drip water on a small area on the soil, microsprinklers spray a small volume of water over a set radius. The sprinkler heads are typically only a few inches above the soil and therefore apply the water at the base of the plants. Some systems allow you to switch out sprinkler heads that spray in different patterns and distances. One such system that I’ve used has sprinkler heads for patterns from 90 to 360 degrees and from one foot to ten feet in diameter.

While not as efficient as drip, microsprinklers are more efficient than other systems due to low water volume and consistent pressure throughout the system. They can be more flexible than drip irrigation in settings like landscape beds and around trees and shrubs since one emitter can water a larger area with less tubing and fewer parts.

Soaker hoses

Soaker hoses are popular because they are plug-and-play. You can just attach them to your faucet and don’t have to worry about cutting and assembling tubing and parts. Water is released through the surface of the entire hose, making water application much less precise that drip and microsprinklers as well. Keep in mind that soaker hoses don’t have pressure regulation like drip and microsprinkler systems do so you’ll often find inconsistent watering when you use them. More water leaves the soaker hose at the end closest to the faucet and less (or none) at the far end. The result is usually excess water in some parts of the garden and not enough in others.

Soaker hoses also release a much higher volume of water than drip and microsprinkler systems, which can result in overwatering and water waste. I learned this from experience when I accidentally left a soaker hose running for about three days. The garden was nicely flooded and the water and sewer bill topped out at over $500 that month.

Sprinklers

Sprinklers are probably the most common irrigation system used because of their simplicity. Home gardeners might use the hose-end individual sprinklers purchased at the garden shop which can quickly water a large area. And many homeowners, especially in areas where there isn’t rainfall sufficient to support grass growth, have sprinkler systems installed in their lawns. However, sprinkler systems are only around 65-75% efficient. Spraying water in to the air, especially on hot and dry days, reduces efficiency through evaporative loss. Sprinklers are also less precise in where you can aim and apply water. There’s also the added issue that overhead application of water can lead to or worsen plant disease issues by making conditions favorable for the spread and growth of fungi and bacteria. If possible, use sprinklers only on a temporary basis like establishing new plants or make sure they are calibrated effectively.

Hand watering

While hand watering probably uses a smaller volume of water than sprinklers and you can direct water more precisely, there are still issues with evaporation and overhead watering. In addition, hand watering is usually less effective than other methods because humans are impatient and actually don’t water long enough. Most plants will benefit from a long, deep watering but many gardeners will only give a pass or two with a water hose and will underwater plants. This can cause roots to accumulate in the upper layer of the soil and increase long-term water needs of the plant. Rely on hand watering for temporary needs like plant establishment or container plants (though you can use drip and microsprinklers in containers as well) and use a more efficient strategy long term.

Wrapping it up

There are a number of ways you can manage the water needs of your landscape, from renovating your landscape with more water efficient plants to making more efficient use of water through effective and efficient irrigation systems. As more and more cities and states across the US place restrictions on water use having several irrigation tools in your toolbox will be helpful. Always remember that the best strategy is to grow plants suited to your environment to reduce water use in the garden. And in places where there isn’t sufficient water for grass to consider removing lawn and replacing with native vegetation and xeriscaping. Irrigation systems can help in areas with unexpected drought or weather issues but for long-term sustainability gardeners in drier climates should adapt their properties where they live.

Other Sources

I try to keep everything I can out of the dump and minimize the use of plastics. I use a very expensive rubber hose (that I have now had since 1996, so it was worth every penny). I use a fan shaped waterer with a valve that mimics a good rain shower (without the impact of a downpour).

While I agree that many gardeners are impatient, I think most have never properly learned to water by hand. Watering is something that should only be symptomatic or based on past experiences of weather and the plants species’ response to it.

This is a contemplative and mindful practice that involves looking carefully at the plants. After all, isn’t that why you put them in? To spend some relaxing time enjoying them? This is the big chance. It is a time to breathe in, to notice problems at the earliest possible moment, and maybe even reflect on just how important plants are…they support us in every possible way…putting a car in space as a stunt was silly…it should have been a greenhouse! Knowing them better is utterly worth our time and effort.

Water newly planted plants, plants in pots, and plants showing distress (which first should be examined to determine if lack of water is actually the cause). Use the valve to avoid watering plants that don’t need it. There is no watering system that can replace the keen eye of a caring gardener. The garden will ALWAYS only be as good as the gardener.

This is a great summary of different methods but also highlights our reliance on plastic. Both of the most effecient methods are probably only economical due to how cheap plastic is. Which is also unfortunate because in my experience drip systems can develop leak issues fairly early on and people I’ve known replace them every couple of years.

It would be interesting to see a variation on this psor covering alternatives that night use more sustainable materials. While on a smaller scale I believe there’s a practice of burying terracotta jugs to slowly release water.

Another excellent article, especially with your great discussion on drip irrigation.

Here in Orange County, CA we have mostly sandy loam soil, usually with a shallow clay layer 4″ to 12″ deep where drip irrigation soaks in quickly and pools at the clay layer. Shallow root ground cover does not do well with this, but deep rooted shrubs and trees love it. With the movement to more climate appropriate landscape here in Southern California, the change to drip irrigation is common choice without considering the cons of drip on sandy loam. Getting the landscape and irrigation system wrong the first time is very common here.

As an amateur trying to learn landscape irrigation mostly through experimenting at home and making lots of errors, and as a Landscape Committee member that helps supervise professionals maintaining 32 acres of our community green areas, I can attest to the pros getting it wrong often. Irrigation efficiency is commonly misunderstood and yet can have a huge impact on saving water if it is optimized.

Sprinklers have evolved a great deal in recent years and may deserve a second look. I have found that rotator head sprayers with pressure regulated bodies may be the best option for turf and shallow-rooted ground cover in sandy soil. (Such as the Hunter MP rotator and others.) These sprinklers make it easy to engineer a system with very good coverage and the water being applied at a slower rate than rotating heads or other sprayers, greatly reducing runoff and efficiency. Unfortunately, these heads are only available for a radius greater than 5′ at this time as far as I know. These sprinkler heads spray multiple rotating streams at different angles for good coverage and have adjustable spreads. A 90° spread will apply the same water density as a 360° spread. You can also choose higher flow rate heads to adjust for shade vs full sun in the same zone. Setting the irrigation controller properly has greatly reduced my water use in the areas where I am currently using these on turf. I was not able to achieve this high an efficiency with any other automated means.

Thanks for your feedback and info. Things are indeed evolving all the time. The info about those sprinklers is interesting. Thanks for sharing!