One of the questions that arise in discussing native plants is the question of whether ornamental cultivars (e.g., ‘October golory’ red maple) can or should be considered ‘native’. In short, my answer is ‘No.’

Here’s my rationale on this. First, when we think about natives we need to put political boundaries out of minds and think about ecosystems. Political boundaries – a ‘Michigan native’ or ‘an Oregon native’ – are meaningless in a biological context. What’s important is what ecosystem the plant occurs in naturally. In addition to taking an ecological approach to defining natives we also need to consider its seed source or geographic origin. Why is it important to consider seed origin or ‘provenance’? Species that occur over broad geographic areas or even across relatively small areas with diverse environments can show tremendous amounts of intra-species variation. Sticking with red maple as an example, we know that red maples from the southern end of the range are different from the northern end of the range. How are they different? Lots of ways; growth rate, frost hardiness, drought tolerance, date of bud break and bud set. Provenances can even vary in insect and disease resistance.

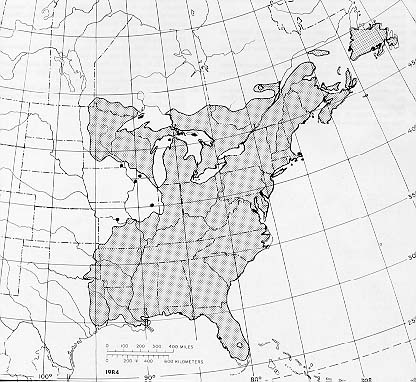

Native range of red maple

If we’re dealing with an ornamental cultivar, do we know the original seed source or provenance? Sometimes yes, sometimes no, sometimes maybe. Think for a minute how most ornamental cultivars come to be. Some are developed through intentional crosses in breeding programs. The breeder may or may not know the geographic origins of the plants with which they are working. Or they may produce interspecfic hybrids of species that would not cross in nature. Some cultivars are identified by chance selection; an alert plantsperson finds a tree with an interesting trait (great fall color) in the woods or at an arboretum. They collect scion wood, propagate the trees and try them out to see if they are true to type. If the original find was in a native woodlot and the plantsperson kept some records, we may know the seed source. If the tree was discovered in a secondary location, such as an arboretum, it may not be possible to know the origin.

So, if a breeder works with trees of known origin or a plantsperson develops a cultivar from a chance find in a known location AND the plants are planted back in a similar ecosystem in that geographic area, we can consider them native, right? As Lee Corso would say, “Not so fast, my friend.” We still need to consider that matter of propagation. Most tree and shrub cultivars are partly or entirely clonal. Cultivars that are produced from rooting cuttings; for example, many arborvitae, are entirely clonal. Cultivars that are produced by grafting, like most shade trees, are clonal from the graft union up. The absolute genetic uniformity that comes from clonal material is great for maintaining the ornamental trait of interest but does next to nothing to promote genetic diversity within the species. From my ultra-conservative, highly forestry-centric perspective, the only way to consider a plant truly native, it needs to be propagated from seed and planted in an ecosystem in the geographic region from which it evolved. Few, if any, cultivars can meet that test.

It depends on the context. If you are trying to persuade homeowners to use more native plants in their landscape planning, ‘

620

improved’ cultivars can be a good thing. If you are trying to restore an endangered ecosystem, it can be bad.

I agree with VG. For instance, dwarf cultivars of some native plants might be more appropriate for small urban landscapes, yet still fill the same ecological function as the wild species. The “brand” of native is often important to homeowners.

