Ok, ‘Hot’ might not be exactly the right word, but winter in the Midwest has certainly been warmer than average this year. I did a little trolling around on Michigan State University’s Automated Weather Network website, which has been logging temperatures and other weather variables around the state for the past 15 years and compared our current winter here in East Lansing to recent years. Since the middle of December our average daily temperatures are 5.2 deg. F above the previous 15-year mean. The departure from the 15-year mean is even greater (+5.6 deg. F) when we look at minimum temperatures.

15-year average Minimum daily temperature and Current-winter daily minimum for East Lansing, MI.

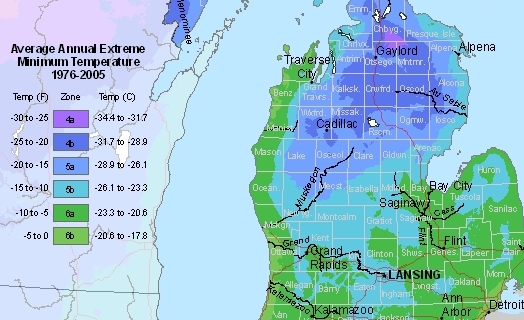

Minimum temperatures are especially important when discussing winter injury to landscape plants since extreme low temps (and the conditions immediately preceding them) are often responsible for many of our winter injury problems. With a generally mild winter and only a few, brief temperature dips below average, one might expect that we will see few winter-related plant problems this spring. However, prolonged exposure to temperatures above average means that plants are beginning to deharden early. We see several signs of this already; such as witch-hazels blooming in protected locations and sap in maple trees running 2-3 weeks ahead of normal http://www.michiganradio.org/post/michigan-maple-syrup-producers-say-season-extra-early-year

February 28, 2012. Witch-hazel in bloom on MSU campus.

While other trees and shrubs may not provide the same outward signs, they are progressively becoming less cold-hardy by the day. Unfortunately, temperatures, like the stock market, rarely move in a straight line. Here in mid-Michigan, temperatures in the single digits are possible throughout the month of March. Given the preceding mild conditions, a sudden, severe cold snap still holds the potential to cause considerable damage to developing buds on trees and shrubs. This type of late from damage may be evidenced by shoot die-back, bud-kill or death of newly-emerging shoots. As always with winter injury, the final result won’t be known until late May or early June.