Another good use of cultivars of natives expands on VG’s comment. Using native cultivars as foundation plantings or other ornamental plantings around houses (or other buildings such as nature centers etc) to help tie the living space to native areas around the property. For someone living on/near a wooded lot, planting ‘October Glory’ Red Maple would make much more sense than ‘Royal Red’ Norway Maple. This is a large gray area to deal with that can be debated for years. Using a clonal cultivar on a site 1 mile away from where that cultivar was selected makes more sense than using seed with a providence from 100 miles away if we’re talking about 1 or 2 accent plants. Next: how locally ecotypic do you get? In the case of a species with low genetic diversity in a given area (such as Carpinus caroliniana in WI) is there anything wrong with introducing genes from IL, MN, IA, MI to improve genetic diversity? If I keep going this comment will be longer than the original post…

I find it hard to argue with Bert’s reasoning and the comments that follow illustrate how, why and when it might be appropriate to use a “native” cultivar but don’t refute the reasoning. Part of the gardening public is becoming so enamored with the concept of natives that I think they are grasping at straws to to asuage their belief in ecological principal. In my opinion, many want to have their cake and eat it too.

In my own mind, I catergorize some plants as near-natives. These include cultivars of true regional or ecosystem natives and those plants that have become so widely acclimated in a region and have filled or created a long time ecological niche.

Examples might include mullein, Queen Annes lace, teasel, and maybe even Japanese honey suckle here in the mid-Atlantic region.

Japanese Honeysuckle a “near-native” that “has filled or created a long time ecological niche”? It is a horribly invasive and disruptive species to the native Mid-Atlantic ecosystem that literally strangles native species to death. Try again.

I am not arguing against the use of cultivars (I’ve got them all over my place). But we need to recognize them for what they are. I would argue that ‘Native cultivar’ is an oxymoron for the reasons I’ve outlined. Often we don’t know the seed source and through clonal propgation we reduce or elminate genetic variation. Part of ecosystem function is adding vertical structure and complexity, a dwarf cultivar cannot fill the same ecological niche as the species. I think Wes is on the mark with ‘wanting the cake and eating it too.’

“Ornamental” native plant cultivars should be considered native. Contextually an ornamental plant is for ornament, there is little need to consider all of its biological context. Most native ornamental cultivars fulfill their biological purposes as well and do not encroach on the genetic natives. Has anyone seen ‘October Glory’ Maple overtaking or diluting the existing native stands of Acer rubrum? I doubt it. Nativity is not soley for biological purposes, it should consider aesthetic purposes as well. A “sense of place” should be considered when deeming a plant native. I believe an ‘October Glory’ Maple is native regardless of its genetic provenance, it is still Acer rubrum and a native plant. Whether it is planted in PA. or FL. it is still a tree that blends with the native flora and creates an identity resembling that ecoregion. An ecological approach is not the only way to define a plant. It can be defined as a native just as well on ornamental characteristics.

Something I forgot to mention in my comment. I’ve dealt with people rejecting use of a cultivar with providence close to the site they’re working on, but then using plants that aren’t even native to the state. Best example is the use of Echinacea purpurea in prairie restoration in WI. According the the UWSP herbarium it is not naturally found here but restorationists are using it instead of or in conjunction with E. pallida which is state threatened. So not only are they creating habitat for a threatened species and choosing a non-native instead, but they are possibly polluting the gene pool by growing them together. (E. purpurea and E. pallida hybridize readily in gardens) The next thing I’ve always found interesting is that habitat ecologists always assume the worst when it comes to introducing genetic variability from a different providence. Climate is changing, there’s no guarantee that introducing southern genes to northern areas will be a BAD thing. Good genes get introduced as well and resultant offspring could very well be BETTER adapted to the climate, pests, or diseases. Or more suited to use by native species. Or any number of other variables. I’m becoming more of the opinion that we should focus less on providence and more on just getting some more land back to what it should be rather than mowed ditches, right of ways, etc.

I wish I had more time to think about this. Do the bugs that eat “native” trees care if the provenance is FL or NY? It’s not a rhetorical question. I’m reading Tallamy’s Brining Nature Home and am starting to think of “natives” in terms of what wildlife they can support. And Bert, while I’m asking questions, why does your definition of native matter? (I don’t intend that to be nearly as argumentative as it sounds). I get the clonal thing – that’s a reasonable arguement, but what harm comes from Acer rubrum seed collected in Minnesota being grown in Georgia?

Paul, I think part of the answer is in my post under Holly’s entry today. Depending on the species, we can see tremendous variation among provenances in just about any trait you care to mention; growth rate, cold hardiness, drought hardiness, and pest resistance. Along with these there are differences in biochemical make-up, some of which are probably unimportant but some of which could impact interactions with herbivorous insects.

I think it depends on the situation and the plant. A simple mutational variation, such as a pink-flowered Sypmphyotrichum novae-angliae should be considered a “native” because the plant could arise spontaneously in the wild and reproduce to produce a sub-population, or cross-breed back with the standard purple. A double flowered Echinacea purpurea is not, as it cannot reproduce.

The source of tree cultivars is usually someone finding a unique individual in some population or hybridizers crossing some individuals and screening for unique individuals. I feel it is better to use clonal natives than exotics. The only risk would be if so many of hte same clone were planted that there might be a slight dilution in the gene pool. But really folks, how much of a purist can you be. When ignorant landscape archtiects that I know go out looking fo

r natives they sit in the nursery and pick out all the trees with the best form and color. No one selects the “dog” in the batch to preserve genetic diversity. We are a species that leans toward domestication and I agree with so many of the above comments – in wild habitat restoration it is best to use a aa broad selection of seedlings from the region so their offspring are more adapted – but in the landscape, where one tree can fit in one townhouse, asking someone to plant a poorly branches ugly female red maple is going a bait far. We have lots of other problems more important in the landscape – like 50% of the city trees planted dying in the first five years because no one follows planting guidelines or follows up on the trees

Many of the comments are about whether natives or cultivars are best for landscape use. That is not the topic of the opinion piece. To even have that conversation, we need clear meanings of the terms. I agree with the author that cultivars are not native plants. This does not mean that cultivars are worse than native plants, they are simply something else. Not native, not alien.

Has any research been done on comparing the benefits of cultivars vs not cultivars? Like whether or not animals are less likely to use a cultivar?

The basic question here is whether a plant of a given species is more likely to be used by animals if it is propagated by seed or if it is propagated by grafting or rooted cuttings. I don’t know if there have been specific studies on this, but I would be surprised if the answer was anything except ‘It depends’. I suspect it would depend on the particular cultivars used, depend in what type of animal ‘use’ we’re talking about, etc. Some cultivars (e.g., crab apples) may have been selected to produce more fruit than a run-of-the-mill seedling (not that I’m aware of many crabapples that are produced from seed). The thing to remember is that a cultivar is just one genotype of a given species. How is one genotype going to respond relative to seedlings, which will be variable? Impossible to tell. Could be better, worse, or the same.

Was Faribault’s Art Boe’s arborvitae cultivar ‘North Pole’ propagated from seed that evolved from MN?

As a commercial grower and landscaper who has had it up to my eyeballs with ecologist, biologist and other gist in the industry. The fact of the matter is when trying to procure liners for a commercial growing operation the liners are not available locally (in my case New York). The bulk of tree liners come from the Pacific Northwest and some from around the Great Lakes region – not New York. There has been several companies that have tried and failed in New York.

As for landscaping with natives-no-culitvars, I bring in material from Ohio to Maryland to Maine for jobs so even if there are a non-cultivar acer rubrum I may have trucked them hundreds even thousands of miles to job site that would not accept cultivars that were locally grown. I guess all that trucking has no effect on the environment. The best part is some of the growers just lost track of what cultivar they were growing so they just tagged it Red maple and they bought the liners from the pacific northwest and have no idea where the seed originated from.

So on an intellectual level it might be fun to debate the definition of ‘native’ and why they are vastly superior tho their cultivated cousins but the reality is some the natives had significant disease issues that have been significantly improved by cultivars like Ulmus americana, viburnum trilobum, and many more…cultivars are not just to have nice fall colors. As for natives needing less pesticide/fungicide…plant native crataegus near native juniperus virgininia and let me know how that goes.

I would just like the liners sources, the engineers, LA, ecologist, garden centers and landscapers to speak the same language but none of the groups do and there are very few in the industry who truly understands the tree production and commercial availability.